The world will never be the same again—the social relations, political configurations, economic relations and the very process of globalization might undergo a change. It will transform the world beyond recognition. The 20th century and the first two decades of the 21st century saw radical changes in all the above-mentioned fields. We started the 20th century with brutal wars between world powers followed by process of integration between two opposing political camps, which, in turn, was followed by a process of unfettered globalization. This was a process which witnessed social, political and economic integration of societies situated thousands of miles apart on the world map. Political philosophies and religious movements rose and were obliterated from the face of these societies, as change remained the only constant in world affairs. Economic ideas became gospel truths and were washed away by tidal waves of socioeconomic forces. Only those societies rose in prominence and strength which adjusted to the nature of changes in the physical environment and adapted to social, political and economic forces around them. A society may continue to live in an environment totally ignoring forces of change, but then it will have to face the consequences of becoming irrelevant or, even worse, the obliteration of its political and social structures, giving rise to new ones. As US General Eric Shinseki said, “If you don’t like change, you're going to dislike irrelevance even more.”

The religious clergy of Pakistan is one element in this society which is simply ignoring all the changes taking place in the world and society around them. And they want society itself to ignore these changes and stagnate along with them. A very dynamic and vibrant religious tradition of Islam, in their hands, has been turned into some static principles and a ritualized lifestyle. For them religion is an interpretation contained in the books from colonial era—fossilized, static, unchanging and unresponsive to the changing circumstances. And this has been happening since independence and undoubtedly we faced disaster after disaster because of this fossilized mindset.

This time it is different: life is changing beyond recognition and the circumstances demand that we adjust to these changes or face disaster for our social and political structures.

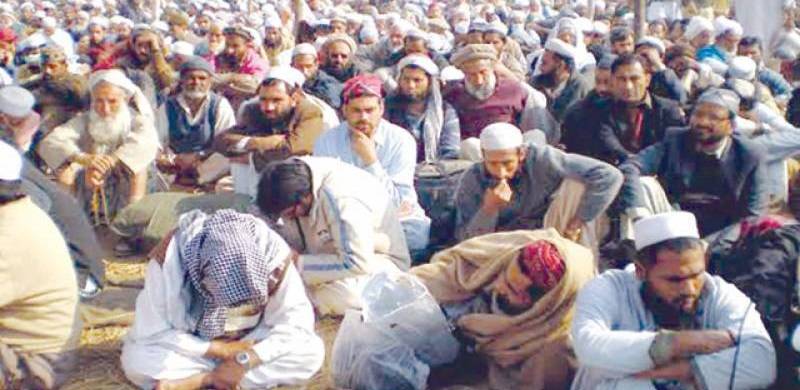

Experts know that Pakistan could not have escaped the spread of COVID-19 because of its proximity to China and Iran—the two countries where large segments of populations suffered from the pandemic. Moreover, there is the cosmopolitan nature of Pakistan’s social, political and economic elite to consider. But even if this were true, allowing the Tablighi Ijtama to take place in Punjab was a big mistake as it was just like incubating the virus and then sending out carriers all over the country to further spread the disease. The failure of the state machinery to convince the religious clergy from stopping Jummah Prayers in their mosques is another example of religious clergy unresponsive to changes taking place around them.

Most religious groups or trends in our society think that responding to worldly changes means defeating the principles, rules and spirit of religion. This interpretation of religion, unresponsive to worldly changes, emanates from reformist movements that originated in British India. Religious reformist movements took birth in British India at a time when the colonialists were assuming political and military control of Indian society. All these movements were, one way or the other, inspired by religious scholars who faced the problem of the demise of Muslim political and military power in India. They had long grappled with the question of how to organize the Muslim community in the absence of an overarching power such as the Mughal Empire.

These reformist movements interpreted religion in the colonial context, where Muslims didn’t enjoy political and military control of society and, therefore, were alienated from the British colonial government. 19th-century reformist movements like the one based at Deoband and the second led by Maulana Ahmed Raza Barelvi (popularly known as the Barelvi movement) didn’t pose any military or political threat to the colonial government. But they were nevertheless alienated from the British—as their leaders kept a distance from the colonial government and presented an interpretation of Quran, Sunnah and Islamic history that was quasi-confrontational. In sum their interpretation didn’t preach loyalty to the British government.

The Jamat-e-Islami’s ideological-foundational text was written during the colonial period and it just as full of stories about the glorious past of Islamic history: an attitude which prevented its adherents from observing loyalty to the British colonial government. This much is understandable.

Now fast-forward to today’s situation: social media is full of fiery speeches of Pakistani clergy that revolve around the theme that this state and its machinery was bent upon shutting down the mosques in fear of COVID-19. Their rhetoric indicates that these mullahs are now treating the Pakistani state and its machinery with the mindset that was developed during the colonial period— i.e. to oppose every move of the government considered alien by the clergy. Ironically during the British period these reformist movements never gathered the courage to fully oppose the colonial government, as it was harsh and brutal. The Pakistani government, on the other hand, appears to be easy prey; always reluctant to use force against the clergy, especially in urban areas.

The demise of the Mughal state in India created a situation for the Muslim clergy where they lost self-confidence. It forced them to run away from every kind of innovative thinking or developing a response to the changing political and social environment in Colonial India. This led to a fossilized, static and unresponsive attitude to social, political and environmental change – eventually leading to the situation that we now find ourselves in.

The ability to develop a response to changing circumstances was never present in this clergy or their predecessors. But they were politically docile once - a quality which should have been present in today's clergy and ought not to have been valued in their colonial predecessors. The very opposite proved true! This ought to be cause for reflection for our political, military and intellectual elites.

If I were to answer the question of why these clerics are so much more aggressive and destructive in our post-colonial era, it would be this: a policy of appeasement towards the clergy has been a norm in our society since the 1970s.

Currently we are living under a political setup headed by Imran Khan, a person who used a “religion card” and clergy to destabilize the previous political government of Nawaz Sharif. Now he fears that the same card and clergy could be used against his own government. Aside from this, we have in our system officials who have been accused of belonging to heterodox sects in the past. They still feel vulnerable against this aggressive and destructive side of the clergy. Hence we see decisions coming from the government not to block the holding of religious assemblies, such as the one in Lahore.

This is not a time to secure one's seats in the power structure. Instead, this is a time for innovative thinking and developing a response to changing circumstances – or else facing irrelevance, perhaps even a disaster.