In the middle of the last decade, Washington was anxious in its efforts to restore peace in Afghanistan and at the same time Pakistani power structure was also in the midst of an upheaval. Violence in Afghanistan was on the rise and elite conflict in Pakistani society was becoming more intense with each passing day. Afghanistan needed a stable political base from which it could become a bulwark against the rising tide of new and more ferocious type of Islamic militancy that originally rose in the Middle East but was now shifting its epicenter to Afghanistan. This was only possible—in the perception of most of the regional powers—when more traditional forms of Islamic militancy like Taliban could join hands with the cluster of groups, clans and warlords who were brought to power in Kabul by Washington in the wake of its invasion of Afghanistan.

This international project, which ostensibly had the backing of all the regional powers including Russia, China and Iran plus Washington, was coupled by another regional security project that provided Pakistani military establishment a crucial role in Afghanistan was aimed at preventing ISIS from gaining toehold on Afghan territory.

The three great world powers—United States, Russian Federation and China—have their eyes set on the political, military and security situation inside war-torn Afghanistan. All these great powers have stakes in maintaining peace in Afghanistan so that it would not again become a lawless land and would not again become a safe haven for international terrorists and Islamic fundamentalist groups. For this purpose these powers have initiated two separate projects. The first of these is the peace process in Afghanistan, engaging Afghan Taliban on the one hand and Afghanistan’s government on the other. The second and less publicized but no less significant, project is to eradicate the possibility of rise of Daesh (ISIS) in Afghanistan’s northern, south-eastern and eastern regions. In both the projects Pakistan’s military establishment is playing a leading role.

It was with the help of Pakistan security apparatus that Washington reached an understanding with Afghan Taliban for withdrawing its forces from a war ravaged country. The second international project that Pakistan’s security establishment is leading has the backing of strong regional players including Russia, China and Iran. This project is based on multilateral cooperation among regional states to prevent the rise of ISIS in Afghanistan, which can pose a potential threat to regional countries including Iran, China and Central Asian states—countries which come under Russian Security umbrella. Pakistan hosted a meeting of Intelligence chiefs of Russia, China and Iran to discuss the rising threat of ISIS on Afghanistan’s territory in July 2018. “The conference reached understanding of the importance of coordinated steps to prevent the trickling of IS terrorists from Syria and Iraq to Afghanistan where they would pose risks for neighboring countries,” an official said. The top security and intelligence officials stressed the need for a more active inclusion of regional powers in the efforts to settle the conflict in Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s security establishment is playing a leading role in both of these international projects, a factor which gives the country's establishment much needed confidence and clout to consolidate its hold on power structures in the domestic political scene. It is not only relevant in the international security and political scene, it suddenly finds itself on the right side of great powers, which want it to do a project to consolidate peace in Afghanistan and to contribute in bringing political and security stability to that country.

In the above mentioned two projects, Pakistan has the backing of Washington, Beijing and Moscow, a situation which is in complete contrast with the past when Pakistan—in connection with its projects in Afghanistan—was strictly in American camp and was opposed stanchly by Moscow.

Meanwhile, a former Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif is spearheading a mass awareness campaign to show the leaders of the security establishment in bad light. Nawaz Sharif’s political partners in this campaign come from rural and semi-urban Sindh, religious-political forces from rural and semi-urban Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), and his own political stronghold in the middle-class constituencies of Central Punjab.

These two conflicting trends—enhanced regional security roles for the security establishment and the rise of domestic countervailing political forces, which are opposed to the establishment's oversized role in domestic politics—will determine the status and role of the country's security establishment in the foreseeable future.

The push and pulls of these two conflicting trends will keep the political pot boiling inside the country. Similarly, Pakistan’s security apparatus might have the power to convince Taliban to come to the negotiating table, but this would not guarantee Pakistan’s influence on other political forces of Afghanistan to accept Taliban as a legitimate play in that war ravaged country.

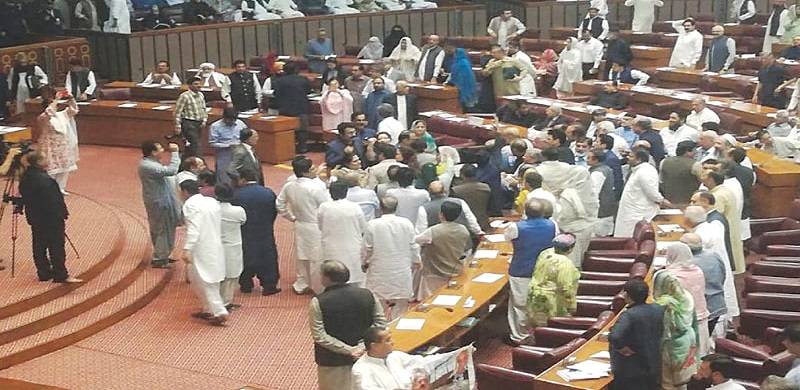

Pakistan’s own domestic political scene shows no signs of settling down in the near future. The architects of present political setup in Pakistan must realise that this setup has a narrow social and political base with only one urban middle class party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), providing support to its edifice. The list of disgruntled forces is long and goes deep into the society. Political engineering at the hands of establishment-linked individuals who have no experience in political dynamics of these societies, are bound to failure.