When I was an undergraduate at Rutgers University involved in my own mini-struggle against the campus’ Islamic society, my closest friends, Maryah Abbas and Anthony Aschettino, bought me the book ‘Ataturk’ by Andrew Mango. Reading it thrilled me to no end. Here was a hero from the Muslim World who had awakened a Muslim nation and brought it kicking and screaming to the modern world.

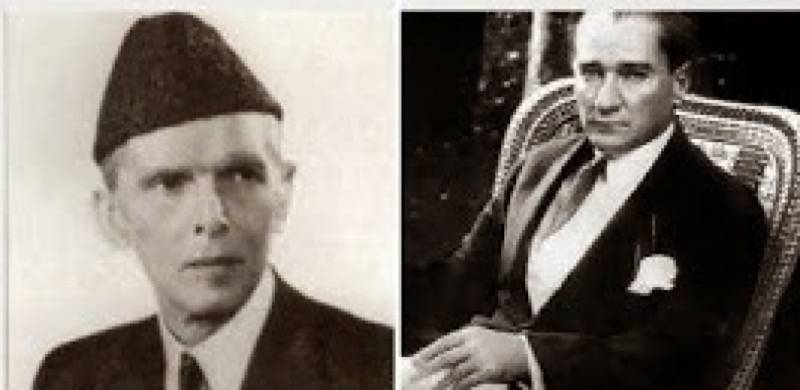

I had already found out through Hector Bolitho’s ‘Jinnah the Creator of Pakistan’ and Stanley Wolpert’s ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’ that Pakistan’s founding father, the parliamentary democrat and Anglicised barrister who spent his life using constitutional means to forward the cause of self-rule in India, had a turning point when he came across Grey Wolf by HC Armstrong, the controversial biography of Kemal Ataturk, while walking back from his Chambers on King’s Bench Walk. Arguably it was here that Jinnah moved towards the idea of modernising the Muslims, marking an end to his life long struggle as the ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity. Other than telling his daughter to call him Grey Wolf, Jinnah told his sister that he wanted to be the Indian Ataturk, something he would go on to repeat to a Sikh gathering in the aftermath of the Shaheed Ganj Mosque controversy in Lahore which he had helped resolve. He told his audience though that unlike Kemal he only had words and the law to fight his battle. The paradox is that Kemal Ataturk, the dictator of Turkey, should inspire a man like Jinnah steeped in British liberal tradition of Disraeli and Gladstone and an English Barrister to boot. A more apt inspiration from the Muslim World for Jinnah would have been Midhet Pasha of the Ottoman Empire, the father of Constitutional Monarchy of the late 19th Century, or Zaghlul Pasha of Egypt but nonetheless it was Kemal Ataturk who caught Jinnah’s fancy.

Ataturk’s narrow Turkish Nationalism based on former Muslim ruling class of the Ottoman Empire had devastating consequences for the formerly multicultural nature of the Ottoman Empire based on a neat consociationalism making coexistence between communities of that Empire possible. Nevertheless, Jinnah went on to describe Ataturk as the greatest man of the age and an example for Muslims of India in his eulogy in 1938. Jinnah saw a shadow of himself in Ataturk because both men were inspired by the western civilisation, albeit different ones. Jinnah had been inspired by the British legal tradition with its lower case secularism, an absence of ideology, while Ataturk admired the French model of Laicism or upper case Secularism as a state ideology.

Both Ataturk and Jinnah were accused of having used religion for their eventual ends, but we find that Ataturk’s use was much more brazen in ideological militaristic terms with cries of Jihad and Islam in danger, which we do not find in Jinnah’s lexicon. From 1924 to 1928, Turkey was the first Muslim Republic to have a state religion clause in its constitution, which was finally unceremoniously dropped in 1928 because that had been Ataturk’s ambition all along i.e. modernise the Turk nation and by Turk nation he meant one ethnicity, one language and one religion. By way of comparison it was only the third Pakistani constitution in 1973 that introduced a state religion. The framers of both 1956 and 1962 constitutions had firmly decided not to have a state religion in Pakistan. As much as one admires Ataturk and rightly so for his modernisation of Turkey, some parts of his legacy were deeply problematic. Tragically Kemalism was built on religious exclusion and while personally an atheist, as he would later tell an interviewer, Ataturk’s cynical use of Islam is obvious to anyone who has studied his life. He was given to taking the pulpit and declaring that Islam was the most rational religion as he did so during the famous Izmit (not to be confused with Izmir) Khutba in 1919, before the leading the faithful in prayer. Turkey, while a secular republic, continued to consolidate as a Hanafi Sunni ethnically Turkish state. Ataturk wanted to Turkify Islam and not jettison it altogether. In his overzealous Turkification, the “Non-Muslim” names such as Symrna were changed to Turkish names. This was inspired by the ideology of Mehmet Ziya Gokalp, Turkey’s equivalent of Allama Iqbal and Ataturk’s ally, as expressed in his famous book Principles of Turkism. Like Iqbal, Gokalp was inspired by Nietzsche and spoke of Turks as supermen. Turkification required a homogenous nation based on Turkish language and Hanafi Islam. The ideology of Turkification explains Ataturk’s efforts to produce a Quran entirely in the Turkish language and decree that Azaan or call to prayer would be in the Turkish language. Secular Turkey never quite abandoned the state religion because the Ministry of Religious Affairs has since 1928 held to the position that Hanafi Sunni Islam is the basic principle of Turkish Nationalism. In the famous six-day speech in1928 Ataturk explained his use of religion as a tactic because he could not have gotten the unflinching loyalty of his followers who could not understand his modernist secular vision at that moment. Overnight Ataturk changed Turkey into a modern republic based on his six principles: Republicanism, Populism, Nationalism, Laicism, Statism and Reformism. These were aimed at the uplift of Turk Hanafi Muslims i.e. the “nation”.

Most of Turkey’s Greek and other Non-Muslim populations had already been exchanged with Muslims in Greece through the treaty of Lausanne. In 1932 the Grand National Assembly moved to exclude all Non-Muslims from lucrative professions such as law etc. Prior to this these professions were held by Non-Muslims and Ataturk wanted to uplift the Muslim Turks who had remained backward making Turkey the sick man of Europe. Ataturk and the Turkish nationalist elite saw Non-Muslims as the fifth columnists of imperialist powers such as Britain and France. In 1934, the result of Ataturk’s controversial sun language theory, the resettlement law aimed at Jews, Christians, Kurds and Circassians was promulgated which sought to homogenisation of Turkish nation under the slogan one ethnicity, one religion and one language. This homogeneity meant that the Non-Muslim population of Turkey fell from 15 percent to only 1.3 percent in 1926. Today the percentage is only .002 percent. Turkification was complete under Ataturk but Erdogan today is undoing Ataturk’s secular reforms as well. The absence of Non-Muslims in Turkey has finally come to claim its pound of flesh from Ataturk’s Republic. Such is the tragedy of exclusivist nation states. The walk from King’s Bench walk in 1933 had fateful consequences for the subcontinent. Gokalp and Iqbal live on and the secular liberal ideas of men like Ataturk and Jinnah are abandoned sooner or later.

I had already found out through Hector Bolitho’s ‘Jinnah the Creator of Pakistan’ and Stanley Wolpert’s ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’ that Pakistan’s founding father, the parliamentary democrat and Anglicised barrister who spent his life using constitutional means to forward the cause of self-rule in India, had a turning point when he came across Grey Wolf by HC Armstrong, the controversial biography of Kemal Ataturk, while walking back from his Chambers on King’s Bench Walk. Arguably it was here that Jinnah moved towards the idea of modernising the Muslims, marking an end to his life long struggle as the ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity. Other than telling his daughter to call him Grey Wolf, Jinnah told his sister that he wanted to be the Indian Ataturk, something he would go on to repeat to a Sikh gathering in the aftermath of the Shaheed Ganj Mosque controversy in Lahore which he had helped resolve. He told his audience though that unlike Kemal he only had words and the law to fight his battle. The paradox is that Kemal Ataturk, the dictator of Turkey, should inspire a man like Jinnah steeped in British liberal tradition of Disraeli and Gladstone and an English Barrister to boot. A more apt inspiration from the Muslim World for Jinnah would have been Midhet Pasha of the Ottoman Empire, the father of Constitutional Monarchy of the late 19th Century, or Zaghlul Pasha of Egypt but nonetheless it was Kemal Ataturk who caught Jinnah’s fancy.

Ataturk’s narrow Turkish Nationalism based on former Muslim ruling class of the Ottoman Empire had devastating consequences for the formerly multicultural nature of the Ottoman Empire based on a neat consociationalism making coexistence between communities of that Empire possible. Nevertheless, Jinnah went on to describe Ataturk as the greatest man of the age and an example for Muslims of India in his eulogy in 1938. Jinnah saw a shadow of himself in Ataturk because both men were inspired by the western civilisation, albeit different ones. Jinnah had been inspired by the British legal tradition with its lower case secularism, an absence of ideology, while Ataturk admired the French model of Laicism or upper case Secularism as a state ideology.

Both Ataturk and Jinnah were accused of having used religion for their eventual ends, but we find that Ataturk’s use was much more brazen in ideological militaristic terms with cries of Jihad and Islam in danger, which we do not find in Jinnah’s lexicon. From 1924 to 1928, Turkey was the first Muslim Republic to have a state religion clause in its constitution, which was finally unceremoniously dropped in 1928 because that had been Ataturk’s ambition all along i.e. modernise the Turk nation and by Turk nation he meant one ethnicity, one language and one religion. By way of comparison it was only the third Pakistani constitution in 1973 that introduced a state religion. The framers of both 1956 and 1962 constitutions had firmly decided not to have a state religion in Pakistan. As much as one admires Ataturk and rightly so for his modernisation of Turkey, some parts of his legacy were deeply problematic. Tragically Kemalism was built on religious exclusion and while personally an atheist, as he would later tell an interviewer, Ataturk’s cynical use of Islam is obvious to anyone who has studied his life. He was given to taking the pulpit and declaring that Islam was the most rational religion as he did so during the famous Izmit (not to be confused with Izmir) Khutba in 1919, before the leading the faithful in prayer. Turkey, while a secular republic, continued to consolidate as a Hanafi Sunni ethnically Turkish state. Ataturk wanted to Turkify Islam and not jettison it altogether. In his overzealous Turkification, the “Non-Muslim” names such as Symrna were changed to Turkish names. This was inspired by the ideology of Mehmet Ziya Gokalp, Turkey’s equivalent of Allama Iqbal and Ataturk’s ally, as expressed in his famous book Principles of Turkism. Like Iqbal, Gokalp was inspired by Nietzsche and spoke of Turks as supermen. Turkification required a homogenous nation based on Turkish language and Hanafi Islam. The ideology of Turkification explains Ataturk’s efforts to produce a Quran entirely in the Turkish language and decree that Azaan or call to prayer would be in the Turkish language. Secular Turkey never quite abandoned the state religion because the Ministry of Religious Affairs has since 1928 held to the position that Hanafi Sunni Islam is the basic principle of Turkish Nationalism. In the famous six-day speech in1928 Ataturk explained his use of religion as a tactic because he could not have gotten the unflinching loyalty of his followers who could not understand his modernist secular vision at that moment. Overnight Ataturk changed Turkey into a modern republic based on his six principles: Republicanism, Populism, Nationalism, Laicism, Statism and Reformism. These were aimed at the uplift of Turk Hanafi Muslims i.e. the “nation”.

Most of Turkey’s Greek and other Non-Muslim populations had already been exchanged with Muslims in Greece through the treaty of Lausanne. In 1932 the Grand National Assembly moved to exclude all Non-Muslims from lucrative professions such as law etc. Prior to this these professions were held by Non-Muslims and Ataturk wanted to uplift the Muslim Turks who had remained backward making Turkey the sick man of Europe. Ataturk and the Turkish nationalist elite saw Non-Muslims as the fifth columnists of imperialist powers such as Britain and France. In 1934, the result of Ataturk’s controversial sun language theory, the resettlement law aimed at Jews, Christians, Kurds and Circassians was promulgated which sought to homogenisation of Turkish nation under the slogan one ethnicity, one religion and one language. This homogeneity meant that the Non-Muslim population of Turkey fell from 15 percent to only 1.3 percent in 1926. Today the percentage is only .002 percent. Turkification was complete under Ataturk but Erdogan today is undoing Ataturk’s secular reforms as well. The absence of Non-Muslims in Turkey has finally come to claim its pound of flesh from Ataturk’s Republic. Such is the tragedy of exclusivist nation states. The walk from King’s Bench walk in 1933 had fateful consequences for the subcontinent. Gokalp and Iqbal live on and the secular liberal ideas of men like Ataturk and Jinnah are abandoned sooner or later.