Umer Farooq writes that Pakistan's right wing intellectuals failed to grasp the nature of the state they were confronted with, or they were trying to capture, as part of their political struggle. And this proved to be their biggest failure.

Pakistani religious right has always been beset by intellectual incapacity to understand the political concepts that essentially define their politics—it primarily defines as politics what is essentially a kind of moral reformism. Its failure to properly lay down a political ideology that can facilitate the resolution of political conflicts, which exist in the society or to facilitate the management of power relations that are essential for the smoothing functioning of the social and political life in the society, could be taken as its biggest shortcoming.

Essentially, Pakistani right’s intellectuals failed to grasp the nature of the state they were confronted with, or they were trying to capture, as part of their political struggle. And this proved to be their biggest failure. They simply failed in comprehending the nature of post-colonial Pakistani state that Pakistan Muslims inherited as part of British legacy in August 1947. First instance look at the seminal work by Maududi, the foremost ideologue of Pakistani eligious right, which goes with the title—Islamic Riyasat—it’s a collection of speeches, papers, articles and religious tracts.

There is nothing in it to explain and analyze the nature of post-colonial state Pakistan inherited from the British—the book is simply a collection of article explaining what an Islamic state ought to be, however nothing in it explains what Pakistani state actually is, or there is nothing in it about the nature of Pakistan state.

The forces or groups of intellectuals who could have helped Pakistan’s religious right in understanding or comprehending the true nature of Post-colonial Pakistani state became the main political or ideological rivals of Pakistani right.

For instance in the 1950, 1960 and 1970s there were intellectual of Pakistani Left who were explaining the true nature of post-colonial state that Pakistan was, to the educated classes and general masses in Pakistani society through their writings.

These included Hamza Alvi and Abdullah Malik to name a few. Pakistani Right, right from the very start fell out with these intellectuals and the political forces, which had embraced their thoughts about the nature of Pakistani state. Pakistan Right, instead, started to preach a kind of moral reformism to the masses that has nothing to do with politics or the management of power relations in a society beset with political, social and religious conflicts. This included enforcement of strict moral code and observance of religious rituals in the daily life of the people.

The intellectual who came after Mudaudi also hardly made any efforts to understand or analyze the nature of Post-Colonial Pakistan State—a state which was causing practical problems for the continued viability of political community that Muslims of South Asia formed as part of a struggle to win a separate homeland for themselves.

Pakistani Right was more interested making the state recite the “Kalama” and enter the fold of Islam, instead of comprehending the true nature of the state, which was deeply callous, anti-democratic and directed towards revenue collection and maintaining strict administrative control of the society through the use of steel frame and coercive tools that the British have left behind.

For instance the main party of Religious Right, Jamat-e-Islami used to tell its workers and activists before the enactment of 1956 Constitution that they should not take the oath of allegiance to the state as it is not fully a “Islamic state”—by that time country was still governed in accordance with the British made Government of India Act 1935. After the 1956 Constitution clearly declared Pakistan as Islamic Republic and included certainly Islamic provisions, Maudadi himself allowed his workers to join government service and take oath of allegiance to the state. It was so simple for them. Where as in actuality the things were extremely complex as steel frame and coercive techniques of the state continued to hold sway over the society even after that as the state was still focused on the twin tasks of revenue collection and maintaining law and order through coercive means, which was essentially a legacy of the British.

This association of Islamists with the state, which started in 1956, compelled the religious right to take several anti-people positions. For instance Religious Right got into the statist project of campaigning against regional languages like Bengali and Sindhi—both of which hosts a large corpus of literature belonging to pre-Islamic period in the sub-continent. In the pre-1971 era some of the religious scholars came up with the disingenuous proposal that all Bengali literature should be translated into Arabic and then taught in the schools of East Pakistani. Then Religious scholars’ championing of the cause Urdu as national language—at time spoken by only 9 percent of the population according to first census—proved to be an ultimate anti-people act.

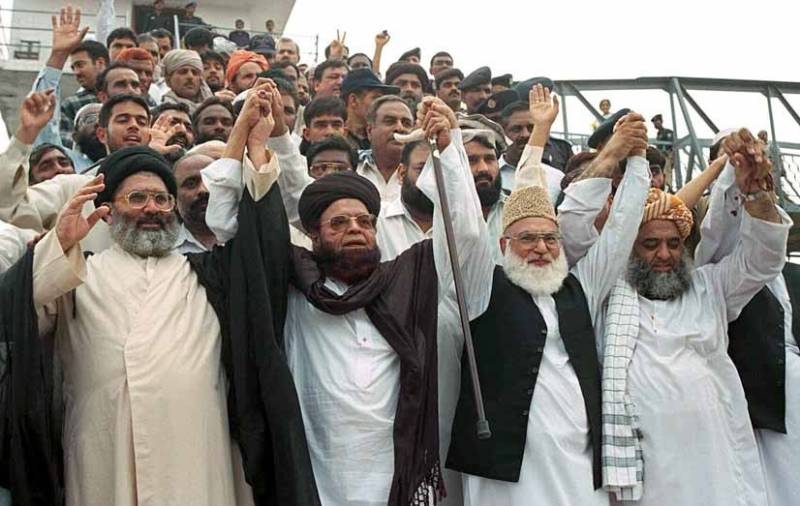

Religious Right then got into championing another statist cause, that is of using armed militants as foreign policy tool into the neighboring countries—and this proved to be the ultimate cause of their fall from grace in Pakistani society and politics. Jamat-e-Islami and Jamiet-e-Ulema Islam especially started supporting the Jihad in Afghanistan that was essentially a project of Pakistani intelligence services, which were partnering with international security establishments.

Later, the Jihad project was extended to the Indian Held Kashmir. The Jihad project essentially proved to be a project of disintegration of these movements as their more radical and more violent offshoots started to crop up. This period also saw the emergence of new radical groups, which completely abandoned the constitutional and political struggle, which the groups of original Religious Right adhered to. These more radical and more violent groups of religious right were part of the state’s project to use violence as a tool of the foreign policy in the region.

The result is one group of original Religious Right—Jamat-e-Islami has become completely irrelevant to Pakistani politics, both at the political level as well as at the ideological level. The other group, Jamiat-e-Ulema Islam, is maintaining its presence in Pakistani politics only on the basis of patronage network that it has constructed on account of its close association with Pakistani state machinery.

It’s true that Pakistani masses are now more inclined towards religious right ideologically and politically—but the traditional parties of the religious right are increasingly losing their relevance to the politics of the country. Now more radical and more violent groups represent the religious right in the political arena.

Pakistani religious right has always been beset by intellectual incapacity to understand the political concepts that essentially define their politics—it primarily defines as politics what is essentially a kind of moral reformism. Its failure to properly lay down a political ideology that can facilitate the resolution of political conflicts, which exist in the society or to facilitate the management of power relations that are essential for the smoothing functioning of the social and political life in the society, could be taken as its biggest shortcoming.

Essentially, Pakistani right’s intellectuals failed to grasp the nature of the state they were confronted with, or they were trying to capture, as part of their political struggle. And this proved to be their biggest failure. They simply failed in comprehending the nature of post-colonial Pakistani state that Pakistan Muslims inherited as part of British legacy in August 1947. First instance look at the seminal work by Maududi, the foremost ideologue of Pakistani eligious right, which goes with the title—Islamic Riyasat—it’s a collection of speeches, papers, articles and religious tracts.

There is nothing in it to explain and analyze the nature of post-colonial state Pakistan inherited from the British—the book is simply a collection of article explaining what an Islamic state ought to be, however nothing in it explains what Pakistani state actually is, or there is nothing in it about the nature of Pakistan state.

The forces or groups of intellectuals who could have helped Pakistan’s religious right in understanding or comprehending the true nature of Post-colonial Pakistani state became the main political or ideological rivals of Pakistani right.

For instance in the 1950, 1960 and 1970s there were intellectual of Pakistani Left who were explaining the true nature of post-colonial state that Pakistan was, to the educated classes and general masses in Pakistani society through their writings.

These included Hamza Alvi and Abdullah Malik to name a few. Pakistani Right, right from the very start fell out with these intellectuals and the political forces, which had embraced their thoughts about the nature of Pakistani state. Pakistan Right, instead, started to preach a kind of moral reformism to the masses that has nothing to do with politics or the management of power relations in a society beset with political, social and religious conflicts. This included enforcement of strict moral code and observance of religious rituals in the daily life of the people.

The intellectual who came after Mudaudi also hardly made any efforts to understand or analyze the nature of Post-Colonial Pakistan State—a state which was causing practical problems for the continued viability of political community that Muslims of South Asia formed as part of a struggle to win a separate homeland for themselves.

Pakistani Right was more interested making the state recite the “Kalama” and enter the fold of Islam, instead of comprehending the true nature of the state, which was deeply callous, anti-democratic and directed towards revenue collection and maintaining strict administrative control of the society through the use of steel frame and coercive tools that the British have left behind.

For instance the main party of Religious Right, Jamat-e-Islami used to tell its workers and activists before the enactment of 1956 Constitution that they should not take the oath of allegiance to the state as it is not fully a “Islamic state”—by that time country was still governed in accordance with the British made Government of India Act 1935. After the 1956 Constitution clearly declared Pakistan as Islamic Republic and included certainly Islamic provisions, Maudadi himself allowed his workers to join government service and take oath of allegiance to the state. It was so simple for them. Where as in actuality the things were extremely complex as steel frame and coercive techniques of the state continued to hold sway over the society even after that as the state was still focused on the twin tasks of revenue collection and maintaining law and order through coercive means, which was essentially a legacy of the British.

This association of Islamists with the state, which started in 1956, compelled the religious right to take several anti-people positions. For instance Religious Right got into the statist project of campaigning against regional languages like Bengali and Sindhi—both of which hosts a large corpus of literature belonging to pre-Islamic period in the sub-continent. In the pre-1971 era some of the religious scholars came up with the disingenuous proposal that all Bengali literature should be translated into Arabic and then taught in the schools of East Pakistani. Then Religious scholars’ championing of the cause Urdu as national language—at time spoken by only 9 percent of the population according to first census—proved to be an ultimate anti-people act.

Religious Right then got into championing another statist cause, that is of using armed militants as foreign policy tool into the neighboring countries—and this proved to be the ultimate cause of their fall from grace in Pakistani society and politics. Jamat-e-Islami and Jamiet-e-Ulema Islam especially started supporting the Jihad in Afghanistan that was essentially a project of Pakistani intelligence services, which were partnering with international security establishments.

Later, the Jihad project was extended to the Indian Held Kashmir. The Jihad project essentially proved to be a project of disintegration of these movements as their more radical and more violent offshoots started to crop up. This period also saw the emergence of new radical groups, which completely abandoned the constitutional and political struggle, which the groups of original Religious Right adhered to. These more radical and more violent groups of religious right were part of the state’s project to use violence as a tool of the foreign policy in the region.

The result is one group of original Religious Right—Jamat-e-Islami has become completely irrelevant to Pakistani politics, both at the political level as well as at the ideological level. The other group, Jamiat-e-Ulema Islam, is maintaining its presence in Pakistani politics only on the basis of patronage network that it has constructed on account of its close association with Pakistani state machinery.

It’s true that Pakistani masses are now more inclined towards religious right ideologically and politically—but the traditional parties of the religious right are increasingly losing their relevance to the politics of the country. Now more radical and more violent groups represent the religious right in the political arena.