Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author. Naya Daur does not take any responsibility for the opinions expressed. However, we welcome any counter-argument and offer our platform for a civilised debate.

The oft-quoted couplet of Allama Iqbal – hazāroñ saal nargis apnī be-nūrī pe rotī hai; baḌī mushkil se hotā hai Chaman meñ dīda-var paidā – aptly describes a prodigy like Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi Amrohvi (June 1930–February 1987) who left his indelible imprints in the sphere of art and literature. His large oeuvre speaks volumes about his incredible journey as a painter and poet, which has elevated him to those rare groups of artists who are as much celebrated today as in their lifetimes. In a posthumous acknowledgment of his work, the government of Pakistan has decided to confer on him Nishan-e-Imtiaz on Pakistan Day (23rd March 2021). Previously, he was awarded Tamgha-e-Imtiaz (March 1960), Pride of Performance (March 1962), and Sitara-e-Imtiaz (March 1980) by the Federal Government, although, it is a subject of enormous significance that he never graced the award functions to receive the laurels. These qualities of Sadequain made him one of his kind and earned him the appellation of Faqir (saint).

Sadly, after his death, people started counterfeiting the works of this Faqir. Hinting at the malpractices prevalent in the art-world, famous scriptwriter Anwar Maqsood once exclaimed that Sadequain made more paintings posthumously than when alive; and hence this article aims to unmask certain mala fide activities, including the deceptive sketches of Surah-e-Rahman, which are being carried out globally in the name of this virtuoso – whose death anniversary on 10th February is close on the heels.

It was during the painstaking research that the present writer stumbled upon one San Diego-based organization, Sadequain Foundation USA, which has been, with impunity, producing sham copies of the artist’s portraits. It was founded and run by one Mr. Salman Ahmad who claims to be a legal heir of Sadequain and dismisses allegations against him as unsubstantiated but the facts point to the contrary. He has published about twelve books on the painter such as The Legend of Sadequain, The Saga of Sadequain, and Lines and Drawings by Sadequain which are replete with spurious information and dodgy prints.

It should not come as a surprise to the art-lovers that he supplied deceptive sketches to the renowned calligrapher, Khursheed Alam Gauhar Qalam when the latter was compiling Khatt-e-Sadequain on the rules and principles of Sadequain’s calligraphy. When Mr. Qalam was confronted in this regard he apologetically accepted his ignorance on the matter and vehemently promised on record that he would speak against the supplier. He found himself a prey of deception by those he trusted; he had pledged to bring out a rationalized account of the book wherein he would rectify all the previous inaccuracies but sadly he passed away before the occasion could arise. What is more surprising is that the eminent art scholar and principal of the National College of Arts in Lahore, Mr. Murtaza Jafri testified to the title by writing a prefatory message to it. When Mr. Jafri was communicated to articulate over the topic he politely declined. The strangest part of the narrative is that since 1974, thirty-two original specimens of the Surah-e-Rahman are accessible for public viewing in the gallery of the National School of Public Policy which is in proximity to the National College of Arts. Those were gifted by the illustrator to the school, which is about to name the gallery after him in the upcoming months. One wonders as to how Mr. Jafri could write a laudatory memorandum without consulting the original portraits. It would not be out of place to register that Mr. Salman himself penned a note for the book, thereby confirming that whatever he had supplied to Mr. Qalam were the authentic illustrations.

During the initial interaction of the present writer with Mr. Salman, he appeared very suave and courteous and was ready to furnish all the niceties about Sadequain. Gradually the undercurrents of his conversations became distinct and he got more interested in selling the voluminous tomes he had penned on the illustrator, but somewhere down the line, his aggravation got obvious when he was regularly enquired about certain irrational aspects of the publications about which the present writer had developed doubts.

Beginning with Mr. Salman’s book, The Legend of Sadequain, wherein he writes that the painter had composed four complete versions of Surah-e-Rahman comprising two sets of thirty-one panels and another two of forty panes; but in a Facebook post that he updates later, which contradicts his recorded statement in the text, he asserts that Sadequain had composed only three sets of the aforesaid holy Quranic verses in 1969, 1974 and 1980. Though, in reality, it should be broached here that the visual artist had composed three versions in the years 1970, 1974, and 1981. One might ask as to how he could carve a long array of opuses on Sadequain when he remains ignorant about the years when the authority was creating his awe-inspiring drawings. Such divergent views are extremely recurrent with Mr. Salman and, thus, he could be anyone but a legitimate benefactor of art.

He adds to his post that he had purchased thirty-one phony portraits from one Mr. Ishrat Hussain, whom he calls a scoundrel, of Karachi and he uses such prints to exhibit globally and introduce the Khatt-e-Sadequani i.e. Sadequains’ font. If one goes by his statements he has used such designs in at least twelve exhibitions and three publications on the painter. The question arises as to what drives him to exploit such counterfeit copies which he has already termed deceptive.

Furthermore, he has not published the original impressions of Surah-e-Rahman in his aforementioned tome, neither has he incorporated bona fide specimens in his other texts on Sadequain. Instead what one finds in such compilations are the bogus drawings that his foundation has been churning out since 2007.

If he were a genuine sponsor of the art he would publish the works which are on display at the National School of Public Policy, but he avoided doing since he wanted to showcase the forged paintings for commercial reasons and to sell them.

Despite all the claims by Mr. Salman about his credentials, it is startling to discover that no reputed newspaper of Pakistan has so far reviewed any of his lengthy assortment of works, neither have there been any announcements of the book-launches. He received further backlash when distinguished organizations and galleries such as Anujman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu, Arts Council of Pakistan-Karachi, Frere Hall, Mohatta Palace, Lahore Museum, Alhamra Arts Council, etc. severed ties with him on account of his varied dubious activities. Pakistan National Council of Arts and the State Bank Museum of Pakistan in Karachi, which are studded with lavish murals by Sadequain, have also cut off their associations with him.

Mr. Salman appears to be quite a buff when it comes to participating in the exhibitions and he leaves no stone unturned in introducing Sadequain to the world, but the incongruity is that he exhibits forged copies everywhere and tricks aficionados into buying such objects. When confronted as to why he exhibits phony prints in high profile exhibitions he prefers not to answer. Neither does he put a disclaimer that such exhibited-paintings are inspired illustrations or counterfeits. Taking note of such malpractices, Aicon (New York) and Grosvenor (London) galleries have asked him not to contemplate any further alliance.

A careful assessment of certain specimens of Surah-e-Rahman, published in The Legend of Sadequain, would further unravel the transgressions which have become an integral ingredient of his organization.

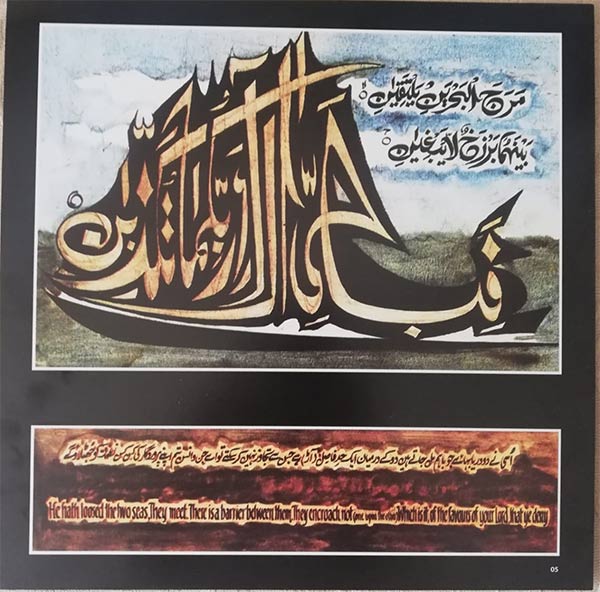

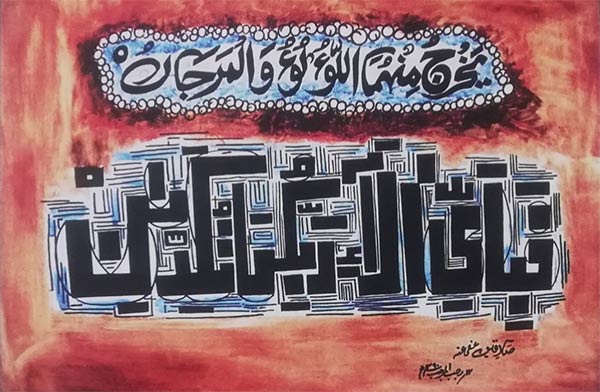

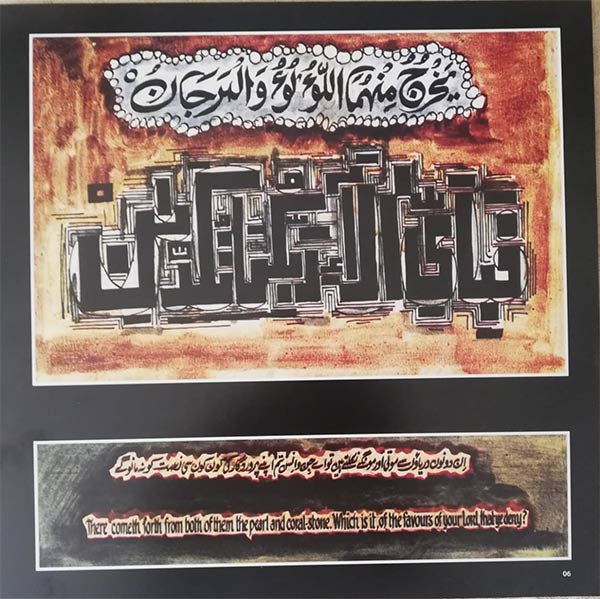

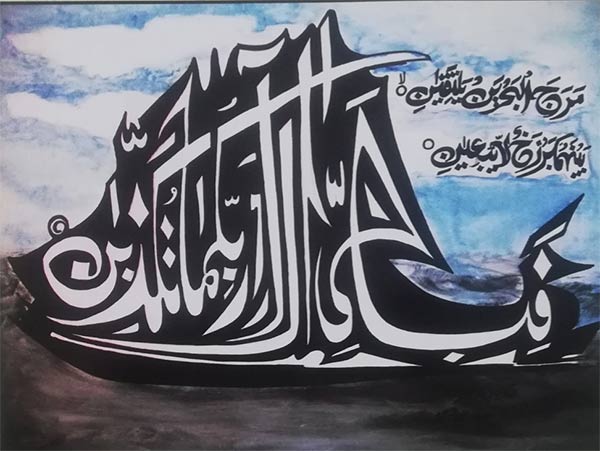

With the assistance of illustrated juxtaposition, any keen observer can discern the divergence between the original and forged copies. Authorities on Sadequain concur that he seldom used autograph on his paintings, but Mr. Salman, to prove his specimens are valid, has embossed all such designs with a conjured signature of the painter. Moreover, the original illustrations drawn in the year 1970 carried the English and Urdu translations of the Quranic verses whereas such a pattern is not evident in the bogus drawings.

A few of the sketches available in the aforesaid text don’t even bear his fitting name which has been vitiated as “Sadqan”. It is not expected from a virtuoso that he would inscribe his name erroneously no matter whatsoever his state of the psyche was.

Furthermore, the prints endorsed by Mr. Salman and those which are authentic have the same dates. It is purely unfounded, if so, on the part of a legend to paint two homogenous series in the same time frame.

Additionally, the original drawings were made of canvas whereas the warped prints have been created on cheap rexine. The originals had decayed gradually, as is natural, and were recently restored at the request of Mr. Sultan Ahmed. It is an exciting observation, though, that the specimens of Mr. Salman still appear afresh as if recently produced.

Sadequain is a global phenomenon and it has been a trend since his life to cash in on his riches. Scoundrels have made use of his bohemian lifestyle and caused him colossal harm. India finds him not only a giant painter and praiseworthy son of its soil, who witnessed a meteoric rise but also an emissary of the Indo-Pak harmony whose calligraphic masterpiece, as a token of love and camaraderie, traveled in 1972 with Mr. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the President of Pakistan, to Simla where it was gifted to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India. The occasion proved a landmark in international politics and both countries inked the famed Simla Agreement on 3rd July 1972. Sadequain’s admirers must preserve his true legacy and debunk those who seek to profit from counterfeiting his works.

The oft-quoted couplet of Allama Iqbal – hazāroñ saal nargis apnī be-nūrī pe rotī hai; baḌī mushkil se hotā hai Chaman meñ dīda-var paidā – aptly describes a prodigy like Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi Amrohvi (June 1930–February 1987) who left his indelible imprints in the sphere of art and literature. His large oeuvre speaks volumes about his incredible journey as a painter and poet, which has elevated him to those rare groups of artists who are as much celebrated today as in their lifetimes. In a posthumous acknowledgment of his work, the government of Pakistan has decided to confer on him Nishan-e-Imtiaz on Pakistan Day (23rd March 2021). Previously, he was awarded Tamgha-e-Imtiaz (March 1960), Pride of Performance (March 1962), and Sitara-e-Imtiaz (March 1980) by the Federal Government, although, it is a subject of enormous significance that he never graced the award functions to receive the laurels. These qualities of Sadequain made him one of his kind and earned him the appellation of Faqir (saint).

Sadly, after his death, people started counterfeiting the works of this Faqir. Hinting at the malpractices prevalent in the art-world, famous scriptwriter Anwar Maqsood once exclaimed that Sadequain made more paintings posthumously than when alive; and hence this article aims to unmask certain mala fide activities, including the deceptive sketches of Surah-e-Rahman, which are being carried out globally in the name of this virtuoso – whose death anniversary on 10th February is close on the heels.

It was during the painstaking research that the present writer stumbled upon one San Diego-based organization, Sadequain Foundation USA, which has been, with impunity, producing sham copies of the artist’s portraits. It was founded and run by one Mr. Salman Ahmad who claims to be a legal heir of Sadequain and dismisses allegations against him as unsubstantiated but the facts point to the contrary. He has published about twelve books on the painter such as The Legend of Sadequain, The Saga of Sadequain, and Lines and Drawings by Sadequain which are replete with spurious information and dodgy prints.

It should not come as a surprise to the art-lovers that he supplied deceptive sketches to the renowned calligrapher, Khursheed Alam Gauhar Qalam when the latter was compiling Khatt-e-Sadequain on the rules and principles of Sadequain’s calligraphy. When Mr. Qalam was confronted in this regard he apologetically accepted his ignorance on the matter and vehemently promised on record that he would speak against the supplier. He found himself a prey of deception by those he trusted; he had pledged to bring out a rationalized account of the book wherein he would rectify all the previous inaccuracies but sadly he passed away before the occasion could arise. What is more surprising is that the eminent art scholar and principal of the National College of Arts in Lahore, Mr. Murtaza Jafri testified to the title by writing a prefatory message to it. When Mr. Jafri was communicated to articulate over the topic he politely declined. The strangest part of the narrative is that since 1974, thirty-two original specimens of the Surah-e-Rahman are accessible for public viewing in the gallery of the National School of Public Policy which is in proximity to the National College of Arts. Those were gifted by the illustrator to the school, which is about to name the gallery after him in the upcoming months. One wonders as to how Mr. Jafri could write a laudatory memorandum without consulting the original portraits. It would not be out of place to register that Mr. Salman himself penned a note for the book, thereby confirming that whatever he had supplied to Mr. Qalam were the authentic illustrations.

During the initial interaction of the present writer with Mr. Salman, he appeared very suave and courteous and was ready to furnish all the niceties about Sadequain. Gradually the undercurrents of his conversations became distinct and he got more interested in selling the voluminous tomes he had penned on the illustrator, but somewhere down the line, his aggravation got obvious when he was regularly enquired about certain irrational aspects of the publications about which the present writer had developed doubts.

Beginning with Mr. Salman’s book, The Legend of Sadequain, wherein he writes that the painter had composed four complete versions of Surah-e-Rahman comprising two sets of thirty-one panels and another two of forty panes; but in a Facebook post that he updates later, which contradicts his recorded statement in the text, he asserts that Sadequain had composed only three sets of the aforesaid holy Quranic verses in 1969, 1974 and 1980. Though, in reality, it should be broached here that the visual artist had composed three versions in the years 1970, 1974, and 1981. One might ask as to how he could carve a long array of opuses on Sadequain when he remains ignorant about the years when the authority was creating his awe-inspiring drawings. Such divergent views are extremely recurrent with Mr. Salman and, thus, he could be anyone but a legitimate benefactor of art.

He adds to his post that he had purchased thirty-one phony portraits from one Mr. Ishrat Hussain, whom he calls a scoundrel, of Karachi and he uses such prints to exhibit globally and introduce the Khatt-e-Sadequani i.e. Sadequains’ font. If one goes by his statements he has used such designs in at least twelve exhibitions and three publications on the painter. The question arises as to what drives him to exploit such counterfeit copies which he has already termed deceptive.

Furthermore, he has not published the original impressions of Surah-e-Rahman in his aforementioned tome, neither has he incorporated bona fide specimens in his other texts on Sadequain. Instead what one finds in such compilations are the bogus drawings that his foundation has been churning out since 2007.

If he were a genuine sponsor of the art he would publish the works which are on display at the National School of Public Policy, but he avoided doing since he wanted to showcase the forged paintings for commercial reasons and to sell them.

Despite all the claims by Mr. Salman about his credentials, it is startling to discover that no reputed newspaper of Pakistan has so far reviewed any of his lengthy assortment of works, neither have there been any announcements of the book-launches. He received further backlash when distinguished organizations and galleries such as Anujman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu, Arts Council of Pakistan-Karachi, Frere Hall, Mohatta Palace, Lahore Museum, Alhamra Arts Council, etc. severed ties with him on account of his varied dubious activities. Pakistan National Council of Arts and the State Bank Museum of Pakistan in Karachi, which are studded with lavish murals by Sadequain, have also cut off their associations with him.

Mr. Salman appears to be quite a buff when it comes to participating in the exhibitions and he leaves no stone unturned in introducing Sadequain to the world, but the incongruity is that he exhibits forged copies everywhere and tricks aficionados into buying such objects. When confronted as to why he exhibits phony prints in high profile exhibitions he prefers not to answer. Neither does he put a disclaimer that such exhibited-paintings are inspired illustrations or counterfeits. Taking note of such malpractices, Aicon (New York) and Grosvenor (London) galleries have asked him not to contemplate any further alliance.

A careful assessment of certain specimens of Surah-e-Rahman, published in The Legend of Sadequain, would further unravel the transgressions which have become an integral ingredient of his organization.

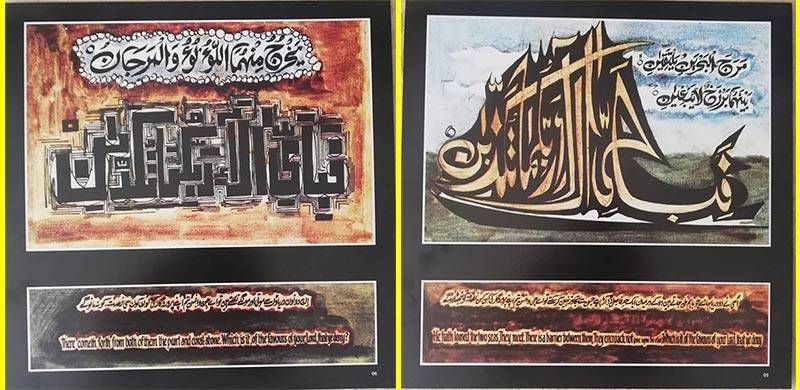

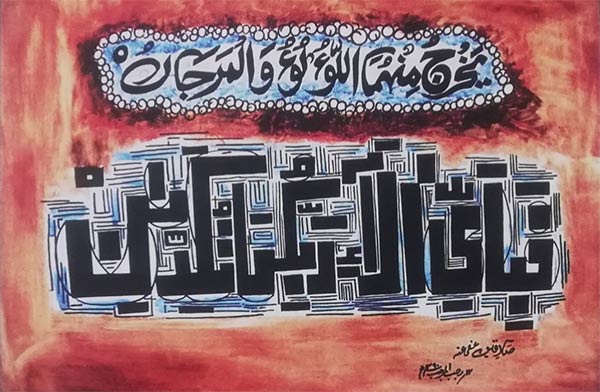

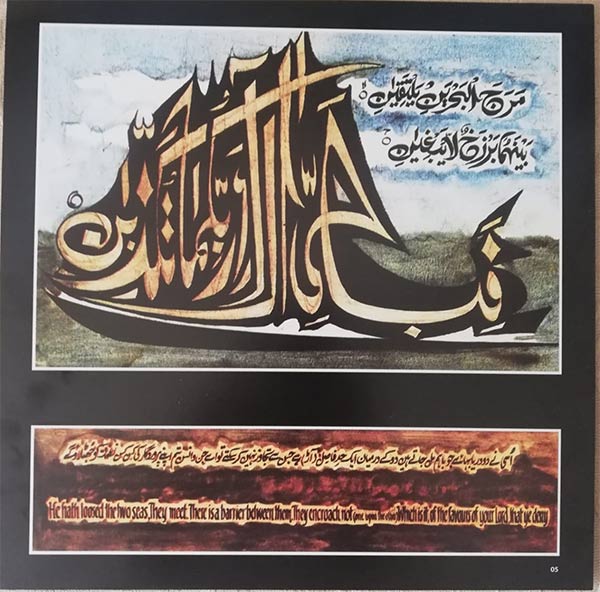

Figure 1 (a): Forged Surah-e-Rahman (published in The Legend of Sadequain)

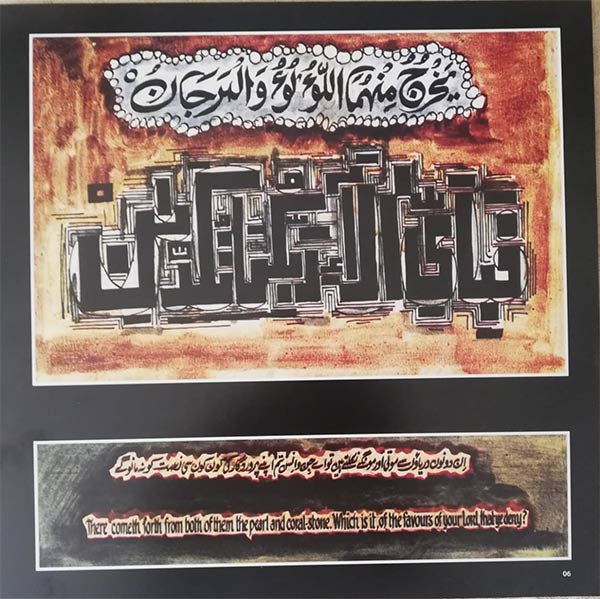

Figure 1 (b): Original Surah-e-Rahman as painted by Sadequain in 1970 and currently displayed at National School of Public Policy

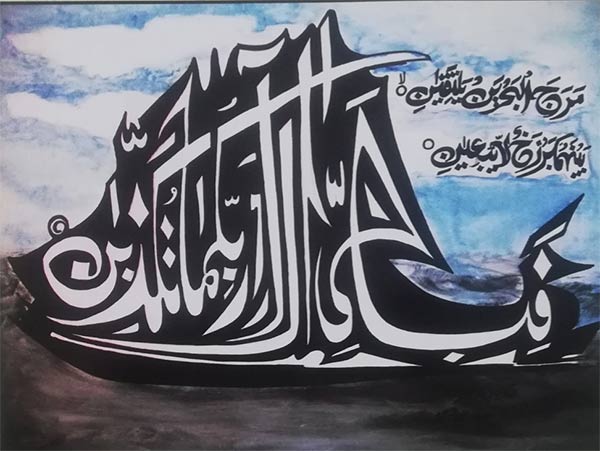

Figure 2 (a): Forged Surah-e-Rahman (published in The Legend of Sadequain)

Figure 2 (b): Original Surah-e-Rahman as painted by Sadequain in 1970 and currently displayed National School of Public Policy

With the assistance of illustrated juxtaposition, any keen observer can discern the divergence between the original and forged copies. Authorities on Sadequain concur that he seldom used autograph on his paintings, but Mr. Salman, to prove his specimens are valid, has embossed all such designs with a conjured signature of the painter. Moreover, the original illustrations drawn in the year 1970 carried the English and Urdu translations of the Quranic verses whereas such a pattern is not evident in the bogus drawings.

A few of the sketches available in the aforesaid text don’t even bear his fitting name which has been vitiated as “Sadqan”. It is not expected from a virtuoso that he would inscribe his name erroneously no matter whatsoever his state of the psyche was.

Furthermore, the prints endorsed by Mr. Salman and those which are authentic have the same dates. It is purely unfounded, if so, on the part of a legend to paint two homogenous series in the same time frame.

Additionally, the original drawings were made of canvas whereas the warped prints have been created on cheap rexine. The originals had decayed gradually, as is natural, and were recently restored at the request of Mr. Sultan Ahmed. It is an exciting observation, though, that the specimens of Mr. Salman still appear afresh as if recently produced.

Sadequain is a global phenomenon and it has been a trend since his life to cash in on his riches. Scoundrels have made use of his bohemian lifestyle and caused him colossal harm. India finds him not only a giant painter and praiseworthy son of its soil, who witnessed a meteoric rise but also an emissary of the Indo-Pak harmony whose calligraphic masterpiece, as a token of love and camaraderie, traveled in 1972 with Mr. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the President of Pakistan, to Simla where it was gifted to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India. The occasion proved a landmark in international politics and both countries inked the famed Simla Agreement on 3rd July 1972. Sadequain’s admirers must preserve his true legacy and debunk those who seek to profit from counterfeiting his works.