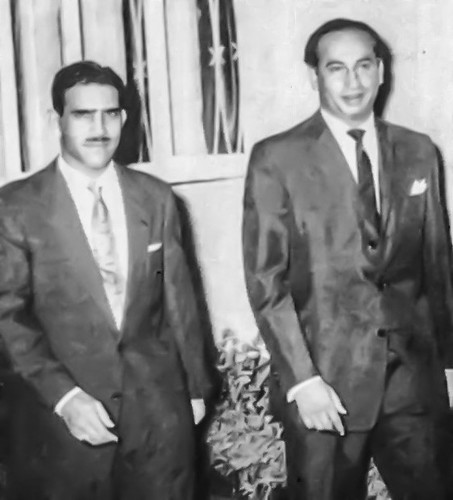

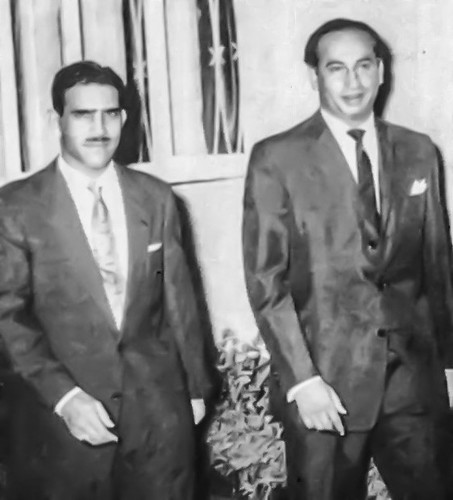

Sherbaz Khan Mazari passed away this month at the age of 90. He was one of Pakistan’s pre-eminent politicians and the founder of the National Democratic Party. He was also the brother-in-law of Nawab Akbar Bugti who was killed on General Musharraf’s orders.

Mazari has left behind a rich legacy. He contested the 1970 elections in December as an independent and won a seat in the National Assembly. These elections continue to be regarded as the fairest in the nation’s history. In March 1971 the military government headed by General Yahya Khan annulled the results of the elections and unleashed the fury of the army against the Awami League which had won majority of the seats in the National Assembly. Yahya was egged on by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto whose Peoples Party had won the second highest seats in the elections.

Mazari was one of the few elected politicians in West Pakistan who opposed military action in East Pakistan. Once the East was surrendered to India, the army removed Yahya from the office and installed Bhutto as the President and Chief Martial Law Administrator. Bhutto began rallying the population to create a New Pakistan. He took on the task of drafting a new constitution.

Mazari worked with Bhutto and others in the National Assembly to draft the constitution which was passed in 1973. It represented a new beginning for a country that was traumatized by the debacle of 1971.

Mazari worked with Bhutto and others in the National Assembly to draft the constitution which was passed in 1973. It represented a new beginning for a country that was traumatized by the debacle of 1971.

From 1975 to 1977, Mazari was a vocal member of the opposition in the National Assembly and played an active role in the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy. The army returned to power in 1977 and began to hand pick politicians that would serve as its puppets in the decade that followed.

In 1988, General Zia died in a still mysterious plane crash. The army returned power to the civilians, beginning with Benazir Bhutto of the Peoples Party and later to Nawaz Sharif of the Muslim League. Unfortunately, the country experienced lacklustre economic growth while corruption intensified.

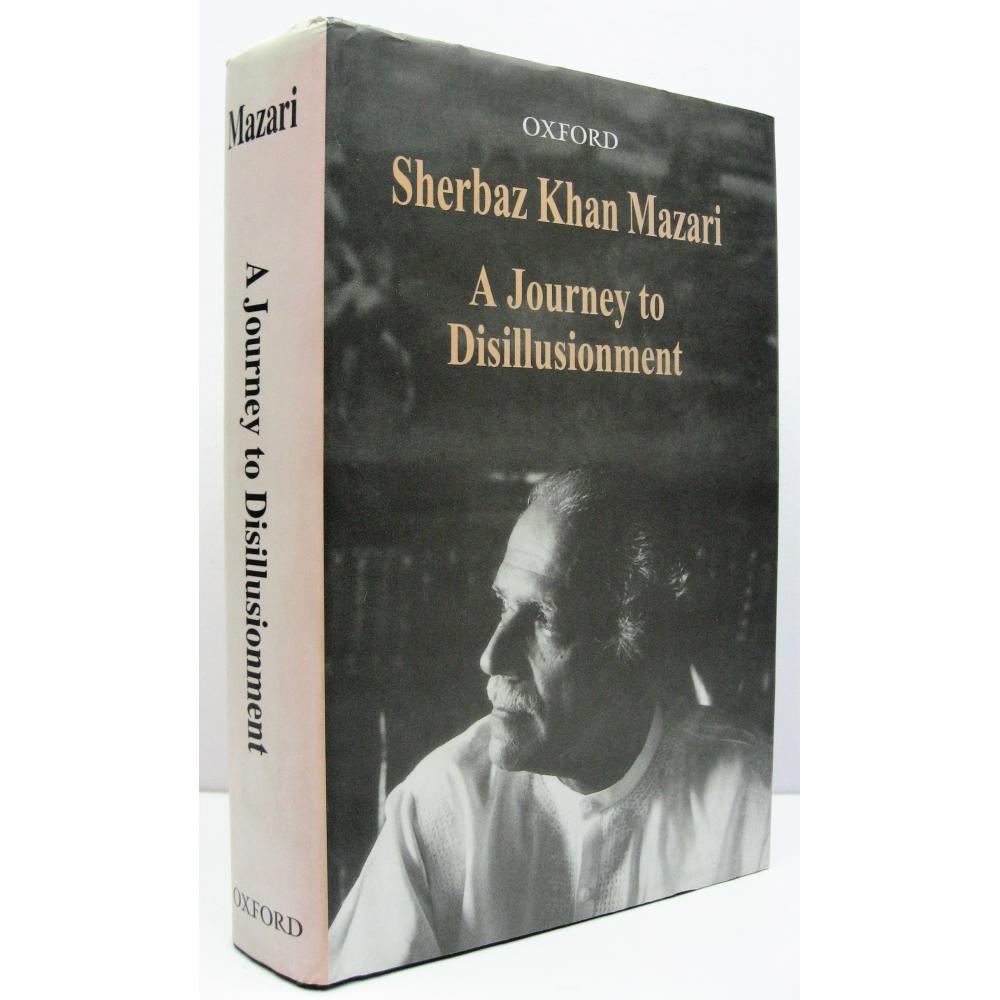

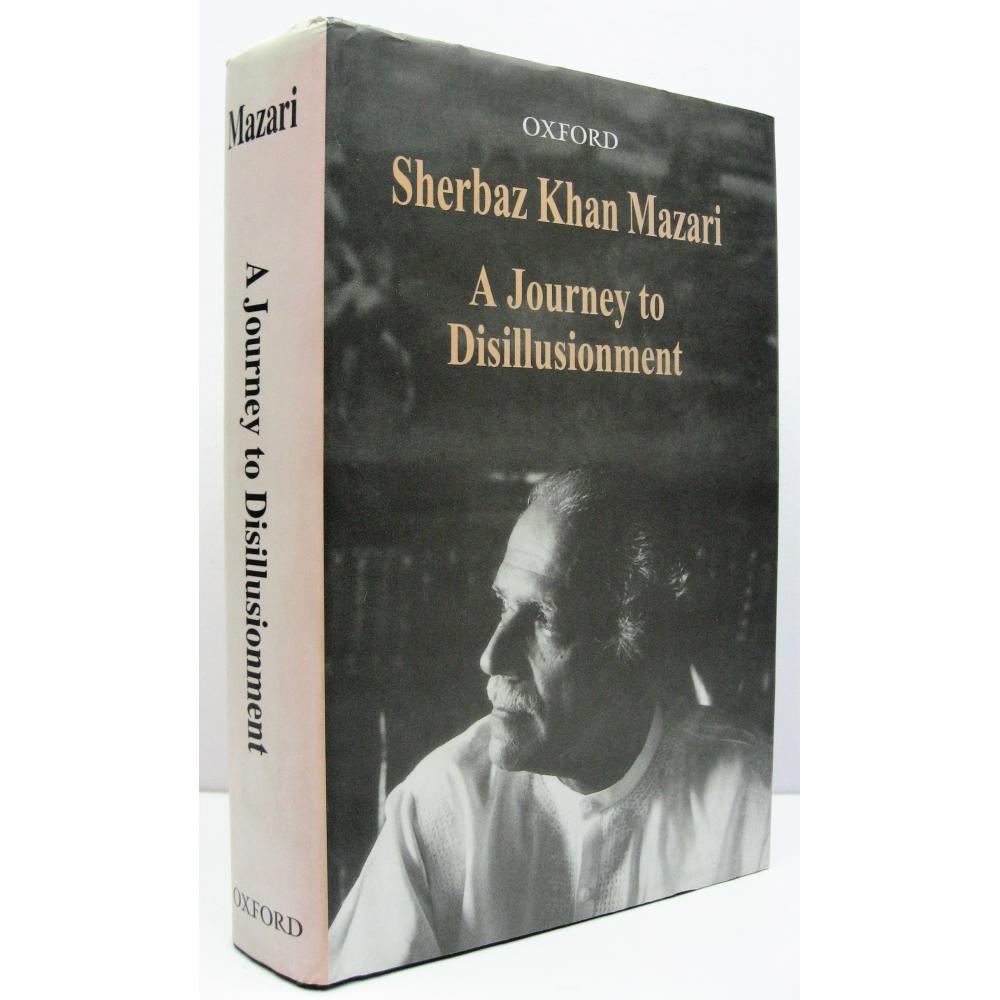

Dismayed, in 1999, Mazari penned a poignant memoir, “A Journey to Disillusionment.” The book came out at a time when a spate of books with morose titles were being published, such as Pakistan: The Barren Years, Pakistan: Leadership Challenges, and Pakistan: A Dream Gone Sour.

Mazari’s memoir carried more weight because he had been a member of the National Assembly. Furthermore, he had schooled in pre-partition India at the Royal Indian Military College at Dehradun with several people who rose to senior positions in the army including Generals; Tikka Khan and Yahya Khan.

Mazari observed that since its creation 52 years ago, Pakistan’s development had been marred by coups carried out by generals stating that the country had “hit rock bottom.” The generals claimed that the country had been ruined by politicians who were worse than “sharks and leeches.” In turn, the politicians would blame the generals for deposing them from office and committing treason.

Mazari concluded that both were to blame. He also castigated the bureaucracy for allowing itself to become a handmaiden of whoever happened to be ruling the country. He details the brazen manner in which these three groups plundered the nation’s wealth.

The book also chronicles the long list of failures in the wars against India. He traces them to poor leadership brought on by the promotion of officers based on loyalty rather than merit.

It is the analysis of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s character that sets this book apart from many others. Over a period of 23 years, Bhutto progressed from being “a despondent political aspirant … to a civilian martial law administrator and president.” He had an unbridled lust for power, and a dark admiration for Adolph Hitler. His library at 70 Clifton in Karachi stored what was possibly the largest collection of books about the Fuhrer in Pakistan. It also had a large collection of books about Napoleon. Mazari states that “lying, double-dealing and deceit” were Bhutto’s “normal” means of attaining and keeping power.

In the Epilogue, he reminisces about three tragic events in Pakistani history. The first occurred in 1954 when the Supreme Court connived with the Governor General and “over-rode the sovereign authority of the Constituent Assembly.” The second was Bhutto’s rule in 1971-77. His totalitarian politics destroyed all national institutions. Opponents, even former mentors, were brutalized in unspeakable terms by his secret police, the Federal Security Force. Mazari lays the blame for Zia’s 11 years of draconian rule squarely on Bhutto’s shoulders.

The third and final event was the refusal by Bhutto’s daughter in 1988 to abide by the democratic principles that had brought her into power. She bequeathed a “legacy of political hatred that terminally weakened the give-and-take nature of democratic politics” and brought into power Zia's protégé, Nawaz Sharif. It was Sharif’s wayward rule that precipitated General Musharraf’s coup in 1999.

Mazari lamented that “the journey, that I had started so long ago, full of hopes and high aspirations, had ended in disillusionment.” Unfortunately, while providing an eloquent testimony to how paradise was lost by the venal leaders of Pakistan, Mazari offered no thoughts on how paradise would be regained. Perhaps he had lost hope.

In 2011, Anatol Lieven published his book, “Pakistan: A Hard Country.” He echoed Mazari’s conclusions. He said that all of Pakistan’s leaders, democratic and dictators alike, had failed to change the ground realities. “Every single one of them found their regimes ingested by the elites they had hoped to displace, and engaged in the same patronage politics as the regimes they had overthrown.”

As the year 2020 draws to a close a new book has appeared with an ominous title, “The Nine Lives of Pakistan” and an even more ominous subtitle, “Dispatches from a Precarious State.” Little has changed since Mazari penned his memoirs.

Every new ruler comes to power promising change but fails to deliver change. In late December 1971, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to power and spoke of creating a New Pakistan. Mazari aptly describes what he did.

In 2018, Imran Khan came to power promising tabdeeli (change) and spoke of creating a Naya (new) Pakistan. The fundamentals of the country have not changed on his watch. Kashmir remains a disputed territory. The economy continues to suffer. His cabinet is drawn from former cabinets. The army calls the shots.

In light of the prevailing predicament, the French saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” comes to mind.

Mazari has left behind a rich legacy. He contested the 1970 elections in December as an independent and won a seat in the National Assembly. These elections continue to be regarded as the fairest in the nation’s history. In March 1971 the military government headed by General Yahya Khan annulled the results of the elections and unleashed the fury of the army against the Awami League which had won majority of the seats in the National Assembly. Yahya was egged on by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto whose Peoples Party had won the second highest seats in the elections.

Mazari was one of the few elected politicians in West Pakistan who opposed military action in East Pakistan. Once the East was surrendered to India, the army removed Yahya from the office and installed Bhutto as the President and Chief Martial Law Administrator. Bhutto began rallying the population to create a New Pakistan. He took on the task of drafting a new constitution.

Mazari worked with Bhutto and others in the National Assembly to draft the constitution which was passed in 1973. It represented a new beginning for a country that was traumatized by the debacle of 1971.

Mazari worked with Bhutto and others in the National Assembly to draft the constitution which was passed in 1973. It represented a new beginning for a country that was traumatized by the debacle of 1971.From 1975 to 1977, Mazari was a vocal member of the opposition in the National Assembly and played an active role in the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy. The army returned to power in 1977 and began to hand pick politicians that would serve as its puppets in the decade that followed.

In 1988, General Zia died in a still mysterious plane crash. The army returned power to the civilians, beginning with Benazir Bhutto of the Peoples Party and later to Nawaz Sharif of the Muslim League. Unfortunately, the country experienced lacklustre economic growth while corruption intensified.

Dismayed, in 1999, Mazari penned a poignant memoir, “A Journey to Disillusionment.” The book came out at a time when a spate of books with morose titles were being published, such as Pakistan: The Barren Years, Pakistan: Leadership Challenges, and Pakistan: A Dream Gone Sour.

Mazari’s memoir carried more weight because he had been a member of the National Assembly. Furthermore, he had schooled in pre-partition India at the Royal Indian Military College at Dehradun with several people who rose to senior positions in the army including Generals; Tikka Khan and Yahya Khan.

Mazari observed that since its creation 52 years ago, Pakistan’s development had been marred by coups carried out by generals stating that the country had “hit rock bottom.” The generals claimed that the country had been ruined by politicians who were worse than “sharks and leeches.” In turn, the politicians would blame the generals for deposing them from office and committing treason.

Mazari concluded that both were to blame. He also castigated the bureaucracy for allowing itself to become a handmaiden of whoever happened to be ruling the country. He details the brazen manner in which these three groups plundered the nation’s wealth.

The book also chronicles the long list of failures in the wars against India. He traces them to poor leadership brought on by the promotion of officers based on loyalty rather than merit.

It is the analysis of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s character that sets this book apart from many others. Over a period of 23 years, Bhutto progressed from being “a despondent political aspirant … to a civilian martial law administrator and president.” He had an unbridled lust for power, and a dark admiration for Adolph Hitler. His library at 70 Clifton in Karachi stored what was possibly the largest collection of books about the Fuhrer in Pakistan. It also had a large collection of books about Napoleon. Mazari states that “lying, double-dealing and deceit” were Bhutto’s “normal” means of attaining and keeping power.

In the Epilogue, he reminisces about three tragic events in Pakistani history. The first occurred in 1954 when the Supreme Court connived with the Governor General and “over-rode the sovereign authority of the Constituent Assembly.” The second was Bhutto’s rule in 1971-77. His totalitarian politics destroyed all national institutions. Opponents, even former mentors, were brutalized in unspeakable terms by his secret police, the Federal Security Force. Mazari lays the blame for Zia’s 11 years of draconian rule squarely on Bhutto’s shoulders.

The third and final event was the refusal by Bhutto’s daughter in 1988 to abide by the democratic principles that had brought her into power. She bequeathed a “legacy of political hatred that terminally weakened the give-and-take nature of democratic politics” and brought into power Zia's protégé, Nawaz Sharif. It was Sharif’s wayward rule that precipitated General Musharraf’s coup in 1999.

Mazari lamented that “the journey, that I had started so long ago, full of hopes and high aspirations, had ended in disillusionment.” Unfortunately, while providing an eloquent testimony to how paradise was lost by the venal leaders of Pakistan, Mazari offered no thoughts on how paradise would be regained. Perhaps he had lost hope.

In 2011, Anatol Lieven published his book, “Pakistan: A Hard Country.” He echoed Mazari’s conclusions. He said that all of Pakistan’s leaders, democratic and dictators alike, had failed to change the ground realities. “Every single one of them found their regimes ingested by the elites they had hoped to displace, and engaged in the same patronage politics as the regimes they had overthrown.”

As the year 2020 draws to a close a new book has appeared with an ominous title, “The Nine Lives of Pakistan” and an even more ominous subtitle, “Dispatches from a Precarious State.” Little has changed since Mazari penned his memoirs.

Every new ruler comes to power promising change but fails to deliver change. In late December 1971, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to power and spoke of creating a New Pakistan. Mazari aptly describes what he did.

In 2018, Imran Khan came to power promising tabdeeli (change) and spoke of creating a Naya (new) Pakistan. The fundamentals of the country have not changed on his watch. Kashmir remains a disputed territory. The economy continues to suffer. His cabinet is drawn from former cabinets. The army calls the shots.

In light of the prevailing predicament, the French saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” comes to mind.