In February, 2008, a team of American Senators visited Pakistan—the team included John Kerry, who later served as President Obama’s Secretary of State and Joe Biden, who has just been elected as the President of the United states. The aim of the visit was to assess the economic, financial and military needs of a key ally in “War against Terror”. The team of senators held meetings with key military and political leaders in Islamabad before embarking on a tour of neighboring Afghanistan and India. Pakistan was holding parliamentary elections in the same month the team of senators visited Islamabad. The country was about to transition into a full parliamentary democratic setup after nine years of dark military rule. From every perspective, Washington’s South Asian ally appeared highly unstable—this was a period of rampant terrorism as Pakistan security forces were still reluctantly pursuing militants in the tribal areas and as a reaction the militants were carrying out terror attacks in the urban areas. The high point of terror campaign was witnessed in Rawalpindi—the military headquarters—when former Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto and a serving Lt General of Pakistan Army were killed in a suicide attacks in the garrison city, in two separate incidents.

Pakistan was in dire need of military and financial assistance to cope with the rising threat of militancy and the associated dangers of financial meltdown. In this situation American media and experts started to report that the team of senators that included Senator Joe Biden had concluded that “the United States has to make a large-scale aid commitment to Pakistan “. American media described that visit of American Senators to Islamabad as the origin of the legislation ultimately known as Kerry-Lugar-Berman” that committed $1.5 billion annual in financial aid to Pakistan. The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) came to power in Islamabad as a result of the February 2008 parliamentary election much before the aid bill was presented in the US senate. Within a year Joe Biden was elected Vice President of the United States as an election-mate of President Obama, so the Kerry-Biden Bill was converted into Kerry-Lugar Bill. But Vice President Joe Biden continued to be the driving force behind the bill even after it was presented before the US senate for passage.

In 2008, Pakistan was making a transition towards parliamentary democracy and the then Bush Administration in Washington and its key officials remained actively engaged in making this transition a possibility. Bush Administration’s key officials were acting as a go-between the military dictator, General Musharraf and PPP leader, Benazir Bhutto to provide a political base to this period of transition, which was about to take place in Pakistan after the scheduled parliamentary elections. The then senator Joe Biden was not part of the Bush administration at that time, but he was prominent in making parallel efforts in US legislation to revive democracy in Pakistan. This he did by making financial and military assistance conditional with the principle of civilian supremacy.

Original Bill—a product of President Biden’s thinking as a senator—included a provision for the US Secretary of State’s to certificate about civilian supremacy in Pakistan before the disbursement of financial aid to Pakistan. Actually the Bill involved the issuance of three pre-disbursement certifications by the US Secretary of State. The first certification clause was the one warranting Pakistan’s continued cooperation “on the dismantling of nuclear weapon-related supplier networks and providing relevant information from or direct access to Pakistani nationals associated with such networks.”

The other certification pertained to Pakistan’s commitment to “combating terrorist groups, ceasing support, including by any elements within Pakistan military or its intelligence agency to extremists and terrorist groups, preventing Al Qaeda, the Taliban and associated terrorist groups from operating in its territory or launching cross-border attacks into neighboring countries and dismantling of terrorist operation bases on its soil including Quetta and Muridke. Perhaps the last certification requirement was the one to assure the Congress that Pakistan’s “security forces are not materially and substantially subverting the political or judicial processes of the country.”

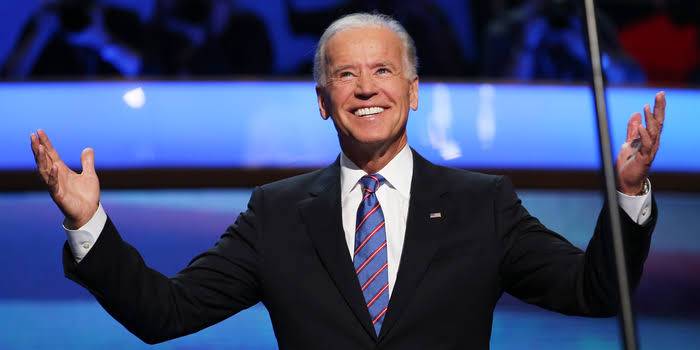

President Joe Biden is considered a “Liberal Internationalist”—a school of thought in Washington that sees managing and policing the international system of states and its crises as a moral responsibility of the United States of America—within the ideological spectrum of American political thought. His diatribes against dictators, racist rulers and human rights violations have been doing the rounds on social media since his victory became obvious. And in Pakistan’s media and political circles, President Joe Biden’s policies towards democracy and its possible impact on Pak-US relations has already been a subject of discussion.

Unlike 2008, Pakistan, at present, is a full-fledged parliamentary democracy. There, however, are voices within the society which are questioning the quality of democracy in the country. Similarly, there are strong voices in Pakistan accusing the government of curbing media freedoms in the country. How will Washington under President Joe Biden see the situation in Pakistan? Is there a possibility that Washington may pressure Islamabad on the question of granting more freedom to the media? Can the new situation in Washington ensure that the prosecution of opposition political forces in Pakistani society comes to an end as opposition is accusing the government of witch hunt? Or more broadly speaking how the new “Liberal Internationalism” political philosophy of Washington would impact countries like Pakistan? These similar questions will require answers as President Biden embarks on formulating foreign policy of his administration.