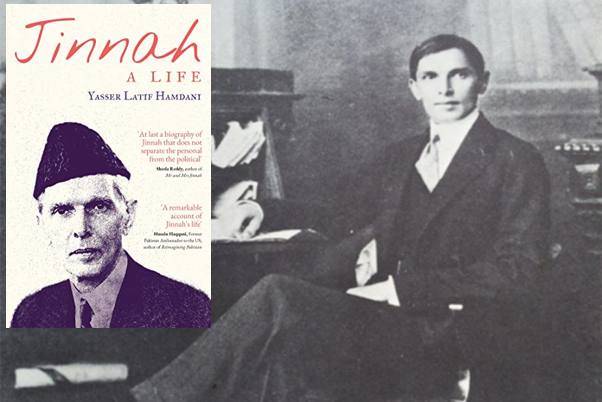

Jinnah comes alive in Hamdani’s biography, “Jinnah: A Life.” Jinnah was a lawyer turned politician who early in his career was hailed as an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. Later in life, he came to believe that Muslims and Hindus were two nations.

There have been many biographies of the man who is remembered by history as the founder of Pakistan. Hamdani’s is bound to stand out. It’s neither a hagiography nor a damnation. It’s an honest appraisal of the man who later would be venerated as the Quaid-e-Azam by millions.

Once Jinnah had concluded that Indian Muslims would be dominated by a permanent Hindu majority, he began to canvass support for his position among conservative British politicians. Hamdani says that “Jinnah found an ally in Winston Churchill, who found himself in congruence with the idea of Pakistan. Jinnah and Churchill seem to have spent a lot of time together on Churchill’s estate.”

Even then, as Hamdani notes, Jinnah did not want to create a Pakistan divorced from the rest of India. He had envisaged Pakistan and Hindustan would be part of an Indian Union. He writes, “Pakistan would act as countervailing force to any overbearing center dominated by what Jinnah called the caste Hindu majority….The so-called triumph of his life, the crowning glory of his political career, if biographers and historians are to be believed, was thus imposed on him through an act of bullying on part of Mountbatten.”

Hamdani recounts Jinnah’s emotions as he flew out of Delhi on the 7th of August, 1947 bound for Karachi. He expressed the hope that the past would be buried and stated, “Let us start afresh as two independent sovereign states of Hindustan and Pakistan.”

As he landed in Karachi, Hamdani says, his sister, Fatima, “excitedly remarked on how many people had gathered to receive them….Jinnah did not show any exhilaration or excitement. After all, this marked the end of another dream, even if it was a beginning for Pakistan. The dream that Jinnah had dedicated most of his life to, the dream of a united India had now come to an end.”

Once Pakistan was created, Jinnah assumed the position of Governor General. Several things happened during his brief stay in power. One was the invasion of Kashmir by tribesman who had been armed by the Pakistani army. Did Jinnah authorize the invasion?

Hamdani says, no, “Jinnah was entirely ignorant of the tribal invasion till at least October 10, 1947, when it was officially underway in the north.” Hamdani cites Jinnah’s sister’s opinion that Jinnah was ‘very sorry that a thoughtless step had been taken in such a crude and unorganized manner.’”

Did Jinnah have any interest in military matters? Hamdani, citing Stephen Cohen, says that “Jinnah had no interest in military matters beyond a political angle…Jinnah believed that policy had to be made by civilians and that had military had no role in politics.”

Pakistan was created as a homeland for the Muslims of British India but Jinnah never intended it to be religious state, much less a theocracy. Hamdani cites his August 11, 1947 speech in which Jinnah decided to “bury the Two Nation Theory” which had been the genesis for creating the country. It had served its purpose. Pakistan was now a reality. It would function as a parliamentary democracy, a secular state, in which Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Hindus and Muslims in the public sense of the word. They would all be equal citizens of Pakistan.

Hamdani quotes from Jinnah’s speech at a Parsi gathering in Karachi in February 1948: “I assure you, Pakistan means to stand by its oft repeated promises of equal rights to all its minorities, irrespective of their caste or creed.” Hamdani, quoting Oxford scholar Faisal Devji, says that “Jinnah had sought to ‘secularize Islam by making belief and practice entirely nominal.’”

Hamdani points out that not even once did Jinnah conceive that Pakistan would be a religious state. He opposed the Khilafat movement in British India which sought to return the Ottoman caliphate to power in Turkey. Jinnah was, in fact, an admirer of the secular leader who came after the demise of the Ottomans, Kemal Ataturk.

In September 1948, Jinnah was ailing with multiple pulmonary ailments. He knew the end was near. Reflecting on the tumultuous events that had transpired since the creation of Pakistan, Hamdani says, “Jinnah told his doctor that Pakistan had been the biggest blunder of his life and that he wanted to go to Delhi and tell Jawaharlal Nehru to be friend again.”

Perhaps he saw what in store for Pakistan. Within a decade of his death, Pakistan turned into an authoritarian state that would henceforth be governed explicitly or implicitly by a string of army chiefs. Each military dictator sought to wash his sins by sitting underneath Jinnah’s portrait and paying lip service to the founder’s vision. Each coup maker sought to divert attention by seeking to wrest Kashmir from India through military action but failed to do so.

The first one, Ayub Khan, neglected the development of the Eastern province where a majority of Pakistanis lived. In 1971, under the bumbled rule of his successor general, Yahya, the East broke away. This was inevitable since Yahya had annulled the results of a general election which was won by the largest party in the East, precipitating a Civil War which turned into to a war with India.

After the secession of East Pakistan the state became even more insecure. The issue was no longer Kashmir. It was the survival of what remained of Pakistan. Religion entered the body language, destined never to leave. Even the secular Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a sworn socialist who frequently wore the Mao cap, joined hands with the Jamaat-e-Islami, a party that had opposed the creation of Pakistan, to declare the Ahmadis, a minority sect, as non-Muslims.

Nuclear weapons were developed to prevent an Indian invasion. Years later, Blasphemy Laws would be invoked to incite mobs against anyone suspected of violating the basic tenets of the faith.

Hamdani notes, Pakistan and India traversed a path of mutual hostility that Jinnah would never have wanted. He wonders what Jinnah “would have thought of the terrorist attack on his favorite city in the subcontinent and especially on the Taj Mahal hotel, with which he had a personal relationship of a very intimate kind.”

The book sheds light on Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan but it does not tell you why Pakistan deviated from Jinnah’s vision. Perhaps that could be the author’s next book.

There have been many biographies of the man who is remembered by history as the founder of Pakistan. Hamdani’s is bound to stand out. It’s neither a hagiography nor a damnation. It’s an honest appraisal of the man who later would be venerated as the Quaid-e-Azam by millions.

Once Jinnah had concluded that Indian Muslims would be dominated by a permanent Hindu majority, he began to canvass support for his position among conservative British politicians. Hamdani says that “Jinnah found an ally in Winston Churchill, who found himself in congruence with the idea of Pakistan. Jinnah and Churchill seem to have spent a lot of time together on Churchill’s estate.”

Even then, as Hamdani notes, Jinnah did not want to create a Pakistan divorced from the rest of India. He had envisaged Pakistan and Hindustan would be part of an Indian Union. He writes, “Pakistan would act as countervailing force to any overbearing center dominated by what Jinnah called the caste Hindu majority….The so-called triumph of his life, the crowning glory of his political career, if biographers and historians are to be believed, was thus imposed on him through an act of bullying on part of Mountbatten.”

Hamdani recounts Jinnah’s emotions as he flew out of Delhi on the 7th of August, 1947 bound for Karachi. He expressed the hope that the past would be buried and stated, “Let us start afresh as two independent sovereign states of Hindustan and Pakistan.”

As he landed in Karachi, Hamdani says, his sister, Fatima, “excitedly remarked on how many people had gathered to receive them….Jinnah did not show any exhilaration or excitement. After all, this marked the end of another dream, even if it was a beginning for Pakistan. The dream that Jinnah had dedicated most of his life to, the dream of a united India had now come to an end.”

Once Pakistan was created, Jinnah assumed the position of Governor General. Several things happened during his brief stay in power. One was the invasion of Kashmir by tribesman who had been armed by the Pakistani army. Did Jinnah authorize the invasion?

Hamdani says, no, “Jinnah was entirely ignorant of the tribal invasion till at least October 10, 1947, when it was officially underway in the north.” Hamdani cites Jinnah’s sister’s opinion that Jinnah was ‘very sorry that a thoughtless step had been taken in such a crude and unorganized manner.’”

Did Jinnah have any interest in military matters? Hamdani, citing Stephen Cohen, says that “Jinnah had no interest in military matters beyond a political angle…Jinnah believed that policy had to be made by civilians and that had military had no role in politics.”

Pakistan was created as a homeland for the Muslims of British India but Jinnah never intended it to be religious state, much less a theocracy. Hamdani cites his August 11, 1947 speech in which Jinnah decided to “bury the Two Nation Theory” which had been the genesis for creating the country. It had served its purpose. Pakistan was now a reality. It would function as a parliamentary democracy, a secular state, in which Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Hindus and Muslims in the public sense of the word. They would all be equal citizens of Pakistan.

Hamdani quotes from Jinnah’s speech at a Parsi gathering in Karachi in February 1948: “I assure you, Pakistan means to stand by its oft repeated promises of equal rights to all its minorities, irrespective of their caste or creed.” Hamdani, quoting Oxford scholar Faisal Devji, says that “Jinnah had sought to ‘secularize Islam by making belief and practice entirely nominal.’”

Hamdani points out that not even once did Jinnah conceive that Pakistan would be a religious state. He opposed the Khilafat movement in British India which sought to return the Ottoman caliphate to power in Turkey. Jinnah was, in fact, an admirer of the secular leader who came after the demise of the Ottomans, Kemal Ataturk.

In September 1948, Jinnah was ailing with multiple pulmonary ailments. He knew the end was near. Reflecting on the tumultuous events that had transpired since the creation of Pakistan, Hamdani says, “Jinnah told his doctor that Pakistan had been the biggest blunder of his life and that he wanted to go to Delhi and tell Jawaharlal Nehru to be friend again.”

Perhaps he saw what in store for Pakistan. Within a decade of his death, Pakistan turned into an authoritarian state that would henceforth be governed explicitly or implicitly by a string of army chiefs. Each military dictator sought to wash his sins by sitting underneath Jinnah’s portrait and paying lip service to the founder’s vision. Each coup maker sought to divert attention by seeking to wrest Kashmir from India through military action but failed to do so.

The first one, Ayub Khan, neglected the development of the Eastern province where a majority of Pakistanis lived. In 1971, under the bumbled rule of his successor general, Yahya, the East broke away. This was inevitable since Yahya had annulled the results of a general election which was won by the largest party in the East, precipitating a Civil War which turned into to a war with India.

After the secession of East Pakistan the state became even more insecure. The issue was no longer Kashmir. It was the survival of what remained of Pakistan. Religion entered the body language, destined never to leave. Even the secular Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a sworn socialist who frequently wore the Mao cap, joined hands with the Jamaat-e-Islami, a party that had opposed the creation of Pakistan, to declare the Ahmadis, a minority sect, as non-Muslims.

Nuclear weapons were developed to prevent an Indian invasion. Years later, Blasphemy Laws would be invoked to incite mobs against anyone suspected of violating the basic tenets of the faith.

Hamdani notes, Pakistan and India traversed a path of mutual hostility that Jinnah would never have wanted. He wonders what Jinnah “would have thought of the terrorist attack on his favorite city in the subcontinent and especially on the Taj Mahal hotel, with which he had a personal relationship of a very intimate kind.”

The book sheds light on Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan but it does not tell you why Pakistan deviated from Jinnah’s vision. Perhaps that could be the author’s next book.