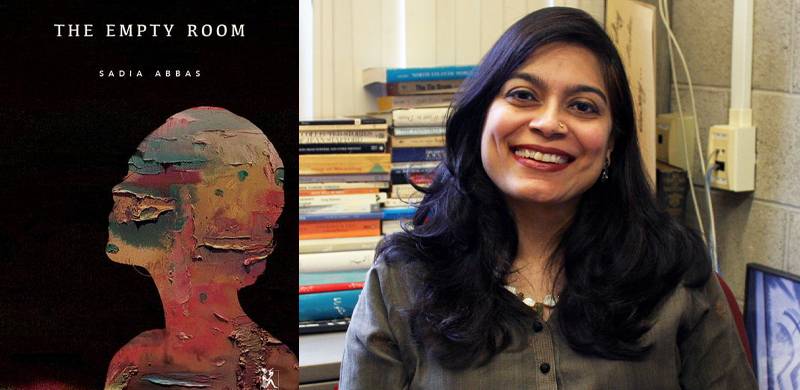

The book, as an object, sits in front of me, tangible and solid. Though the world it has scar-opened inside of me, is intangible and amorphous. There is still the gun-shot wound piercing through me, the hollow arc of creativity’s spark racing through it all. ‘The Empty Room’, by Sadia Abbas, is a story of how a house-wife reconciles with her ability to paint, while inhabiting the house of horrors. This house is both literal and metaphoric. It is the story of Tahira’s journey into her own, into her power.

Before I started reading ‘The Empty Room’, I had the good luck of attending Sadia Abbas’ talk on the same at KLF earlier this month. As we were listening to her tell us about the ‘utopia’ and magic of gardens, I remember in my own internal world being plagued by the thought that perhaps gardens represented the unconscious and in turn, I sought to understand silence in them in terms of being ‘unconscious.

When I placed this question to Sadia, she had enigmatically replied that the garden is not representative of the unconscious per se in her book, but rather “a symptom of the desire for the unconscious.” After having read the book, I feel this desire manifests in the lives of the characters of ‘The Empty Room’ as seeking the deeper self (perhaps the unconscious) whether that be in the form of love, revolution or creativity.

Returning to the central issue of the lead character, I feel the character arc of the protagonist, Tahira, is swiftly and profoundly significant – it reaches utter lows of shame, helplessness and lack and then reaching seaward, finally enhances into an imitation of swimming, till the final uplift. The imitation of swimming is built upon habit – and there is a wonderful section in the book where Tahira maintains a ritualistic routine, which helps her out of her darkest days. It makes me think of the enormous impact of habit.

Tahira, as a creative artist, is submerged into the rigmarole life of an arranged marriage. It is remarks by her mother-in-law and sisters-in-law that add insult to injury: “Pay attention, how will you learn if you sit there like a lost princess?” The adjective ‘lost’ is very telling, of the creative individual’s certain abstractedness and lack of conformity. So then, how will Tahira come to terms with a conventional set-up, when her main calling is to paint?

As she slowly descents into her marriage with a ‘taciturn’ and rude Shehzad, she finds even her thoughts affected, not just her words. Take this quote for example: “Tahira thought savagely, when she was able to think savagely, in those days, which was not often.” So she is under a spell of conformity and conventional discipline, where her inner life has been stifled. The ailment has reached the deeper ‘subconscious’ of thoughts and imagination. This is, of course, terrible for her expression as a painter. Her role is a diminished one, as she turns a ‘slow, oxygenless blue’ cornered at family gatherings. She is not allowed to express, to be herself, and at what cost?

I think the fixity of the pettiness of her in-laws, contrasts with her ability of imagination which is unbound. Another stark contrast present in the novel is in the form of Andaleep, Tahira’s best friend from school days. Andaleep has an ‘anarchic laughter’ and is fiercely independent and even in genuine love with two men at the same time. These contrasts reveal to us the intensity of Tahira’s predicament of a life of conventional doom when something of her spirit is unfettered and defiant, like her imagination, like her best friend. For does not having a best friend who defies the norm, certainly betray Tahira’s own propensity to some sort of similar expression? This does come out finally in her paintings.

The series ‘The Empty Room’ which she takes to painting beyond mid-way in the novel works to create space inside the painting, inside her now acquired studio and inside Tahira’s mind. I was particularly drawn to the ability of creativity which can be subtly subversive. Derrida would place the ‘trace’ somewhere here on this ability and show how meanings are forever altered and ‘deferred’ from here on in the text. Tahira is starting to find her own voice in the silent form of painting.

Tahira’s sensitivity is reflected in lines such as: “I think silence has colours” and “Are love and resentment to be forever mingled?” The first defiant painting she makes after her marriage is that of her own son and presents it as a gift to her uninterested mother-in-law. The painting of her grandson is a gift which cannot be refused for it would seem improper! How the tables have turned! Also, the painting would be hung inside the mother-in-law’s room which would be a constant reminder and intrusion of her physical space. As Tahira’s physical and mental space was intruded, now a single painting would do the same for her mother-in-law and in this regard, I see this gift as an act of revenge.

Tahira, unlike Andaleep, is a person of silences and acquiescence. She tells Andaleep in one of their heart-to-hearts: “Besides, we were all brought up not to speak about these things.” The validity of propriety is questioned in this novel. When is it okay, after all, to speak openly about such things as married, familial life?

For a good part of the book, I felt I was observing the act of chiseling a semi-precious stone. I was waiting for the work to finish. Structurally, at one point, the language of the novel moves from its ordinary register into that of a prose-poem. The move is eloquent. It comes about in the form of a love-letter addressed to Andaleep. We also, at a point, move from reality to dream – when Tahira’s subconscious is betraying her towards an alternate, fluid, dreamy reality. These moves in style have an overpowering affect as they come after a long hiatus. This is symbolic also, of Tahira’s journey towards realisation and expression which come after a long delay.

As readers, we wait for Tahira to paint again, to dream again, and to be assertive in some manner. So these structural nuances blend in with her final demand – to move out, to have a studio of her own, and to not be disturbed as far as her art goes. The novel seems to suggest that that is the real conquest – for she is still in her duplicitous marriage at the end. However, this seems to be a minor error now, as her growth as a character has been to rework the given realities she found herself in post-marriage.

Returning to the mention of gardens, I think what they mean to me has altered, in some irreversible manner. In the prose-poem there are these evocative lines: “The garden must be orderly yet tempt with the imminence of disorder, seem on the beautiful verge of explosion.” Tahira’s own studio in her own place is finally symbolic of such a place. The order and decorum of it is spatial and physical and yet, with every painting, there is the “Imminence of disorder…the beautiful verge of explosion.” As each of her art work finally carries all that desire, loss and melancholy had painted into her being.

There are several other facets to this novel, like that of discovering motherhood under trying circumstances, death, politics and unfaithfulness. However, Tahira’s journey and silenced form has left me with the finest lament of all.

Before I started reading ‘The Empty Room’, I had the good luck of attending Sadia Abbas’ talk on the same at KLF earlier this month. As we were listening to her tell us about the ‘utopia’ and magic of gardens, I remember in my own internal world being plagued by the thought that perhaps gardens represented the unconscious and in turn, I sought to understand silence in them in terms of being ‘unconscious.

When I placed this question to Sadia, she had enigmatically replied that the garden is not representative of the unconscious per se in her book, but rather “a symptom of the desire for the unconscious.” After having read the book, I feel this desire manifests in the lives of the characters of ‘The Empty Room’ as seeking the deeper self (perhaps the unconscious) whether that be in the form of love, revolution or creativity.

Returning to the central issue of the lead character, I feel the character arc of the protagonist, Tahira, is swiftly and profoundly significant – it reaches utter lows of shame, helplessness and lack and then reaching seaward, finally enhances into an imitation of swimming, till the final uplift. The imitation of swimming is built upon habit – and there is a wonderful section in the book where Tahira maintains a ritualistic routine, which helps her out of her darkest days. It makes me think of the enormous impact of habit.

Tahira, as a creative artist, is submerged into the rigmarole life of an arranged marriage. It is remarks by her mother-in-law and sisters-in-law that add insult to injury: “Pay attention, how will you learn if you sit there like a lost princess?” The adjective ‘lost’ is very telling, of the creative individual’s certain abstractedness and lack of conformity. So then, how will Tahira come to terms with a conventional set-up, when her main calling is to paint?

As she slowly descents into her marriage with a ‘taciturn’ and rude Shehzad, she finds even her thoughts affected, not just her words. Take this quote for example: “Tahira thought savagely, when she was able to think savagely, in those days, which was not often.” So she is under a spell of conformity and conventional discipline, where her inner life has been stifled. The ailment has reached the deeper ‘subconscious’ of thoughts and imagination. This is, of course, terrible for her expression as a painter. Her role is a diminished one, as she turns a ‘slow, oxygenless blue’ cornered at family gatherings. She is not allowed to express, to be herself, and at what cost?

I think the fixity of the pettiness of her in-laws, contrasts with her ability of imagination which is unbound. Another stark contrast present in the novel is in the form of Andaleep, Tahira’s best friend from school days. Andaleep has an ‘anarchic laughter’ and is fiercely independent and even in genuine love with two men at the same time. These contrasts reveal to us the intensity of Tahira’s predicament of a life of conventional doom when something of her spirit is unfettered and defiant, like her imagination, like her best friend. For does not having a best friend who defies the norm, certainly betray Tahira’s own propensity to some sort of similar expression? This does come out finally in her paintings.

The series ‘The Empty Room’ which she takes to painting beyond mid-way in the novel works to create space inside the painting, inside her now acquired studio and inside Tahira’s mind. I was particularly drawn to the ability of creativity which can be subtly subversive. Derrida would place the ‘trace’ somewhere here on this ability and show how meanings are forever altered and ‘deferred’ from here on in the text. Tahira is starting to find her own voice in the silent form of painting.

Tahira’s sensitivity is reflected in lines such as: “I think silence has colours” and “Are love and resentment to be forever mingled?” The first defiant painting she makes after her marriage is that of her own son and presents it as a gift to her uninterested mother-in-law. The painting of her grandson is a gift which cannot be refused for it would seem improper! How the tables have turned! Also, the painting would be hung inside the mother-in-law’s room which would be a constant reminder and intrusion of her physical space. As Tahira’s physical and mental space was intruded, now a single painting would do the same for her mother-in-law and in this regard, I see this gift as an act of revenge.

Tahira, unlike Andaleep, is a person of silences and acquiescence. She tells Andaleep in one of their heart-to-hearts: “Besides, we were all brought up not to speak about these things.” The validity of propriety is questioned in this novel. When is it okay, after all, to speak openly about such things as married, familial life?

For a good part of the book, I felt I was observing the act of chiseling a semi-precious stone. I was waiting for the work to finish. Structurally, at one point, the language of the novel moves from its ordinary register into that of a prose-poem. The move is eloquent. It comes about in the form of a love-letter addressed to Andaleep. We also, at a point, move from reality to dream – when Tahira’s subconscious is betraying her towards an alternate, fluid, dreamy reality. These moves in style have an overpowering affect as they come after a long hiatus. This is symbolic also, of Tahira’s journey towards realisation and expression which come after a long delay.

As readers, we wait for Tahira to paint again, to dream again, and to be assertive in some manner. So these structural nuances blend in with her final demand – to move out, to have a studio of her own, and to not be disturbed as far as her art goes. The novel seems to suggest that that is the real conquest – for she is still in her duplicitous marriage at the end. However, this seems to be a minor error now, as her growth as a character has been to rework the given realities she found herself in post-marriage.

Returning to the mention of gardens, I think what they mean to me has altered, in some irreversible manner. In the prose-poem there are these evocative lines: “The garden must be orderly yet tempt with the imminence of disorder, seem on the beautiful verge of explosion.” Tahira’s own studio in her own place is finally symbolic of such a place. The order and decorum of it is spatial and physical and yet, with every painting, there is the “Imminence of disorder…the beautiful verge of explosion.” As each of her art work finally carries all that desire, loss and melancholy had painted into her being.

There are several other facets to this novel, like that of discovering motherhood under trying circumstances, death, politics and unfaithfulness. However, Tahira’s journey and silenced form has left me with the finest lament of all.