Once the leader of Russian Revolution, Valadimir Lenin told the members of communist student organisation that they should not worry when they were unable to comprehend a philosophical text after first reading, “You should read it twice and then thrice and repeatedly and it will start to speak to you in this way” Lenin is said to have told the young communists. I read this lecture of Lenin sometimes during my university days and made it a habit to read difficult texts repeatedly before they started to speak to me.

Does this make me a Marxist-Leninist? No, it doesn’t. I am not a Marxist pure and simple. As they say in English, the first sign of a functioning mind is that it can accommodate and appreciate great and conflicting ideas without necessarily believing in them or subscribing to them.

Nevertheless, I built my library on this axiom—that is that books and texts only speak to you if you make an attempt to internalise the content in them. This will involve spending as much time on the text as is required to comprehend the text fully, before you move on to the next book. This axiom, built on the advice of Lenin to the communist students, contrasts completely with one habit of mine—that I buy more books than I can read. The sight, touch and smell of a new book just force me to break lose from all the financial constraints that a middle class person like me may feel and face on daily basis.

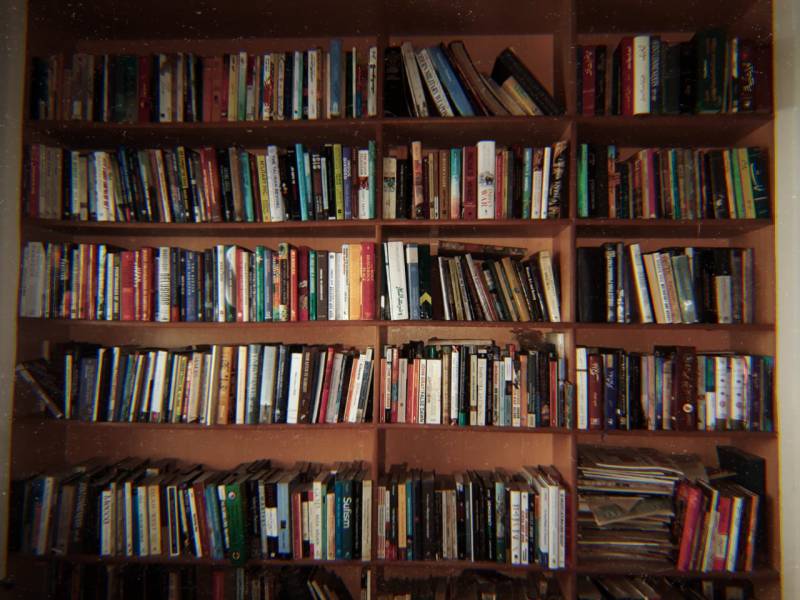

The result of 27 years of breaking and violating this financial discipline is a personal library that houses more than 6000 books---books of every type, history, religion, philosophy, fiction, security affairs, international relations, wars, conflicts, psychology, social history, political theory and practice, Marxism, Leninism, Western Liberalism, British empire, Islamic history and Indian history and the list is endless.

Let me tell you how I select a book. First thing that attracts me is the name of the author. For instance, nowadays I don’t miss a book if it is authored by writers such as Karen Armstrong, Michael Cook, Nail Ferguson, Robert Kaplan, Peter Watson, Ayesha Jalal, Romila Thapar and few others. Second thing that attracts me is a combination of good subject and name of established publishing house. For instance if the subject of the book attracts me and if it is published by Cambridge University press, I will straight away go for the book. On the other hand if the subject attracts me and the publishing house is an unknown one, I will think thousands times before buying the book. The names of the leading publishing houses, which will automatic make me go for the book are Penguin, Oxford University Press, Rupa Publications of India, Allen Lane, Hurst Publications of London and few others. Unfortunately, none of Pakistan based publishing house is credible enough to be included in the list.

I sometimes joke with my friends that if I am afforded a life free of worries for livelihood I will spend rest of my life studying the history of ideas—ideas of every type, religious ideas, philosophical ideas, social and political ideas. The books of fascinating historian of ideas Peter Watson adorn the shelves of my personal library. He is fascinating because he is equally capable of describing ideas contained in complex religious texts as well as the pots discovered from some ancient archaeological sites. He is also fascinating because of the diverse range of ideas he has described and covered in his books—philosophical, religious, historical, scientific, social and economic. He is equally capable of deciphering ideas from the music, dance, painting and sculpture.

Another book about ideas that adorns my shelves and that is my favorite is the 'Formative Period of Islamic Thought' by well-known Orientalist, Montogomery Watt. He simply takes you on a tour of philosophical and religious ideas that developed in the formative years of Islamic history.

This book is fascinating because it debunks the popular perception that Islamic thought and Islamic orthodoxy is some static phenomenon. Rather book presents Islamic Thought as a result of vibrant evolutionary process that is spread of centuries. There is a very organic relation, according to the book, between Heterodoxy and Orthodoxy in Islamic history.

My library is a collection of books that came to me as a result of two of my obsessions—my obsession with Indian history and Islamic history and how these two histories converge into one stream, at certain point of time and intellectual space, in the lands that is called sub-continent, the other obsession is to understand religion, especially Islam, as a political system or political idea, and contrast this with the modern political philosophies and systems, for which 18th, 19th and 20 centuries were the formative period.

My first obsession: Convergence of Islamic and Indian history has produced a flowering of culture that is extremely fascinating to say the least. It is very unfortunate that we in Pakistan have severed our relations with this fascinating cultural heritage that resulted from convergence of Islamic and Indian history in the sub-continent because we as a state and society leaned heavily towards revivalist interpretation of Islam that was the product of colonial era.

The synthesize of Islamic and India culture in history produced art, literature, music, dance and philosophical and religious concepts that should have been rightly claimed by Pakistani state and society that styled themselves as the inheritors of Muslim traditions in Indian sub-continent.

So this obsession has resulted in a collection of books on Indian history and Islamic tradition in India that occupy two long shelves in my library. Islam as history can disabuse our society from the menace of extremism—intellectual endeavor to discover the trajectory of Islam to become a world religion, encompassing countless number of ethnic nationalities and racial groups, will make our youth understand how far removed extremism is from the true, assimilative and flexible nature of Islam.

The other obsession of comparing religions as a political system with modern political philosophies took me into deeper intellectual endeavors as this matched perfectly with my profession—I am a journalist and have a 27 years long career of writing on political affairs. So shelves after shelves in my library are filled with books on Islamic political thought—both modern and ancient—and modern political systems like Marxism, liberalism, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, John Staurt Mills and others.

Ironically, there is a very little understanding of the fact that political axioms of Islam have always been interpreted in the light of political, social and philosophical ideas of any given era. For instance, Greek and Iranian political thought greatly influenced initial years of political thinking after military expansion brought Islamic governments to Fertile Crescent. Muslims were politically and militarily dominant and therefore didn’t have any complex in learning from other people. Even in sub-continent in post-Mughal period Muslim intellectuals made many attempts to interpret Islam’s political and social principles in the light of socialist thoughts that came to dominate the intellectual horizons of the world after 19th century.

It was only the Cold War dynamics of world politics, which prevented Muslim world from embracing the socialist principles—that match with the egalitarian nature of Islam—to make it part of their intellectual and political tradition.

My second obsession has brought my library to a situation where all the shelves in it are fully packed—and yet intellectually I think that I still have a long way to go. Although financial constraints have failed to contain my obsession, providing more room for more books is an impossible task in the small 10 marla house that I constructed in 2012. I am lobbying with my wife these days to make her vacate the drawing room so that I can shift my library into relatively wider room in the house.

For that to happen, I believe, I will have to increase the commercial value of whatever I have learnt from these books during the past 27 years. The anti-intellectual trends in our society don’t allow me to be much optimist in this regard.

Does this make me a Marxist-Leninist? No, it doesn’t. I am not a Marxist pure and simple. As they say in English, the first sign of a functioning mind is that it can accommodate and appreciate great and conflicting ideas without necessarily believing in them or subscribing to them.

Nevertheless, I built my library on this axiom—that is that books and texts only speak to you if you make an attempt to internalise the content in them. This will involve spending as much time on the text as is required to comprehend the text fully, before you move on to the next book. This axiom, built on the advice of Lenin to the communist students, contrasts completely with one habit of mine—that I buy more books than I can read. The sight, touch and smell of a new book just force me to break lose from all the financial constraints that a middle class person like me may feel and face on daily basis.

The result of 27 years of breaking and violating this financial discipline is a personal library that houses more than 6000 books---books of every type, history, religion, philosophy, fiction, security affairs, international relations, wars, conflicts, psychology, social history, political theory and practice, Marxism, Leninism, Western Liberalism, British empire, Islamic history and Indian history and the list is endless.

Let me tell you how I select a book. First thing that attracts me is the name of the author. For instance, nowadays I don’t miss a book if it is authored by writers such as Karen Armstrong, Michael Cook, Nail Ferguson, Robert Kaplan, Peter Watson, Ayesha Jalal, Romila Thapar and few others. Second thing that attracts me is a combination of good subject and name of established publishing house. For instance if the subject of the book attracts me and if it is published by Cambridge University press, I will straight away go for the book. On the other hand if the subject attracts me and the publishing house is an unknown one, I will think thousands times before buying the book. The names of the leading publishing houses, which will automatic make me go for the book are Penguin, Oxford University Press, Rupa Publications of India, Allen Lane, Hurst Publications of London and few others. Unfortunately, none of Pakistan based publishing house is credible enough to be included in the list.

I sometimes joke with my friends that if I am afforded a life free of worries for livelihood I will spend rest of my life studying the history of ideas—ideas of every type, religious ideas, philosophical ideas, social and political ideas. The books of fascinating historian of ideas Peter Watson adorn the shelves of my personal library. He is fascinating because he is equally capable of describing ideas contained in complex religious texts as well as the pots discovered from some ancient archaeological sites. He is also fascinating because of the diverse range of ideas he has described and covered in his books—philosophical, religious, historical, scientific, social and economic. He is equally capable of deciphering ideas from the music, dance, painting and sculpture.

Another book about ideas that adorns my shelves and that is my favorite is the 'Formative Period of Islamic Thought' by well-known Orientalist, Montogomery Watt. He simply takes you on a tour of philosophical and religious ideas that developed in the formative years of Islamic history.

This book is fascinating because it debunks the popular perception that Islamic thought and Islamic orthodoxy is some static phenomenon. Rather book presents Islamic Thought as a result of vibrant evolutionary process that is spread of centuries. There is a very organic relation, according to the book, between Heterodoxy and Orthodoxy in Islamic history.

My library is a collection of books that came to me as a result of two of my obsessions—my obsession with Indian history and Islamic history and how these two histories converge into one stream, at certain point of time and intellectual space, in the lands that is called sub-continent, the other obsession is to understand religion, especially Islam, as a political system or political idea, and contrast this with the modern political philosophies and systems, for which 18th, 19th and 20 centuries were the formative period.

My first obsession: Convergence of Islamic and Indian history has produced a flowering of culture that is extremely fascinating to say the least. It is very unfortunate that we in Pakistan have severed our relations with this fascinating cultural heritage that resulted from convergence of Islamic and Indian history in the sub-continent because we as a state and society leaned heavily towards revivalist interpretation of Islam that was the product of colonial era.

The synthesize of Islamic and India culture in history produced art, literature, music, dance and philosophical and religious concepts that should have been rightly claimed by Pakistani state and society that styled themselves as the inheritors of Muslim traditions in Indian sub-continent.

So this obsession has resulted in a collection of books on Indian history and Islamic tradition in India that occupy two long shelves in my library. Islam as history can disabuse our society from the menace of extremism—intellectual endeavor to discover the trajectory of Islam to become a world religion, encompassing countless number of ethnic nationalities and racial groups, will make our youth understand how far removed extremism is from the true, assimilative and flexible nature of Islam.

The other obsession of comparing religions as a political system with modern political philosophies took me into deeper intellectual endeavors as this matched perfectly with my profession—I am a journalist and have a 27 years long career of writing on political affairs. So shelves after shelves in my library are filled with books on Islamic political thought—both modern and ancient—and modern political systems like Marxism, liberalism, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, John Staurt Mills and others.

Ironically, there is a very little understanding of the fact that political axioms of Islam have always been interpreted in the light of political, social and philosophical ideas of any given era. For instance, Greek and Iranian political thought greatly influenced initial years of political thinking after military expansion brought Islamic governments to Fertile Crescent. Muslims were politically and militarily dominant and therefore didn’t have any complex in learning from other people. Even in sub-continent in post-Mughal period Muslim intellectuals made many attempts to interpret Islam’s political and social principles in the light of socialist thoughts that came to dominate the intellectual horizons of the world after 19th century.

It was only the Cold War dynamics of world politics, which prevented Muslim world from embracing the socialist principles—that match with the egalitarian nature of Islam—to make it part of their intellectual and political tradition.

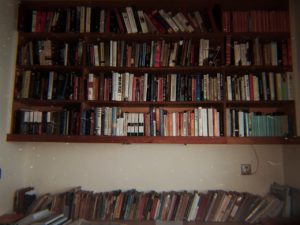

My second obsession has brought my library to a situation where all the shelves in it are fully packed—and yet intellectually I think that I still have a long way to go. Although financial constraints have failed to contain my obsession, providing more room for more books is an impossible task in the small 10 marla house that I constructed in 2012. I am lobbying with my wife these days to make her vacate the drawing room so that I can shift my library into relatively wider room in the house.

For that to happen, I believe, I will have to increase the commercial value of whatever I have learnt from these books during the past 27 years. The anti-intellectual trends in our society don’t allow me to be much optimist in this regard.