Dr. Sara Gilani, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, says that instead of creating panic, the best way to deal with the outbreak of coronavirus is effective surveillance, containment and public awareness on simple measures such as frequent hand-washing.

Firstly, let’s have a quick look at where we stand

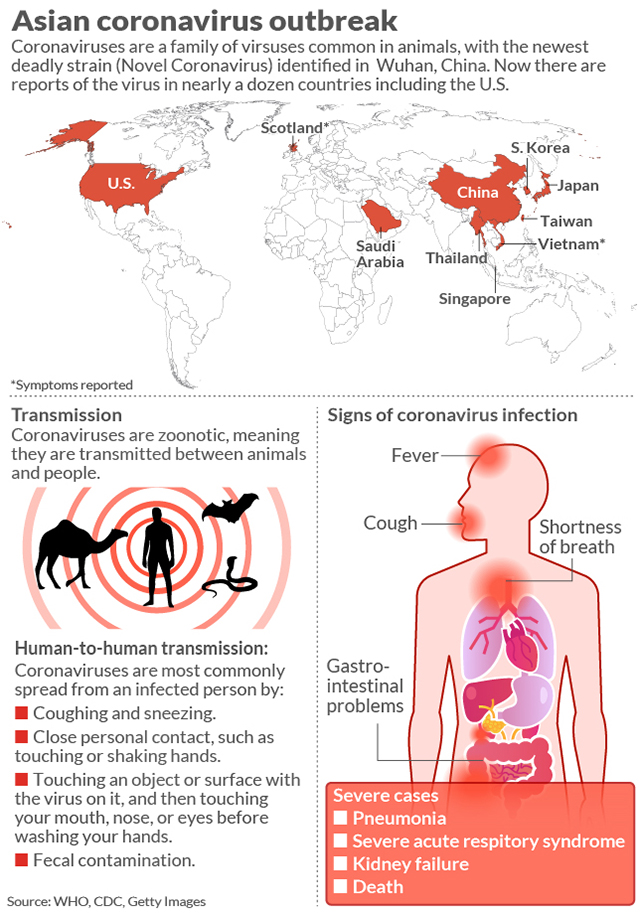

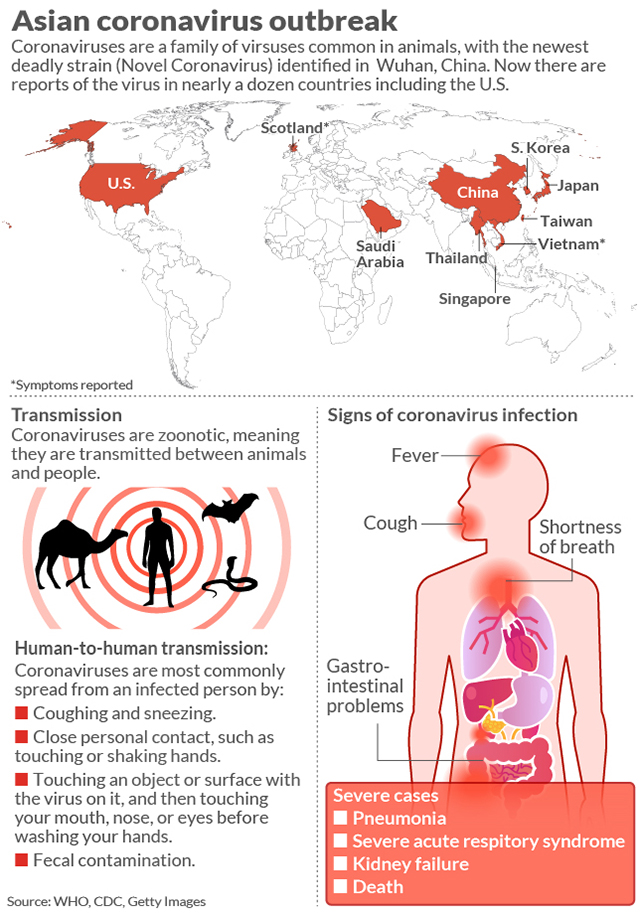

As of 27th February, 2020, there are already over 82,294 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the world - according to WHO figures. The overwhelming majority of cases - 78,630 cases - are reported in only one country, China. The rest – 3,664 cases - are spread out across 46 countries of the world. The first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported in Pakistan on 26th February. They are probably linked to the recent epidemic in Iran. These figures have been calculated using the present WHO-proposed definition, which has two elements: one, the patient must have severe acute respiratory infection and, two, the patient must either have a history of travel to an area where there is an active outbreak of COVID-19 or contact with a probable or confirmed case of COVID-19.

Second, what is COVID-19 and just how dangerous is it?

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses which may cause illness in animals or humans. In humans, several coronaviruses are known to cause respiratory infections ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). The most recently discovered coronavirus causes coronavirus disease COVID-19. Contrary to the popular misconception, not everyone who is infected will die. From the limited data available, its case fatality rate is estimated around 3%. Most people who have died from it thus far are those who were severely ill and admitted in the hospitals. It is important to note that these statistics vary as the epidemic progresses.

Third, why is there such a massive global media hype around Coronavirus epidemic?

Third, why is there such a massive global media hype around Coronavirus epidemic?

The hype is primarily a result of WHO’s decision, taken on 30th January,2020 to declare this as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Once that happens, it is only natural that the matter would occupy airwaves in all countries. The media hype is useful to the extent it helps provide information to citizens on techniques of prevention. If people are aware of the signs and symptoms of the disease, they are more likely to report suspected infections, which in turns allows governments to respond more effectively. Preventive efforts are most effective in the early stages; thus the frantic efforts presently being made by governments. However, media hype can also create unnecessary stress and fan misconceptions.

Finally, what’s recommended and what’s not?

Public health experts around the globe advocate effective surveillance as the top most strategy that is applicable to all countries. Surveillance is best done in a fear-free environment where potential patients voluntarily opt for rapid reporting and testing of suspected cases. Surveillance needs to be coupled with strategies of containment, ie. isolation/quarantine of confirmed cases and active contact tracing and management. Creating awareness about general hygiene measures i.e. frequent hand washing and etiquettes of sneezing and coughing to avoid droplet transmission, is also very important.

At this stage, WHO does not recommend travel or trade restrictions based on current situation as it can create undue fear. When people are afraid, they try to hide their symptoms or avoid reporting to health facilities. Strategies of mitigation like avoiding big congregations and shutting down schools have also not yet been recommended. But authorities can, and indeed should, tailor measures according to the prevailing situation in their respective countries.

In all emerging infections, the people most at risk, unfortunately, are health workers. They can inadvertently transmit it to their colleagues, families and communities leading to amplification of the outbreaks. Thus it is very essential that the health workers use proper recommended protective measures and follow the isolation and contact tracing procedures if they develop symptoms.

Finally, under no circumstances should the personal identity and contact information of patients be made public. This little mistake, which has already happened in Pakistan at the highest levels of government and media, must not be repeated. This is not only because it is unethical but also because it can discourage other potential suspected patients from reporting. And lack of reporting is perhaps the single biggest challenge that the global public health authorities face when trying to fight any emerging disease.

Firstly, let’s have a quick look at where we stand

As of 27th February, 2020, there are already over 82,294 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the world - according to WHO figures. The overwhelming majority of cases - 78,630 cases - are reported in only one country, China. The rest – 3,664 cases - are spread out across 46 countries of the world. The first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported in Pakistan on 26th February. They are probably linked to the recent epidemic in Iran. These figures have been calculated using the present WHO-proposed definition, which has two elements: one, the patient must have severe acute respiratory infection and, two, the patient must either have a history of travel to an area where there is an active outbreak of COVID-19 or contact with a probable or confirmed case of COVID-19.

Second, what is COVID-19 and just how dangerous is it?

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses which may cause illness in animals or humans. In humans, several coronaviruses are known to cause respiratory infections ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). The most recently discovered coronavirus causes coronavirus disease COVID-19. Contrary to the popular misconception, not everyone who is infected will die. From the limited data available, its case fatality rate is estimated around 3%. Most people who have died from it thus far are those who were severely ill and admitted in the hospitals. It is important to note that these statistics vary as the epidemic progresses.

Third, why is there such a massive global media hype around Coronavirus epidemic?

Third, why is there such a massive global media hype around Coronavirus epidemic? The hype is primarily a result of WHO’s decision, taken on 30th January,2020 to declare this as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Once that happens, it is only natural that the matter would occupy airwaves in all countries. The media hype is useful to the extent it helps provide information to citizens on techniques of prevention. If people are aware of the signs and symptoms of the disease, they are more likely to report suspected infections, which in turns allows governments to respond more effectively. Preventive efforts are most effective in the early stages; thus the frantic efforts presently being made by governments. However, media hype can also create unnecessary stress and fan misconceptions.

Finally, what’s recommended and what’s not?

Public health experts around the globe advocate effective surveillance as the top most strategy that is applicable to all countries. Surveillance is best done in a fear-free environment where potential patients voluntarily opt for rapid reporting and testing of suspected cases. Surveillance needs to be coupled with strategies of containment, ie. isolation/quarantine of confirmed cases and active contact tracing and management. Creating awareness about general hygiene measures i.e. frequent hand washing and etiquettes of sneezing and coughing to avoid droplet transmission, is also very important.

At this stage, WHO does not recommend travel or trade restrictions based on current situation as it can create undue fear. When people are afraid, they try to hide their symptoms or avoid reporting to health facilities. Strategies of mitigation like avoiding big congregations and shutting down schools have also not yet been recommended. But authorities can, and indeed should, tailor measures according to the prevailing situation in their respective countries.

In all emerging infections, the people most at risk, unfortunately, are health workers. They can inadvertently transmit it to their colleagues, families and communities leading to amplification of the outbreaks. Thus it is very essential that the health workers use proper recommended protective measures and follow the isolation and contact tracing procedures if they develop symptoms.

Finally, under no circumstances should the personal identity and contact information of patients be made public. This little mistake, which has already happened in Pakistan at the highest levels of government and media, must not be repeated. This is not only because it is unethical but also because it can discourage other potential suspected patients from reporting. And lack of reporting is perhaps the single biggest challenge that the global public health authorities face when trying to fight any emerging disease.