Nadeem F. Paracha explains the historical evolution of Bazaar Politics in Pakistan and how it has influenced the government and Supreme Court during the ongoing COVID-19 lockdown debate.

It is a fallacy to think that the federal government and then the Supreme Court of Pakistan are looking to almost completely fold the lockdown policies of the provinces, especially Sindh, ‘for the sake of the poor.’ In fact, the SC has actually been quite clear on why it wants markets and malls to open: i.e. For the sake of big and small businesses.

But as the federal government continues to shield the same thinking with the entirely populist rhetoric of easing the lockdown to help the poor, some of its ministers did not hold back their glee after the SC announced its rather controversial decision to open the markets.

Nevertheless, the manner in which the SC supported the arguments of traders and businesses, some of whose representatives were present in the court, and also, the way members of the federal government and some TV anchors with stakes in malls and other enterprises rejoiced, it is now quite clear who really wants to get rid of the whole idea of lockdowns, even in the event of ever-increasing numbers of Covid-19 infections and deaths in the country.

Surprisingly, those who have criticised the federal government’s feeble attitude towards the pandemic and SC’s recent judgment, are yet to investigate something which has become rather obvious: i.e. it is the business classes that have been lobbying hard to get the lockdowns removed.

What’s more, the critical space created by the lobbyists has also been used to castigate the provincial government of Sindh because it was the first to initiate a lockdown and is still reluctant to completely ease it as desired by the federal government and as demanded by SC.

On 12 May this year, one of Thailand’s leading dailies, the Bangkok Post reported that “(in Thailand) the private sector is calling on the government to continue easing its lockdown measures to allow businesses, particularly those related to tourism and supply chains, to restart.” The newspaper then added that the sector wanted this to be done “to curb escalating unemployment.”

Indeed, unemployment is an issue. But at the moment, human lives should take precedence, especially during a pandemic triggered by a virus that is still a mystery and for which there is yet no known vaccine or cure.

And it is also a fact that governments in developing countries, especially those being headed by pro-business regimes, do not want to spend large sums of money to aid the poor or break away from a process in which private businesses, big or small, create jobs and capital to keep millions of poor folks economically engaged — even if the nature of this engagement largely remains hand-to-mouth for most.

The narrative against lockdowns is thus largely being constructed by the business classes and proliferated through their lobbyists in the media and the federal government. The unsaid bit in this narrative is that ‘we are making losses.’ The said bit is that rhetoric about how the poor are suffering. As if they weren’t before the Covid-19 outbreak.

Also, it will be the poor who are more likely to get infected by the virus now that the business lobby has succeeded in making the government and the courts to open things up. The dreadful idea of herd immunity is being dressed up as some noble pro-poor cause.

The politics of business

The foot-soldiers of the business lobby are small business folk and shop-owners. Ever since the late 1970s, organised traders have played a significant role in the politics of various Muslim countries, especially in Iran, Pakistan, Turkey and Egypt. This is often explained as ‘bazaar politics’ (or the politics of the marketplace).

The word ‘bazaar’ has Persian origins and means an enclosed marketplace. Twentieth-century Marxist analysis saw bazaar politics at the core of the political and economic action of the ‘petit-bourgeoisie’ even though many political scientists have also seen it as an extension of middle-class political activity.

The study of the bazaar in the context of politics is not that old, despite the fact that bazaars have been integral economic and physical mainstays of Muslim-majority regions for centuries. The expression ‘bazaar politics’ first emerged soon after the 1979 revolution in Iran. The traditional bazaars of the country played a noteworthy role in the turmoil which toppled the powerful Shah of Iran.

The action in this respect was initiated by trader and merchant groups operating inside Iran’s many bazaars. The revolutionary movement against the monarchy was driven by various forces which included the communists, secular democrats and the Islamic clergy. But it was the bazaars which eventually tilted the scale in favour of the clergy, and the revolution became ‘Islamic.’

The participation of groups formed inside Iran’s traditional marketplaces by traders, merchants and shop-owners in the revolution was influential enough for political scientists to begin studying the concept of bazaar politics. Many such studies discovered that some political activity in this context did take place prior to the 1979 revolution. But it was during and after the revolution that the bazaar emerged as a major political influencer.

M.E. Bonine and N.R. Keddie in 1981’s Modern Iran Dialectics demonstrate that the Shah’s ‘modernisation’ policies briefly benefitted the economy of the bazaars. However, this modernisation sought to shift economic activity away from traditional marketplaces or bazaars to modern souks and emporiums.

But this did not see the traditional marketplaces recede. Instead, with the continuing influx of migrants from rural and semi-rural areas to the cities, the traditional bazaars were ‘ruralised’. Their owners and consumers now overwhelmingly came from petit-bourgeoisie backgrounds and from transitional segments perched between traditional agrarian economics and modern urban capitalism.

Due to the disorienting impacts of haphazard modernisation, the customary bonds between the bazaars and the clergy strengthened. This aided the clergy during the revolutionary turmoil. No wonder then, Iran’s Islamic regime immediately inducted many members from bazaar organisations in the new regime.

Something similar happened in Pakistan. Riaz Hassan’s 1985 study “Religious, Political and Social Change in Pakistan” demonstrates that increasing and unplanned urbanisation between the late 1960s and the late 1970s left a large segment of the population leading a highly precarious existence which was subjected to all kinds of exploitation.

This generated a considerable amount of disillusionment with the modernist governments and their policies of economic and social development. The persistent insecurity of urban existence among many shopkeepers, traders and their families, over the years, resulted in the emergence of various religious movements.

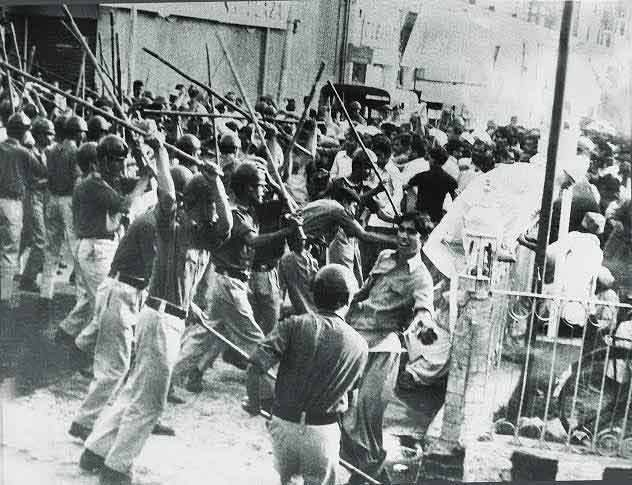

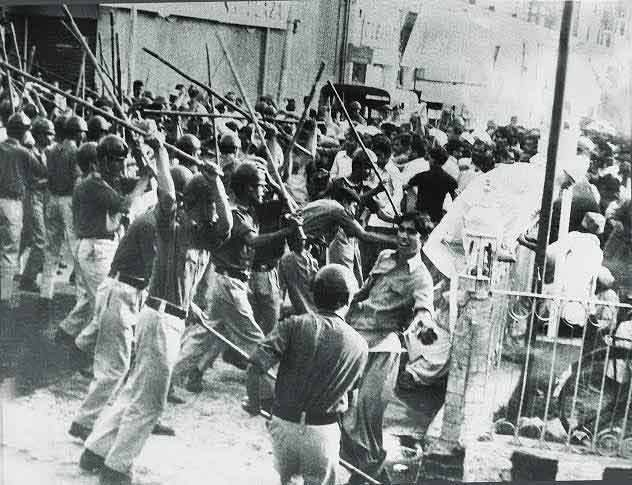

The number of mosques in the cities multiplied and, through them, religious influences further permeated social life. Much of this took place in the urban bazaar areas of Pakistan. The late political scientist Khalid B. Sayeed writes in The Nature and Direction of Change that the bazaar’s first major political endeavour in Pakistan was during the 1977 protest movement, against the populist Z.A. Bhutto regime. However, according to Phillip E. Jones, the bazaar was active during the 1968 anti-Ayub movement as well. But Sayeed is correct in pointing out that the trader outfits were not as radicalised in the 1960s as they became in the 1970s.

Sayeed writes that the traders had welcomed the Bhutto regime’s rhetoric against business groups fattened by the Ayub dictatorship, but quickly turned against him when he began to nationalise small and medium enterprises. As mentioned by Hassan, by the mid-1970s the bazaar had already established close links with the clergy and these links rapidly extended to the country’s religious parties.

Umair Javed, in his essay for the anthology New Perspectives on Pakistan’s Political Economy, writes that mosques were extensively used in bazaars to propel protests against the Bhutto regime.

Just as influential figures of bazaar politics were co-opted by Iran’s ‘Islamic’ regime, the conservative Gen Zia dictatorship in Pakistan appropriated various powerful trader outfits, many of whose members became part of the local, provincial and national assemblies.

From the 1980s onward, Pakistani bazaar politics has continued to operate through pressure groups that keep governments from imposing policies that are seen as unbeneficial to traders and shopkeepers. Trader organisations and alliances in the bazaars have also retained their exhibition of ‘piety’ and they often associate themselves with, and even spearhead, campaigns against certain religious minorities and against any move to reform the ‘Islamic’ entries in the constitution.

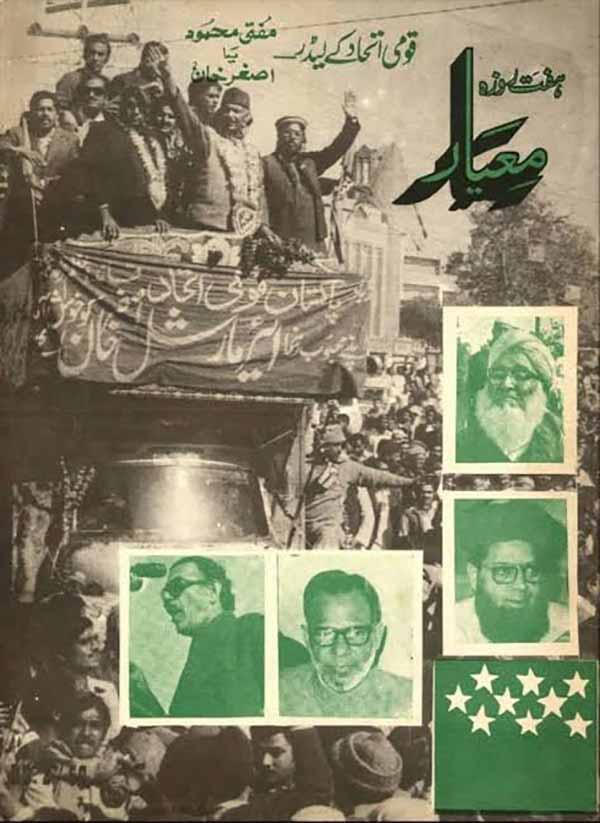

The PML-N inherited the bazaar as a constituency in the 1990s. But by the 2018 election, this constituency (in the Punjab) had split between PML-N, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf and Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan. There is no study, as such, on how the bazaar in Karachi evolved after it embraced the politics of the Jamaat-i-Islami and Jamiat-i-Ulema Pakistan in 1977.

Largely, the bazaar politics of Karachi has remained pragmatic. Because even though almost as conservative as the bazaar politics of Punjab, the one in Karachi hasn’t demonstrated as much support to causes that look to oust religious minorities, impose social morality or safeguard ‘Islamic laws,’ as much as Punjab’s bazaars have done in the last three decades.

Maybe the ethnic diversity of Karachi keeps this from happening, as the bazaars here are segmented between different ethnic groups. They are more concerned about safeguarding their respective groups’ economic stakes in a highly competitive, even contentious, ethno-political environment. That’s why, for example, one can expect campaigns to restrict the entry of certain minority communities in the bazaars of Punjab, but no such activity has ever been reported from the bazaars of Karachi.

Nevertheless, recently, there have been those in the current federal government and business group lobbyists in the media who have tried to upset the composure of the Sindh government by galvanising the traders and shop-keepers towards a narrative which states that the province’s government is ‘anti-Karachi’ and wants to usurp the resources of the city by undermining its economics through lockdowns.

It is a fallacy to think that the federal government and then the Supreme Court of Pakistan are looking to almost completely fold the lockdown policies of the provinces, especially Sindh, ‘for the sake of the poor.’ In fact, the SC has actually been quite clear on why it wants markets and malls to open: i.e. For the sake of big and small businesses.

But as the federal government continues to shield the same thinking with the entirely populist rhetoric of easing the lockdown to help the poor, some of its ministers did not hold back their glee after the SC announced its rather controversial decision to open the markets.

Nevertheless, the manner in which the SC supported the arguments of traders and businesses, some of whose representatives were present in the court, and also, the way members of the federal government and some TV anchors with stakes in malls and other enterprises rejoiced, it is now quite clear who really wants to get rid of the whole idea of lockdowns, even in the event of ever-increasing numbers of Covid-19 infections and deaths in the country.

Surprisingly, those who have criticised the federal government’s feeble attitude towards the pandemic and SC’s recent judgment, are yet to investigate something which has become rather obvious: i.e. it is the business classes that have been lobbying hard to get the lockdowns removed.

What’s more, the critical space created by the lobbyists has also been used to castigate the provincial government of Sindh because it was the first to initiate a lockdown and is still reluctant to completely ease it as desired by the federal government and as demanded by SC.

On 12 May this year, one of Thailand’s leading dailies, the Bangkok Post reported that “(in Thailand) the private sector is calling on the government to continue easing its lockdown measures to allow businesses, particularly those related to tourism and supply chains, to restart.” The newspaper then added that the sector wanted this to be done “to curb escalating unemployment.”

Indeed, unemployment is an issue. But at the moment, human lives should take precedence, especially during a pandemic triggered by a virus that is still a mystery and for which there is yet no known vaccine or cure.

And it is also a fact that governments in developing countries, especially those being headed by pro-business regimes, do not want to spend large sums of money to aid the poor or break away from a process in which private businesses, big or small, create jobs and capital to keep millions of poor folks economically engaged — even if the nature of this engagement largely remains hand-to-mouth for most.

The narrative against lockdowns is thus largely being constructed by the business classes and proliferated through their lobbyists in the media and the federal government. The unsaid bit in this narrative is that ‘we are making losses.’ The said bit is that rhetoric about how the poor are suffering. As if they weren’t before the Covid-19 outbreak.

Also, it will be the poor who are more likely to get infected by the virus now that the business lobby has succeeded in making the government and the courts to open things up. The dreadful idea of herd immunity is being dressed up as some noble pro-poor cause.

The politics of business

The foot-soldiers of the business lobby are small business folk and shop-owners. Ever since the late 1970s, organised traders have played a significant role in the politics of various Muslim countries, especially in Iran, Pakistan, Turkey and Egypt. This is often explained as ‘bazaar politics’ (or the politics of the marketplace).

The word ‘bazaar’ has Persian origins and means an enclosed marketplace. Twentieth-century Marxist analysis saw bazaar politics at the core of the political and economic action of the ‘petit-bourgeoisie’ even though many political scientists have also seen it as an extension of middle-class political activity.

The study of the bazaar in the context of politics is not that old, despite the fact that bazaars have been integral economic and physical mainstays of Muslim-majority regions for centuries. The expression ‘bazaar politics’ first emerged soon after the 1979 revolution in Iran. The traditional bazaars of the country played a noteworthy role in the turmoil which toppled the powerful Shah of Iran.

The action in this respect was initiated by trader and merchant groups operating inside Iran’s many bazaars. The revolutionary movement against the monarchy was driven by various forces which included the communists, secular democrats and the Islamic clergy. But it was the bazaars which eventually tilted the scale in favour of the clergy, and the revolution became ‘Islamic.’

The participation of groups formed inside Iran’s traditional marketplaces by traders, merchants and shop-owners in the revolution was influential enough for political scientists to begin studying the concept of bazaar politics. Many such studies discovered that some political activity in this context did take place prior to the 1979 revolution. But it was during and after the revolution that the bazaar emerged as a major political influencer.

M.E. Bonine and N.R. Keddie in 1981’s Modern Iran Dialectics demonstrate that the Shah’s ‘modernisation’ policies briefly benefitted the economy of the bazaars. However, this modernisation sought to shift economic activity away from traditional marketplaces or bazaars to modern souks and emporiums.

But this did not see the traditional marketplaces recede. Instead, with the continuing influx of migrants from rural and semi-rural areas to the cities, the traditional bazaars were ‘ruralised’. Their owners and consumers now overwhelmingly came from petit-bourgeoisie backgrounds and from transitional segments perched between traditional agrarian economics and modern urban capitalism.

Due to the disorienting impacts of haphazard modernisation, the customary bonds between the bazaars and the clergy strengthened. This aided the clergy during the revolutionary turmoil. No wonder then, Iran’s Islamic regime immediately inducted many members from bazaar organisations in the new regime.

Something similar happened in Pakistan. Riaz Hassan’s 1985 study “Religious, Political and Social Change in Pakistan” demonstrates that increasing and unplanned urbanisation between the late 1960s and the late 1970s left a large segment of the population leading a highly precarious existence which was subjected to all kinds of exploitation.

This generated a considerable amount of disillusionment with the modernist governments and their policies of economic and social development. The persistent insecurity of urban existence among many shopkeepers, traders and their families, over the years, resulted in the emergence of various religious movements.

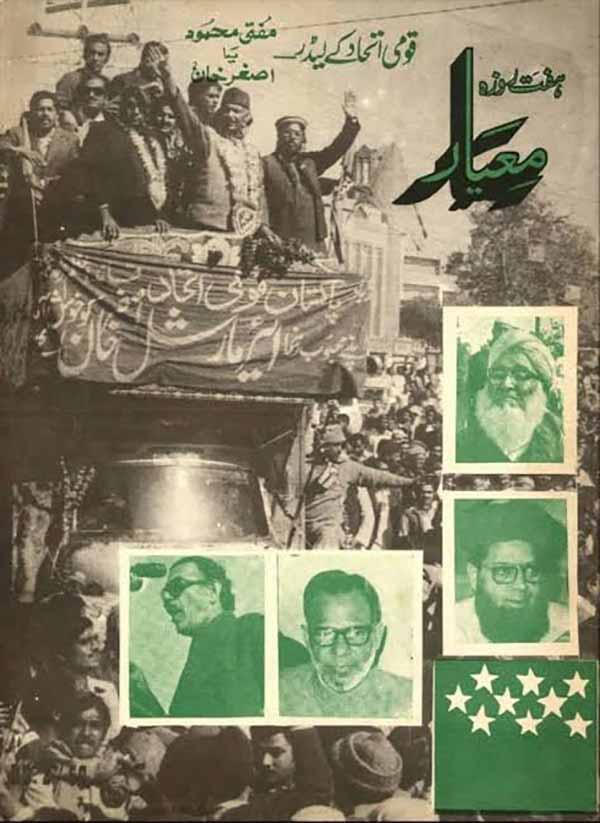

The number of mosques in the cities multiplied and, through them, religious influences further permeated social life. Much of this took place in the urban bazaar areas of Pakistan. The late political scientist Khalid B. Sayeed writes in The Nature and Direction of Change that the bazaar’s first major political endeavour in Pakistan was during the 1977 protest movement, against the populist Z.A. Bhutto regime. However, according to Phillip E. Jones, the bazaar was active during the 1968 anti-Ayub movement as well. But Sayeed is correct in pointing out that the trader outfits were not as radicalised in the 1960s as they became in the 1970s.

Sayeed writes that the traders had welcomed the Bhutto regime’s rhetoric against business groups fattened by the Ayub dictatorship, but quickly turned against him when he began to nationalise small and medium enterprises. As mentioned by Hassan, by the mid-1970s the bazaar had already established close links with the clergy and these links rapidly extended to the country’s religious parties.

Umair Javed, in his essay for the anthology New Perspectives on Pakistan’s Political Economy, writes that mosques were extensively used in bazaars to propel protests against the Bhutto regime.

Just as influential figures of bazaar politics were co-opted by Iran’s ‘Islamic’ regime, the conservative Gen Zia dictatorship in Pakistan appropriated various powerful trader outfits, many of whose members became part of the local, provincial and national assemblies.

From the 1980s onward, Pakistani bazaar politics has continued to operate through pressure groups that keep governments from imposing policies that are seen as unbeneficial to traders and shopkeepers. Trader organisations and alliances in the bazaars have also retained their exhibition of ‘piety’ and they often associate themselves with, and even spearhead, campaigns against certain religious minorities and against any move to reform the ‘Islamic’ entries in the constitution.

The PML-N inherited the bazaar as a constituency in the 1990s. But by the 2018 election, this constituency (in the Punjab) had split between PML-N, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf and Khadim Hussain Rizvi’s Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan. There is no study, as such, on how the bazaar in Karachi evolved after it embraced the politics of the Jamaat-i-Islami and Jamiat-i-Ulema Pakistan in 1977.

Largely, the bazaar politics of Karachi has remained pragmatic. Because even though almost as conservative as the bazaar politics of Punjab, the one in Karachi hasn’t demonstrated as much support to causes that look to oust religious minorities, impose social morality or safeguard ‘Islamic laws,’ as much as Punjab’s bazaars have done in the last three decades.

Maybe the ethnic diversity of Karachi keeps this from happening, as the bazaars here are segmented between different ethnic groups. They are more concerned about safeguarding their respective groups’ economic stakes in a highly competitive, even contentious, ethno-political environment. That’s why, for example, one can expect campaigns to restrict the entry of certain minority communities in the bazaars of Punjab, but no such activity has ever been reported from the bazaars of Karachi.

Nevertheless, recently, there have been those in the current federal government and business group lobbyists in the media who have tried to upset the composure of the Sindh government by galvanising the traders and shop-keepers towards a narrative which states that the province’s government is ‘anti-Karachi’ and wants to usurp the resources of the city by undermining its economics through lockdowns.