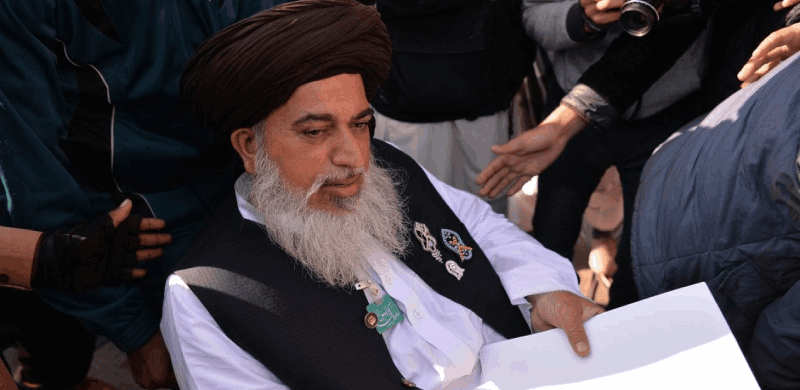

The immediate hot takes that were ricocheting across social media right after the death of Khadim Hussain Rizvi, leader of the Tehreek e Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), revealed a persisting unrest amongst progressive thinkers in Pakistan.

The left-leaners felt that Rizvi deserved to be mourned for his rabble-rousing street cred amongst the neglected and unwashed masses, even if his politics exhorted not class warfare but hate, misogyny and death for perceived apostates, blasphemers and secular collaborators. The liberals, temporarily suspended their political correctness to respond with relief, mockery, and memes. They even spared the talented M. Hanif of scorn for setting up ‘binaries’ in an article which contrasted the politics of the foul-mouthed Auqaf employee, Khadim Rizvi, from that of liberal human rights lawyer, Asma Jahangir.

These diverse political reactions also raise the larger question about when critique is acceptable in snide, sardonic, satirical form and when it is condemnable as injurious, racist and orientalist. It’s not just form – the inconsistencies are a legacy of unresolved and personalised debates in the post 9/11 era. Unknown terms in prior activist politics, the progressives became sub-categorised as liberal-secularists and the ‘real’ anti-imperialists. The division hardened many disagreements over the victim/insurgent identity of the TTP, drone versus conventional warfare, the Lal Masjid siege and the role of madrassas. But it has been the criticism of every day piety movements and ‘moderate Islam’ that encouraged a younger generation of post 9/11 Pakistani ‘radicals’ – based anywhere in the world – to be fiercely critical of other activists for their ‘liberal-secular’ and congruently, imperialist politics.

Although, piety or tableeghi politics was historically a masculinist project – the emergence of women’s mosque movements feminised this (especially in Egypt and the Al-Huda in Pakistan) and made these women the subject of countless theses and publications in the post 9/11 period. This came at the cost of research interest in any other, class or secular, identities of Muslim women.

Unlike feminist understanding of violence against women – which interconnects online harassment all the way to rape on the same spectrum – the politics of piety have been exceptionalised as distinct from religious politics. Pietist identities have been filtered as viable alternatives to liberal ones and even as a working-class counter-concept to the ‘elite’ secular impositions of the west, the state, and feminism.

One obvious challenge to this piety-exceptionalism theory in Pakistan was of course, the Lal Masjid and Jamia Hafsa (JH) uprisings of 2007. Not only did this event expose the misleading studies and publications that ignored the nexus of extremist groups with moderate ones and the role of establishment sponsorship, but many commentators refused to deal with the immediate schisms in the piety-as-self-empowerment theories by denying the exercise of this agency by the women of JH.

Instead, the liberals condemned this inconvenient radical politics and considered the women to be dupes of false consciousness or male direction and, the anti-imperialists blamed the establishment, war on terror, imperialism and poverty for what is a very localised conscious politics that resonates with many.

Such deflections were fated to rebound, as they did when the women of Minhaj ul Quran and JH protested against the series of Aurat Marches (AM) held over the past 3 years. This clear flouting of the piety-as-a-docile-empowerment theory that is otherwise academically defended, was again met with convenient silence. And again, this March in Rawalpindi, when women of the JH vandalised the sisterhood mural prepared for Aurat March and the march itself was attacked by the pious right, there followed no honest reckoning by the post-secularists or anti-imperialists about the politics of these pietist movements, or how they exercised their agency, or how to strategise when this directly targets feminist politics.

All the angry lectures to other feminists about “engagement” and “understanding” were reserved only for social media outrage and applause for online bravado. The contradictions that spill over inconveniently from theses and theory seem not to warrant response when in play. This is unfortunate because feminist praxis depends on connecting theory with activism.

Many progressives in Pakistan pretend there is no oppositional politics but inherent compatibility between religious and secular politics because they simply avoid the contradictions repeatedly and cover this with well-written postcolonial affective rhetoric about overarching liberal imperialism.

These lingering issues of selectivity and contradictory standards became obvious on Rizvi’s death. Why was there a special loathing for the KHR brand of piety that justified liberal antipathy even amongst those who object to Islamophobia and defend pious agency? All the other pietist movements including Al-Huda, are outspokenly anti-India, nationalist, varyingly sectarian and viciously anti-Ahmedi and pro-blasphemy and, have indisputable connections with the state establishment, regardless of ‘depth’. The deflection of blaming the establishment pretends that KHR is the first and only proxy or pawn, or that despite that, these movements can have no organic following, or electoral appeal, or independent political ambitions, agency, agenda or charisma in their leaders. (As a proviso though, to those who do keep harping on about this point, do we have any non-charismatic political party leader these days?... Bajwa doesn’t count. Also, should charisma be a qualified description when it is committed to fascistic ends?).

Rizvi’s movement converted into electoral success in 2018 in a record breaking manner that nearly equalised the combined JUI and MMA votes but also, stole votes away from the PML-N in Punjab. A Gallup Exit Poll conducted in 127 constituencies claimed that “46 percent of TLP voters stated that they had voted for PML-N in 2013," confirming that a significant number of the PML-N voters had shifted loyalties to the TLP. Respondents affirmed how inspired they were by Rizvi’s campaign message which warned voters that they would be answerable on the Day of Judgement if they didn’t vote for his party. The PML-N was successfully painted as a profane (if not secular) party and even Hafiz Saeed’s son justified ending allegiance because according to him, Nawaz Sharif had changed his stance on Kashmir and India. Voters are exercising independent agency too, when they vote for religious leaders.

The poststructuralist and post-secular scholars have taken ethnographic pains to show how performativity is not just some stunt but almost a romantic ritualistic, self-disciplinary act to achieve virtue (a pietist subject is even described as a ‘virtuouso’ aspirant). Is it then simply that it was Rizvi’s profanities, and lack of aesthetics and middle-class politesse, that disqualified him as the virtuoso teacher and made him the inconvenient maulvi, instead?

The left-leaners who do real politics understand this but make a fetish of Rizvi’s appeal to the working classes with no evidence of his commitment to a single class-based issue or delivery of material rights. They would not credit the PPP or ANP for this even though, they do receive class-conscious votes. Is it leadership and following, not agenda that determines class identity? In which case, our left political leadership needs to seriously rethink its own composition.

How long before we reconcile that the working classes are not just non-liberal victims but can have liberal and/or secular aspirations too? And that many can be politically motivated bigots and misogynists. Instead of some misplaced infantilising calls to respect and indulge this for its decolonising potential, or pray for divine intervention, it is time for progressives to challenge such politics and be consistent in doing so. Otherwise, we can just wait for what will be the next charismatic virtuoso teacher for some, and the unclean inconvenient mullah for others but the base contradictions will continue to haunt us.

The left-leaners felt that Rizvi deserved to be mourned for his rabble-rousing street cred amongst the neglected and unwashed masses, even if his politics exhorted not class warfare but hate, misogyny and death for perceived apostates, blasphemers and secular collaborators. The liberals, temporarily suspended their political correctness to respond with relief, mockery, and memes. They even spared the talented M. Hanif of scorn for setting up ‘binaries’ in an article which contrasted the politics of the foul-mouthed Auqaf employee, Khadim Rizvi, from that of liberal human rights lawyer, Asma Jahangir.

These diverse political reactions also raise the larger question about when critique is acceptable in snide, sardonic, satirical form and when it is condemnable as injurious, racist and orientalist. It’s not just form – the inconsistencies are a legacy of unresolved and personalised debates in the post 9/11 era. Unknown terms in prior activist politics, the progressives became sub-categorised as liberal-secularists and the ‘real’ anti-imperialists. The division hardened many disagreements over the victim/insurgent identity of the TTP, drone versus conventional warfare, the Lal Masjid siege and the role of madrassas. But it has been the criticism of every day piety movements and ‘moderate Islam’ that encouraged a younger generation of post 9/11 Pakistani ‘radicals’ – based anywhere in the world – to be fiercely critical of other activists for their ‘liberal-secular’ and congruently, imperialist politics.

Although, piety or tableeghi politics was historically a masculinist project – the emergence of women’s mosque movements feminised this (especially in Egypt and the Al-Huda in Pakistan) and made these women the subject of countless theses and publications in the post 9/11 period. This came at the cost of research interest in any other, class or secular, identities of Muslim women.

Unlike feminist understanding of violence against women – which interconnects online harassment all the way to rape on the same spectrum – the politics of piety have been exceptionalised as distinct from religious politics. Pietist identities have been filtered as viable alternatives to liberal ones and even as a working-class counter-concept to the ‘elite’ secular impositions of the west, the state, and feminism.

One obvious challenge to this piety-exceptionalism theory in Pakistan was of course, the Lal Masjid and Jamia Hafsa (JH) uprisings of 2007. Not only did this event expose the misleading studies and publications that ignored the nexus of extremist groups with moderate ones and the role of establishment sponsorship, but many commentators refused to deal with the immediate schisms in the piety-as-self-empowerment theories by denying the exercise of this agency by the women of JH.

Instead, the liberals condemned this inconvenient radical politics and considered the women to be dupes of false consciousness or male direction and, the anti-imperialists blamed the establishment, war on terror, imperialism and poverty for what is a very localised conscious politics that resonates with many.

Such deflections were fated to rebound, as they did when the women of Minhaj ul Quran and JH protested against the series of Aurat Marches (AM) held over the past 3 years. This clear flouting of the piety-as-a-docile-empowerment theory that is otherwise academically defended, was again met with convenient silence. And again, this March in Rawalpindi, when women of the JH vandalised the sisterhood mural prepared for Aurat March and the march itself was attacked by the pious right, there followed no honest reckoning by the post-secularists or anti-imperialists about the politics of these pietist movements, or how they exercised their agency, or how to strategise when this directly targets feminist politics.

All the angry lectures to other feminists about “engagement” and “understanding” were reserved only for social media outrage and applause for online bravado. The contradictions that spill over inconveniently from theses and theory seem not to warrant response when in play. This is unfortunate because feminist praxis depends on connecting theory with activism.

Many progressives in Pakistan pretend there is no oppositional politics but inherent compatibility between religious and secular politics because they simply avoid the contradictions repeatedly and cover this with well-written postcolonial affective rhetoric about overarching liberal imperialism.

These lingering issues of selectivity and contradictory standards became obvious on Rizvi’s death. Why was there a special loathing for the KHR brand of piety that justified liberal antipathy even amongst those who object to Islamophobia and defend pious agency? All the other pietist movements including Al-Huda, are outspokenly anti-India, nationalist, varyingly sectarian and viciously anti-Ahmedi and pro-blasphemy and, have indisputable connections with the state establishment, regardless of ‘depth’. The deflection of blaming the establishment pretends that KHR is the first and only proxy or pawn, or that despite that, these movements can have no organic following, or electoral appeal, or independent political ambitions, agency, agenda or charisma in their leaders. (As a proviso though, to those who do keep harping on about this point, do we have any non-charismatic political party leader these days?... Bajwa doesn’t count. Also, should charisma be a qualified description when it is committed to fascistic ends?).

Rizvi’s movement converted into electoral success in 2018 in a record breaking manner that nearly equalised the combined JUI and MMA votes but also, stole votes away from the PML-N in Punjab. A Gallup Exit Poll conducted in 127 constituencies claimed that “46 percent of TLP voters stated that they had voted for PML-N in 2013," confirming that a significant number of the PML-N voters had shifted loyalties to the TLP. Respondents affirmed how inspired they were by Rizvi’s campaign message which warned voters that they would be answerable on the Day of Judgement if they didn’t vote for his party. The PML-N was successfully painted as a profane (if not secular) party and even Hafiz Saeed’s son justified ending allegiance because according to him, Nawaz Sharif had changed his stance on Kashmir and India. Voters are exercising independent agency too, when they vote for religious leaders.

The poststructuralist and post-secular scholars have taken ethnographic pains to show how performativity is not just some stunt but almost a romantic ritualistic, self-disciplinary act to achieve virtue (a pietist subject is even described as a ‘virtuouso’ aspirant). Is it then simply that it was Rizvi’s profanities, and lack of aesthetics and middle-class politesse, that disqualified him as the virtuoso teacher and made him the inconvenient maulvi, instead?

The left-leaners who do real politics understand this but make a fetish of Rizvi’s appeal to the working classes with no evidence of his commitment to a single class-based issue or delivery of material rights. They would not credit the PPP or ANP for this even though, they do receive class-conscious votes. Is it leadership and following, not agenda that determines class identity? In which case, our left political leadership needs to seriously rethink its own composition.

How long before we reconcile that the working classes are not just non-liberal victims but can have liberal and/or secular aspirations too? And that many can be politically motivated bigots and misogynists. Instead of some misplaced infantilising calls to respect and indulge this for its decolonising potential, or pray for divine intervention, it is time for progressives to challenge such politics and be consistent in doing so. Otherwise, we can just wait for what will be the next charismatic virtuoso teacher for some, and the unclean inconvenient mullah for others but the base contradictions will continue to haunt us.