Even though the memory is sort of distant, I distinctly recall reading a quote by Orhan Pamuk which remarked that it takes two years for one to recover from a heartbreak. This recollection is intertwined with the same refrain which a professor once said: “death and divorce mark you, they take time to wear off.” So what is in fact this intangible predicament that one cannot seem to shake off?

Love is one of the most cliché and universal of topics, and yet the same word can signify singularity, depth and solace. It is a cluster word which attracts to itself a host of other phenomena – this varies from instinctive predicaments like jealousy and possessiveness to social constructs such as marriage. Love may be a pulse of mutual affection or sting with that bittersweet tendency of unrequitedness.

It is one of the strongest themes of literature, and as we read of it, we live and die a little ourselves in the experience of visiting it. Though even close readings are rather from the vantage position of detachment. It is like a screen (of imagination) on which we see dynamic emotions but they are not our own. Yet, this magical mental theatre can turn metaphoric in seconds, and come very close to us as the hiss of a snake – it can sting into our own psyche. We are all familiar with this mirroring tendency of literature when it starts to follow us home.

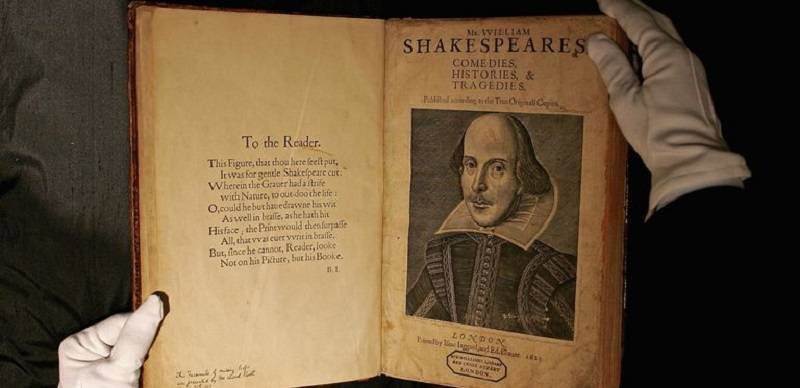

I started to think of this eternal and lingering topic tonight as I was leafing through Shakespeare’s sonnets: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds/ Admit impediments. Love is not love/ Which alters when it alteration finds.” It is interesting that this famous ‘wedding ceremony’ sonnet does not refer to a paper commitment, but rather to an affinity of the minds. This old-school tendency that love is eternal and constant, that it is not fickle is questioned by the modern mind, and yet remains desirous as well. The phrase “love is not love” is a statement one would like to purchase on Valentine’s Day. Simply because it is one of those days when there is too much cliché in the air. Akin to a butcher’s knife, this phrase brings with it a certain marked silence. “Love is not love” – and even taken out of context, and lain for a semantics analysis, there would exist a negation which cleanses the word of its own faulty exaggerations. If we consider the following line: “Which alters when it alteration finds,” it is again very old-worldly to those professing falsely grand notions of concepts such as polyamory. Though it seems to be the thing of shadows and persistence, yet it does not seem to be intrinsically inconstant.

In lines 11-12 of the famous sonnet 130, Shakespeare writes: “I grant I never saw a goddess go;/ My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.” These lines affirm that he has not witnessed a goddess (here, in a sense it would include an angel, or a mythic creature) and thus renounces the other-worldly longing. He states that what we have and should treasure is truly here. His mistress does not have eyes ‘like the sun’ but rather is an ordinary, earthly woman, so much the more real. These lines echo in Wallace Steven’s assertion in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird:

“O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?”

I think a very important idea is laid out here and it is contradictory in nature. For is not love a thing of intense subjectivity? And in that subjectivity do we not seek the ideal, the perfect, the other-worldly? And yet that strains toward the unattainable. In one of its forms, which is unrequited love, perhaps it becomes stronger and pulsates with a higher consciousness. Petrarch (14th Century Italian poet) saw a certain Laura for the first time in a church in Avignon, as the light was falling on her in certain angles; he fell in love at first sight. He could never unite with Laura, though he wrote 366 poems dedicated to her over a period of several years. A glimpse of his writings is as follows:

“O limpid stream,

That mirrorest her sweet face, her eyes so clear,

And of their living light canst catch the beam!

I envy thee her presence pure and dear.”

What we can never have, as in Petrarch’s case, creates its own form of intense longing and this is present not just in Petrarch’s sonnets but in countless instances of melancholic literature. A couple of such stories that come to mind are Tonio Kruger by Thomas Mann and Gertrude by Herman Hesse. These stories carry in themselves the sense of the sea which is ever present but is also constantly moving further and further away. However, the irony of such a situation is often beset by turbulent and negative emotion. To stay with Hesse here, he writes in Gertrude: “If that was love, with cruelty here and humiliation there, then it was better to live without love.”

It would be better to live without love, and yet the alarming inevitably of being perpetually in the snares of it is also present in the novel. This “sea of troubles” is yet I feel a truer depiction of whatever it is that love is made of than an easy-come-easy-go modernity. I think perhaps flings, temporary affairs, ‘friends with benefits’ and all sorts of other phenomena should not be a part of the discourse of love. For if it alters, when it alteration finds, is it love indeed? If it does not leave some sort of lasting, at times even devastating impact, is it really love?

We look to literature to find answers, to make connections, to engage in a creative and even at times life changing activity, not just to pass the time. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in a sometimes overlooked poem he ascribes to Ophelia, states:

“Doubt thou the stars are fire,

Doubt that the sun doth move,

Doubt truth to be a liar,

But never doubt I love.”

I say, ‘overlooked’ because perhaps in his subsequent cruelty we do not reflect on this cryptic gesture. These are simple lines, not part and parcel of Hamlet’s dense soliloquies or his ambivalent or caustic remarks. Defying all complexity, love then, is simple it seems. Yet, it is not surface simple nor casual. It seems to hit you with a force, able to change your very constitution.

Simple though it may be, once it goes through your soul as “wine through water” like in the case of Catherine of Wuthering Heights, it continues to retain its mystery. I’ll end with these following lines by Neruda, which seem to me to tell a story of unrequited love:

“Is there anything in the world sadder

than a train standing in the rain?”

The train is symbolically and terribly constant, and the rain is continuous. There is nothing else in the world that could be more moving (than love.)

Love is one of the most cliché and universal of topics, and yet the same word can signify singularity, depth and solace. It is a cluster word which attracts to itself a host of other phenomena – this varies from instinctive predicaments like jealousy and possessiveness to social constructs such as marriage. Love may be a pulse of mutual affection or sting with that bittersweet tendency of unrequitedness.

It is one of the strongest themes of literature, and as we read of it, we live and die a little ourselves in the experience of visiting it. Though even close readings are rather from the vantage position of detachment. It is like a screen (of imagination) on which we see dynamic emotions but they are not our own. Yet, this magical mental theatre can turn metaphoric in seconds, and come very close to us as the hiss of a snake – it can sting into our own psyche. We are all familiar with this mirroring tendency of literature when it starts to follow us home.

I started to think of this eternal and lingering topic tonight as I was leafing through Shakespeare’s sonnets: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds/ Admit impediments. Love is not love/ Which alters when it alteration finds.” It is interesting that this famous ‘wedding ceremony’ sonnet does not refer to a paper commitment, but rather to an affinity of the minds. This old-school tendency that love is eternal and constant, that it is not fickle is questioned by the modern mind, and yet remains desirous as well. The phrase “love is not love” is a statement one would like to purchase on Valentine’s Day. Simply because it is one of those days when there is too much cliché in the air. Akin to a butcher’s knife, this phrase brings with it a certain marked silence. “Love is not love” – and even taken out of context, and lain for a semantics analysis, there would exist a negation which cleanses the word of its own faulty exaggerations. If we consider the following line: “Which alters when it alteration finds,” it is again very old-worldly to those professing falsely grand notions of concepts such as polyamory. Though it seems to be the thing of shadows and persistence, yet it does not seem to be intrinsically inconstant.

In lines 11-12 of the famous sonnet 130, Shakespeare writes: “I grant I never saw a goddess go;/ My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.” These lines affirm that he has not witnessed a goddess (here, in a sense it would include an angel, or a mythic creature) and thus renounces the other-worldly longing. He states that what we have and should treasure is truly here. His mistress does not have eyes ‘like the sun’ but rather is an ordinary, earthly woman, so much the more real. These lines echo in Wallace Steven’s assertion in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird:

“O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?”

I think a very important idea is laid out here and it is contradictory in nature. For is not love a thing of intense subjectivity? And in that subjectivity do we not seek the ideal, the perfect, the other-worldly? And yet that strains toward the unattainable. In one of its forms, which is unrequited love, perhaps it becomes stronger and pulsates with a higher consciousness. Petrarch (14th Century Italian poet) saw a certain Laura for the first time in a church in Avignon, as the light was falling on her in certain angles; he fell in love at first sight. He could never unite with Laura, though he wrote 366 poems dedicated to her over a period of several years. A glimpse of his writings is as follows:

“O limpid stream,

That mirrorest her sweet face, her eyes so clear,

And of their living light canst catch the beam!

I envy thee her presence pure and dear.”

What we can never have, as in Petrarch’s case, creates its own form of intense longing and this is present not just in Petrarch’s sonnets but in countless instances of melancholic literature. A couple of such stories that come to mind are Tonio Kruger by Thomas Mann and Gertrude by Herman Hesse. These stories carry in themselves the sense of the sea which is ever present but is also constantly moving further and further away. However, the irony of such a situation is often beset by turbulent and negative emotion. To stay with Hesse here, he writes in Gertrude: “If that was love, with cruelty here and humiliation there, then it was better to live without love.”

It would be better to live without love, and yet the alarming inevitably of being perpetually in the snares of it is also present in the novel. This “sea of troubles” is yet I feel a truer depiction of whatever it is that love is made of than an easy-come-easy-go modernity. I think perhaps flings, temporary affairs, ‘friends with benefits’ and all sorts of other phenomena should not be a part of the discourse of love. For if it alters, when it alteration finds, is it love indeed? If it does not leave some sort of lasting, at times even devastating impact, is it really love?

We look to literature to find answers, to make connections, to engage in a creative and even at times life changing activity, not just to pass the time. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in a sometimes overlooked poem he ascribes to Ophelia, states:

“Doubt thou the stars are fire,

Doubt that the sun doth move,

Doubt truth to be a liar,

But never doubt I love.”

I say, ‘overlooked’ because perhaps in his subsequent cruelty we do not reflect on this cryptic gesture. These are simple lines, not part and parcel of Hamlet’s dense soliloquies or his ambivalent or caustic remarks. Defying all complexity, love then, is simple it seems. Yet, it is not surface simple nor casual. It seems to hit you with a force, able to change your very constitution.

Simple though it may be, once it goes through your soul as “wine through water” like in the case of Catherine of Wuthering Heights, it continues to retain its mystery. I’ll end with these following lines by Neruda, which seem to me to tell a story of unrequited love:

“Is there anything in the world sadder

than a train standing in the rain?”

The train is symbolically and terribly constant, and the rain is continuous. There is nothing else in the world that could be more moving (than love.)