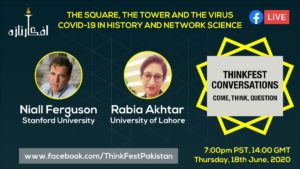

Last week, a group of Pakistani scholars and activists sparred in an extended online debate over the Thinkfest committee’s decision to host historian, Niall Ferguson on their webinar series. He was in dialogue with Professor Rabia Akhtar on his recent book on networks and power. The debate between the objectors to Ferguson’s views[1] and the organisers condensed into the legal and ethical dimensions of free speech – a matter that is best left for legal minds to unpack. But there were other issues that revealed some repeat contradictions espoused by those who would identify as scholar-activists and it’s important to recall and untangle them too.

Conspicuously absent in the social media exchanges above was the class-based nature of these events that are now called ‘festivals’ and the contradictory and selective practice of deplatforming or cancelling that they have inspired over the years. For over a decade and half, I have observed and commented on the politics of festivals, summarised below for context.

Deradicalising festivals

I first wrote about the politics of cultural patronage in 2006 when Gen Musharraf’s regime was sponsoring art festivals, Sufi conferences, and fashion shows which were inviting him to their ceremonies such as, at the Kara film festival (The News, 13th Dec.). My column offended some progressives who even wrote letters to the editor objecting to my claim that this was an endorsement of Gen Musharraf’s ‘enlightened moderation’ posturing, as a ‘personal attack’. Ironically, last week, many of these same progressives supported the deplatforming of Ferguson, arguing that it was ‘tone-deaf’ to privilege his views at a time of the Black Lives Matter protests. Strangely, endorsing a military usurper’s bid for legitimacy is more acceptable than inviting an individual academic with whom one holds intellectual differences.

In 2009, I pointed out the insincerity of many PPP loyalists who attempted to justify the trashing of the Shinakht culture festival in Karachi for carrying a painting of Benazir Bhutto positioned in the lap of Gen Zia ul Haq, by calling it an act of ‘political blasphemy’. At the time, the organisers at the Citizens Archive refused to condemn this censorship. In 2019, this was repeated by the organisers of the Karachi Biennale, who disassociated themselves with the ‘Killing Fields of Karachi’ exhibit – an artistic protest of the extra judicial killings led by Rao Anwar - when it was destroyed and removed by law enforcement authorities. On the one hand, these events pose as alternative cultural sites for freedoms of expression but at the first challenge, cave in and justify censorship.

Similarly, I found the thematic fashion shows that were promoted as acts of ‘resistance’ to terrorism at the peak of military operations in the tribal areas in 2009, to be absurd nationalist masquerades that lent a liberal cover to military establishment’s double game (The News, Oct 2009). Many defended this as an important symbol of liberal resistance but refused to acknowledge the cost of such abstract concessions.

As expected, this trend then morphed into ‘festivals for a cause’ with the Karachi Literature Festivals organised by the Oxford University Press (Pakistan) in 2010. In 2014, I wrote on the fallacy of repeat festivals that offered themselves as some counter-terrorism cultural resistance and the sponsorship that drove their repetitive reductive content as a literal, ‘supermarket of ideas’. Many academics and activists who otherwise career against such capitalist and NGO-style politics, have participated enthusiastically in these festivals. Many did not have any book or published work but simply moderated – a profession in itself. It rings of hollow sanctimony when many of these same scholar-activists rejected Ferguson’s talk as part of the ‘liberal’ notion of the ‘supermarket of ideas’ when they have been participating in events which are literally, a potpourri of half-baked ideas.

Finally, since gender is such a timely cash-cow, the British Council introduced its ‘WOW’ festivals in Pakistan in 2016. The first one was held on 1st May, the ideological marker of Labour Day, and boasted many of our prominent socialists and feminists under the banners of L’Oreal, Standard Chartered Bank, and Lost Ironies. Some activist-journalists who were outraged at the Thinkfest’s decision to host an academic of apologist colonialist views, had in 2016 exercised skillful sleight of hand and at the last minute, pulled a co-authored article that protested WOW’s total co-optation of resistance activism. Is deplatforming a selective right, reserved only for those with woke discretionary powers to exercise this?

The Afkar e Taza Thinkfest started in 2017 as an academic conference for scholars to share their published works. It has since expanded to including non-academicians and after appointing a committee (including non-academics) to govern, it has started leaning towards the usual celebrity-studded festivals and solicits (local) private sector sponsorship. Notable however, is that Thinkfest 2020 hosted scholar-activist Ammar Jan despite the ‘controversies’ associated with him which had led to his being ‘deplatformed’ by other prior festivals.

The Afkar e Taza Thinkfest started in 2017 as an academic conference for scholars to share their published works. It has since expanded to including non-academicians and after appointing a committee (including non-academics) to govern, it has started leaning towards the usual celebrity-studded festivals and solicits (local) private sector sponsorship. Notable however, is that Thinkfest 2020 hosted scholar-activist Ammar Jan despite the ‘controversies’ associated with him which had led to his being ‘deplatformed’ by other prior festivals.

Rather than detailing the specifics of the debate observed over the Ferguson exchange, I simply situate the above contradictions to show how these were replayed in this instance.

Principle contradictions

The first constant is that anxieties over representation within the scholar-activist community remains largely, a Punjab centric worry. Although there is denial that there was any gang-busting of Ferguson’s talk, it was almost exclusively a group of LUMS scholars who launched the objections to the Thinkfest session in various twitter threads and by tagging each other.

Since it is primarily a business university, there are several centres/schools at LUMS that are sponsored and named after industrialists or multinational products themselves. This is not uncommon to universities around the world and is a usual feature of neoliberal academia. Faculty members at LUMS do not decide on administrative tasks of naming or sourcing sponsorship but surely, such intimate paradoxes should counsel their calls for others to deplatform, cancel, or for internal decolonisation. At the very least, it should invite some simultaneous introspection.

The issue of structural changes and challenges becomes more concerning when call outs by students of LUMS on sexual harassment, bias, bigotry, wage injustices, gate-keeping and nepotism proliferate online. The same vigilant faculty members who are so passionate about the flaws of other organisations tend not to devote their online attention to long dialogues or debate on these matters, beyond some sympathetic retweets. Some balance and re-prioritisation of scholar-activists’ attention may be beneficial here.

Malala has been the most conspicuous target of the politics of cancellation when many in Pakistan actually deplatformed[2] her for winning the Nobel peace prize. Similarly, groups have called out select Pakistani NGOs and women’s rights activists for their collaboration with and as award recipients from Western governments (but not those who have received awards from military rulers).

In 2012, LUMS hosted alumna and foreign minister, Hina Rabbani Khar to speak at a time when her government was complicit in regular drone-warfare in the tribal areas– an issue over which many students were otherwise devoting their considerable activist energies. There is no record of deplatforming or cancellation activism over this.

When self-identified Muslim-British politician Baronness Syeda Warsi was invited to speak at Fatima Jinnah University in 2010, there were no calls for deplatforming or cancelling her. For all Warsi’s admirable achievements as a brown woman who rose the political ranks in Britain, she was a member of and represented a zealous neocon political party that cheers on wars, the monarchy, and colonialism and doesn’t just host race apologists but has produced leaders such as PM Boris Johnson who famously likened veiled Muslim women to “letter boxes”.

Do personalities have to be incontrovertible in their field to qualify as speakers? If the rationale for deplatforming is that there is no need to encourage hegemonic powerful narratives, then should we cancel any speaker or talk on Islamophobia in Muslim-majoritarian contexts?

A second point of contradiction has serious risk implications. Many scholar-activists conduct no fact-checking before jumping on to the woke bandwagon of any particular media-worthy case. Their support is based on the reputation of the lawyers or offending parties involved. If a right-wing cleric registers a case of blasphemy, it is assumed that the cleric is always wrong and is ‘abusing’ the law as a tool. There are no codes of conduct for activists or for hashtag campaigns which can have serious legal and life-affecting implications. Instead of standing up for the principle of the right to free speech and academic freedoms, progressive supporters hide behind the defense that their selected victim never said anything incriminatory.

Sacrificing the principle of free speech or applying it selectively can end up strengthening contradictions. Some activists sympathise with Muslims in the west who are offended by acts of blasphemy as part of the trope of Islamophobia. But for Pakistan, they object to the laws, as if no-one can ever commit blasphemy or that those claiming offense could be genuinely offended.

Additionally, there are those scholar-activists who consider themselves to be exceptionally radical and who reductively object to “liberal freedoms” and often preach on how the “liberals” must engage and dialogue with the right wing/Islamists so that no binaries remain. This is a tiresome and hollow solipsism. These very same ‘radicals’ will selectively support the most ‘liberal’ of causes when it suits them, such as, the anti-death penalty campaign, or for individualistic liberal sexual freedoms, despite the clear challenge these offer to settled religious edicts or the majoritarian collective ethos. They have also never held a single dialogue or engagement with the right wing beyond those for their dissertation purposes.

Too many scholar-activists prescribe what others should do and claim permanent injury for themselves. Social media allegations and call outs often do not offer evidence for their experiences. In cases of harassment and bullying this is understandable but genuine claims of victimisation are undermined when any critique of published scholarship is declared as an injurious “ad hominem attack”. Criminally, scholar-friends won’t even do the basic search to confirm if the allegations of being attacked are accurate or ask for evidence but instead, heart and retweet the same angst publicly until it becomes a given.

Many involved in the Ferguson debate had not read his works and some had only read the critiques but not the original works. I’ve read both when they first were published and did not need to reference his marriage or career to decide what I thought of these. I still listened in to the Thinkfest session because the host was a Pakistani woman scholar and my interest lay in that, rather than personalised speculation that she was some state spokesperson worthy of cancellation too. Listening inspired newer disagreement and counterpoints to Ferguson’s scholarship.

Build the platform before deplatforming

We can agree that scholars are no moral angels and all of us at some point disagree or even mock each other, even in a personalised manner over private discussions. But to issue publicised call outs in the same manner suggests a more malafide, self-promotional, and self-righteous purpose. Objections to tone and vocabulary are also selective; when friends are at the receiving end, then snark and scorn are considered personalised and toxic but; when non-friends are involved, the same take-downs are dismissed as mere humour and clever satire which need not be termed smear politics.

Contradictions catch up when principles are applied selectively. Personal and political contradictions are occupational hazards that activists constantly navigate (particularly class-based ones) but maintaining core principles and adhering to these consistently along some ideological alignment helps to minimise intellectual bankruptcy.

The other very important built-in corrective for activism is when it is guided by the wisdom of a collective, rather than bonding in institutional loyalty, or behaving as groupies or fan boys and girls who fawn in publicised sycophancy.

Contrary to what some scholars have argued, nothing within academic disciplines is a “settled” question, time period, or completed business. The argument that there is a ‘supermarket of ideas’ in American academia but a single hegemonic narrative dominates in Pakistan and so speakers like Ferguson are dangerous, is counter-intuitive. The narrative on colonialism in Pakistan is jingoistic and nationalistic - not nuanced, gendered, in- or con-clusive, at all. This does not justify glorification or glossed history writing but the premise is dangerous that the time has come for only consuming corrective history. This comes too close to the BJP’s historical revisionism project.

As a teacher it perturbs me greatly to hear students receiving over-deterministic critiques of modernity in our universities today with no problematising of the questions of gender, class, slavery or minorities. To think that postmodern studies is the ‘settled’ prescribed route to woke teaching is deeply disconcerting. Pretending that liberalism, secularism and human rights are neocolonial western baggage (but not feminism or socialism) that have wholesale blanketed Pakistan and are practiced as consistent handmaidens to capitalism in the same way as they are in the West is a disingenuous, limited and self-issued verdict that echoes in the chamber of social media. Pettier still, is the argument from the right but also some immature left aspirants, that if one espouses feminism or secularism then one is either betrayer of Islam or a dupe of western enlightenment.

Instead of insisting on arbitrary deplatforming and cancelling on the basis of social likes and professional loyalties, it may serve scholar-activists to first build a mutually respectful platform for intellectual exchange. The parameters of debate and conduct can be mutually agreed upon and some basic principles recognised, provided these are not arbitrary, selective or quickly sacrificed to egos, personalised competitiveness or point-scoring. After that, let rigorous and robust debates and disagreements build within the boundaries of informed respect and through methods of inquiry that expand outward and include those we disagree with, rather than following narrow, parochial and self-contradictory paths.

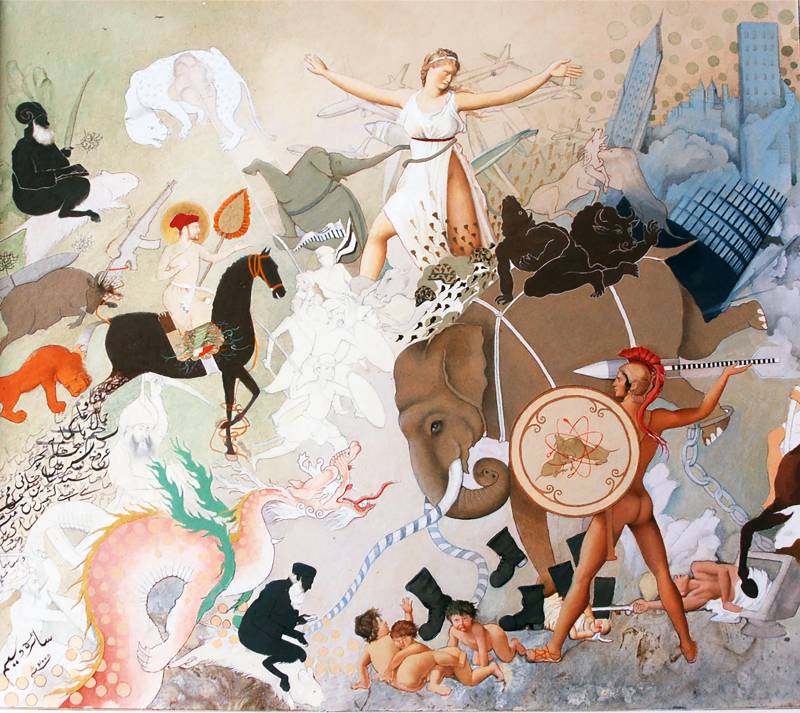

(Image above: Painting by Saira Wasim, Please For Peace, 2008. Gouache, gold leaf, marbling and ink on wasli paper. 21.5 x 22.8 inches.)

[1] The descriptions of him ranged from elitist colonial apologist to, a racist and Islamophobic layman.

[2] The All Pakistan Private Schools Management Association and The All Pakistan Private Schools Federation (which included ‘English-medium’ schools, considered to be bastions of “liberal thinking”) banned Malala’s autobiography in all their affiliate schools and their libraries. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/inspiration-or-danger-private-schools-in-pakistan-ban-malala-yousafzais-book-8930925.html. Public events around her book were attacked and shut down.

Conspicuously absent in the social media exchanges above was the class-based nature of these events that are now called ‘festivals’ and the contradictory and selective practice of deplatforming or cancelling that they have inspired over the years. For over a decade and half, I have observed and commented on the politics of festivals, summarised below for context.

Deradicalising festivals

I first wrote about the politics of cultural patronage in 2006 when Gen Musharraf’s regime was sponsoring art festivals, Sufi conferences, and fashion shows which were inviting him to their ceremonies such as, at the Kara film festival (The News, 13th Dec.). My column offended some progressives who even wrote letters to the editor objecting to my claim that this was an endorsement of Gen Musharraf’s ‘enlightened moderation’ posturing, as a ‘personal attack’. Ironically, last week, many of these same progressives supported the deplatforming of Ferguson, arguing that it was ‘tone-deaf’ to privilege his views at a time of the Black Lives Matter protests. Strangely, endorsing a military usurper’s bid for legitimacy is more acceptable than inviting an individual academic with whom one holds intellectual differences.

In 2009, I pointed out the insincerity of many PPP loyalists who attempted to justify the trashing of the Shinakht culture festival in Karachi for carrying a painting of Benazir Bhutto positioned in the lap of Gen Zia ul Haq, by calling it an act of ‘political blasphemy’. At the time, the organisers at the Citizens Archive refused to condemn this censorship. In 2019, this was repeated by the organisers of the Karachi Biennale, who disassociated themselves with the ‘Killing Fields of Karachi’ exhibit – an artistic protest of the extra judicial killings led by Rao Anwar - when it was destroyed and removed by law enforcement authorities. On the one hand, these events pose as alternative cultural sites for freedoms of expression but at the first challenge, cave in and justify censorship.

Similarly, I found the thematic fashion shows that were promoted as acts of ‘resistance’ to terrorism at the peak of military operations in the tribal areas in 2009, to be absurd nationalist masquerades that lent a liberal cover to military establishment’s double game (The News, Oct 2009). Many defended this as an important symbol of liberal resistance but refused to acknowledge the cost of such abstract concessions.

As expected, this trend then morphed into ‘festivals for a cause’ with the Karachi Literature Festivals organised by the Oxford University Press (Pakistan) in 2010. In 2014, I wrote on the fallacy of repeat festivals that offered themselves as some counter-terrorism cultural resistance and the sponsorship that drove their repetitive reductive content as a literal, ‘supermarket of ideas’. Many academics and activists who otherwise career against such capitalist and NGO-style politics, have participated enthusiastically in these festivals. Many did not have any book or published work but simply moderated – a profession in itself. It rings of hollow sanctimony when many of these same scholar-activists rejected Ferguson’s talk as part of the ‘liberal’ notion of the ‘supermarket of ideas’ when they have been participating in events which are literally, a potpourri of half-baked ideas.

Finally, since gender is such a timely cash-cow, the British Council introduced its ‘WOW’ festivals in Pakistan in 2016. The first one was held on 1st May, the ideological marker of Labour Day, and boasted many of our prominent socialists and feminists under the banners of L’Oreal, Standard Chartered Bank, and Lost Ironies. Some activist-journalists who were outraged at the Thinkfest’s decision to host an academic of apologist colonialist views, had in 2016 exercised skillful sleight of hand and at the last minute, pulled a co-authored article that protested WOW’s total co-optation of resistance activism. Is deplatforming a selective right, reserved only for those with woke discretionary powers to exercise this?

The Afkar e Taza Thinkfest started in 2017 as an academic conference for scholars to share their published works. It has since expanded to including non-academicians and after appointing a committee (including non-academics) to govern, it has started leaning towards the usual celebrity-studded festivals and solicits (local) private sector sponsorship. Notable however, is that Thinkfest 2020 hosted scholar-activist Ammar Jan despite the ‘controversies’ associated with him which had led to his being ‘deplatformed’ by other prior festivals.

The Afkar e Taza Thinkfest started in 2017 as an academic conference for scholars to share their published works. It has since expanded to including non-academicians and after appointing a committee (including non-academics) to govern, it has started leaning towards the usual celebrity-studded festivals and solicits (local) private sector sponsorship. Notable however, is that Thinkfest 2020 hosted scholar-activist Ammar Jan despite the ‘controversies’ associated with him which had led to his being ‘deplatformed’ by other prior festivals.Rather than detailing the specifics of the debate observed over the Ferguson exchange, I simply situate the above contradictions to show how these were replayed in this instance.

Principle contradictions

The first constant is that anxieties over representation within the scholar-activist community remains largely, a Punjab centric worry. Although there is denial that there was any gang-busting of Ferguson’s talk, it was almost exclusively a group of LUMS scholars who launched the objections to the Thinkfest session in various twitter threads and by tagging each other.

Since it is primarily a business university, there are several centres/schools at LUMS that are sponsored and named after industrialists or multinational products themselves. This is not uncommon to universities around the world and is a usual feature of neoliberal academia. Faculty members at LUMS do not decide on administrative tasks of naming or sourcing sponsorship but surely, such intimate paradoxes should counsel their calls for others to deplatform, cancel, or for internal decolonisation. At the very least, it should invite some simultaneous introspection.

The issue of structural changes and challenges becomes more concerning when call outs by students of LUMS on sexual harassment, bias, bigotry, wage injustices, gate-keeping and nepotism proliferate online. The same vigilant faculty members who are so passionate about the flaws of other organisations tend not to devote their online attention to long dialogues or debate on these matters, beyond some sympathetic retweets. Some balance and re-prioritisation of scholar-activists’ attention may be beneficial here.

Malala has been the most conspicuous target of the politics of cancellation when many in Pakistan actually deplatformed[2] her for winning the Nobel peace prize. Similarly, groups have called out select Pakistani NGOs and women’s rights activists for their collaboration with and as award recipients from Western governments (but not those who have received awards from military rulers).

In 2012, LUMS hosted alumna and foreign minister, Hina Rabbani Khar to speak at a time when her government was complicit in regular drone-warfare in the tribal areas– an issue over which many students were otherwise devoting their considerable activist energies. There is no record of deplatforming or cancellation activism over this.

When self-identified Muslim-British politician Baronness Syeda Warsi was invited to speak at Fatima Jinnah University in 2010, there were no calls for deplatforming or cancelling her. For all Warsi’s admirable achievements as a brown woman who rose the political ranks in Britain, she was a member of and represented a zealous neocon political party that cheers on wars, the monarchy, and colonialism and doesn’t just host race apologists but has produced leaders such as PM Boris Johnson who famously likened veiled Muslim women to “letter boxes”.

Do personalities have to be incontrovertible in their field to qualify as speakers? If the rationale for deplatforming is that there is no need to encourage hegemonic powerful narratives, then should we cancel any speaker or talk on Islamophobia in Muslim-majoritarian contexts?

A second point of contradiction has serious risk implications. Many scholar-activists conduct no fact-checking before jumping on to the woke bandwagon of any particular media-worthy case. Their support is based on the reputation of the lawyers or offending parties involved. If a right-wing cleric registers a case of blasphemy, it is assumed that the cleric is always wrong and is ‘abusing’ the law as a tool. There are no codes of conduct for activists or for hashtag campaigns which can have serious legal and life-affecting implications. Instead of standing up for the principle of the right to free speech and academic freedoms, progressive supporters hide behind the defense that their selected victim never said anything incriminatory.

Sacrificing the principle of free speech or applying it selectively can end up strengthening contradictions. Some activists sympathise with Muslims in the west who are offended by acts of blasphemy as part of the trope of Islamophobia. But for Pakistan, they object to the laws, as if no-one can ever commit blasphemy or that those claiming offense could be genuinely offended.

Additionally, there are those scholar-activists who consider themselves to be exceptionally radical and who reductively object to “liberal freedoms” and often preach on how the “liberals” must engage and dialogue with the right wing/Islamists so that no binaries remain. This is a tiresome and hollow solipsism. These very same ‘radicals’ will selectively support the most ‘liberal’ of causes when it suits them, such as, the anti-death penalty campaign, or for individualistic liberal sexual freedoms, despite the clear challenge these offer to settled religious edicts or the majoritarian collective ethos. They have also never held a single dialogue or engagement with the right wing beyond those for their dissertation purposes.

Too many scholar-activists prescribe what others should do and claim permanent injury for themselves. Social media allegations and call outs often do not offer evidence for their experiences. In cases of harassment and bullying this is understandable but genuine claims of victimisation are undermined when any critique of published scholarship is declared as an injurious “ad hominem attack”. Criminally, scholar-friends won’t even do the basic search to confirm if the allegations of being attacked are accurate or ask for evidence but instead, heart and retweet the same angst publicly until it becomes a given.

Many involved in the Ferguson debate had not read his works and some had only read the critiques but not the original works. I’ve read both when they first were published and did not need to reference his marriage or career to decide what I thought of these. I still listened in to the Thinkfest session because the host was a Pakistani woman scholar and my interest lay in that, rather than personalised speculation that she was some state spokesperson worthy of cancellation too. Listening inspired newer disagreement and counterpoints to Ferguson’s scholarship.

Build the platform before deplatforming

We can agree that scholars are no moral angels and all of us at some point disagree or even mock each other, even in a personalised manner over private discussions. But to issue publicised call outs in the same manner suggests a more malafide, self-promotional, and self-righteous purpose. Objections to tone and vocabulary are also selective; when friends are at the receiving end, then snark and scorn are considered personalised and toxic but; when non-friends are involved, the same take-downs are dismissed as mere humour and clever satire which need not be termed smear politics.

Contradictions catch up when principles are applied selectively. Personal and political contradictions are occupational hazards that activists constantly navigate (particularly class-based ones) but maintaining core principles and adhering to these consistently along some ideological alignment helps to minimise intellectual bankruptcy.

The other very important built-in corrective for activism is when it is guided by the wisdom of a collective, rather than bonding in institutional loyalty, or behaving as groupies or fan boys and girls who fawn in publicised sycophancy.

Contrary to what some scholars have argued, nothing within academic disciplines is a “settled” question, time period, or completed business. The argument that there is a ‘supermarket of ideas’ in American academia but a single hegemonic narrative dominates in Pakistan and so speakers like Ferguson are dangerous, is counter-intuitive. The narrative on colonialism in Pakistan is jingoistic and nationalistic - not nuanced, gendered, in- or con-clusive, at all. This does not justify glorification or glossed history writing but the premise is dangerous that the time has come for only consuming corrective history. This comes too close to the BJP’s historical revisionism project.

As a teacher it perturbs me greatly to hear students receiving over-deterministic critiques of modernity in our universities today with no problematising of the questions of gender, class, slavery or minorities. To think that postmodern studies is the ‘settled’ prescribed route to woke teaching is deeply disconcerting. Pretending that liberalism, secularism and human rights are neocolonial western baggage (but not feminism or socialism) that have wholesale blanketed Pakistan and are practiced as consistent handmaidens to capitalism in the same way as they are in the West is a disingenuous, limited and self-issued verdict that echoes in the chamber of social media. Pettier still, is the argument from the right but also some immature left aspirants, that if one espouses feminism or secularism then one is either betrayer of Islam or a dupe of western enlightenment.

Instead of insisting on arbitrary deplatforming and cancelling on the basis of social likes and professional loyalties, it may serve scholar-activists to first build a mutually respectful platform for intellectual exchange. The parameters of debate and conduct can be mutually agreed upon and some basic principles recognised, provided these are not arbitrary, selective or quickly sacrificed to egos, personalised competitiveness or point-scoring. After that, let rigorous and robust debates and disagreements build within the boundaries of informed respect and through methods of inquiry that expand outward and include those we disagree with, rather than following narrow, parochial and self-contradictory paths.

(Image above: Painting by Saira Wasim, Please For Peace, 2008. Gouache, gold leaf, marbling and ink on wasli paper. 21.5 x 22.8 inches.)

[1] The descriptions of him ranged from elitist colonial apologist to, a racist and Islamophobic layman.

[2] The All Pakistan Private Schools Management Association and The All Pakistan Private Schools Federation (which included ‘English-medium’ schools, considered to be bastions of “liberal thinking”) banned Malala’s autobiography in all their affiliate schools and their libraries. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/inspiration-or-danger-private-schools-in-pakistan-ban-malala-yousafzais-book-8930925.html. Public events around her book were attacked and shut down.