The ‘communal’ impulse and justification of India’s partition (into two separate nations) was originally formed by Hindu nationalists and was adopted much later by the likes of Jinnah, writes Nadeem F. Paracha.

The narrative behind the creation of Pakistan which sees its emergence as an entity that was to evolve into becoming a theocracy, was largely constructed from the late 1970s onward by a state and nationalist intelligentsia reacting to the East Pakistan debacle in 1971. They saw the parting of Pakistan’s erstwhile eastern wing as a consequence of the failures of ‘modernist/secular’ maneuvers of Pakistan’s ruling elites between 1947 and 1971.

The interesting bit is that this post-1971 narrative of Pakistan’s creation is also accepted by Hindu nationalists, mainly to supplement and justify their own theocratic and communal disposition and their subsequent hostility towards the Muslim other.

In most discussions in India, Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s ‘Two-Nation Theory’, which became the basis of the partition of India in 1947, is often lambasted as being communal in nature.

The theory suggested that the Hindus and Muslims of India were two separate nations that needed their own geopolitical abodes in which they could govern their lives according to their distinct cultural bearings.

But most Indian historians (both on the left and the right) have largely repressed the rather confounding fact that the Two-Nation Theory was not a spontaneous communal brainwave of Muslim leaders. It had actually been developed and forced upon them by Hindu nationalists.

Jinnah was quite aware of exactly how the Two-Nation Theory, which he eventually championed, actually came about. He was correct to assert that it was originally formed by Hindu nationalists as a way to assert their political and social agendas (mainly against the Muslims).

Jinnah finally accepted it for the Muslims after he witnessed Hindu nationalist tendencies emerging within sections of the ‘secular’ Indian Congress Party (INC) as well.

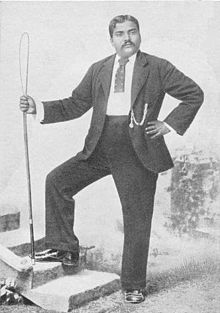

Writer and intellectual, Raj Narayan Basu, established a society in the mid-19th century to promote nationalist feelings among the Hindus of India. In one of his speeches to the society Basu said that ‘Hinduism, despite its caste system, presented a much higher social idealism than that of Christian or Muslim civilizations.’[1] He also formed an organization called Bharat Dharma Mahamandal through which he aspired to ‘establish an ‘Aryan nation’ in India.[2]

In 1872, playwright and poet, Nagopal Mitra, wrote in an article that ‘the Hindus are destined to become a religious nation.’[3] He had also established an annual ‘Hindu mela’ to promote Hindu culture. When a reader asked why he was doing this, he replied, ‘because Hindus are a nation.’ He then added: ‘The basis of national unity in India is the Hindu religion. Hindu nationality embraces all the Hindus of India irrespective of their locality or language. [4]

In 1882, Bankimchandra Chatterjee published a Bengali novel, Anandamath. The novel’s plot is set in the background of the 18th Century revolt in Bengal of Hindu ascetics against the British East India Company. In the novel, Chatterjee included a poem, Vende Mataram (Hail to the Mother) that he had penned in the 1870s. The poem was turned into a marching song by Indian National Congress (INC) in the early 20th century. In 1947, the first two verses of the poem were included in the Indian national anthem. The poem was one of the first to inspire the image of India as a mother. It also went on to inspire Hindu nationalists.

In 1883, a year after the publication of Anandamath, Muslim reformist, scholar and founder of South Asian ‘Muslim modernism’, Syed Ahmad Khan told a gathering of Muslim intellectuals in Patna: ‘In India there live two prominent nations which are distinguished by the names of Hindus and Muslims. Just as a man has some principal organs, similarly these two nations are like the principal limbs of India.’[5] However, his tone became harsher after the formation of the INC which he saw as an overwhelmingly Hindu outfit. In an 1887 speech, he said: ‘Suppose that the British were to leave India. Then who would be rulers of India? Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations, Muslim and Hindu, could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not.’[6]

In 1906, in response to the creation of INC, the All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed. It emerged as an early political expression of the gradual growth of a Muslim middle-class in India. The party was inspired by the academic and social activism of Syed Ahmad Khan who was one of the first major exponents of ‘Muslim modernism’ in India. The party’s first manifesto looked to safeguard the rights of India’s Muslims.

In 1908, a prominent leader of the Hindu evangelical outfit, the Arya Samaj, declared that ‘Hindus and Muslims of India were two different people with irreconcilable worldviews, sense of history and destiny.[7]

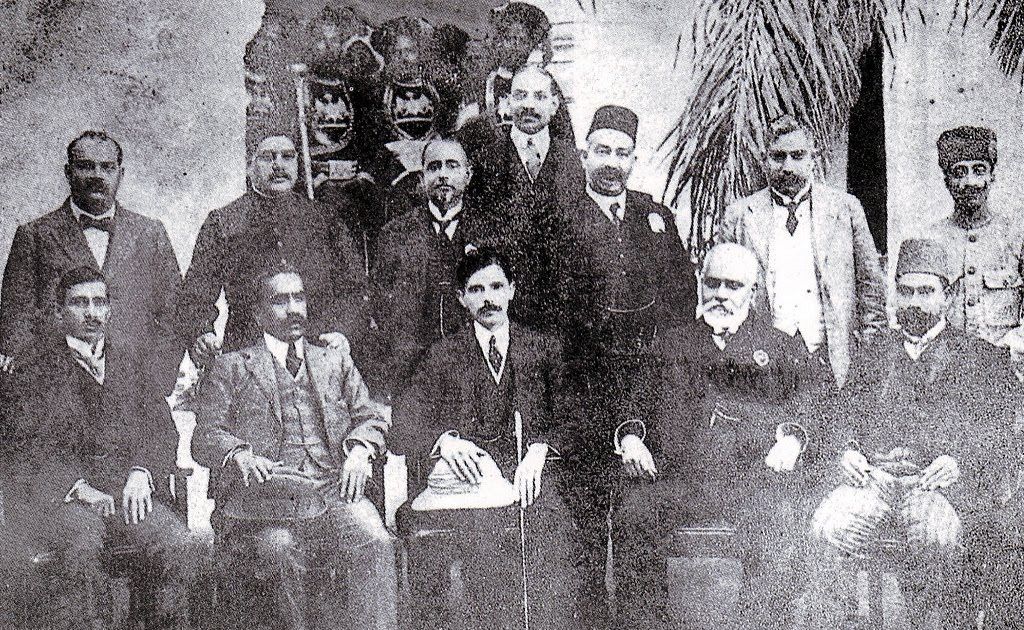

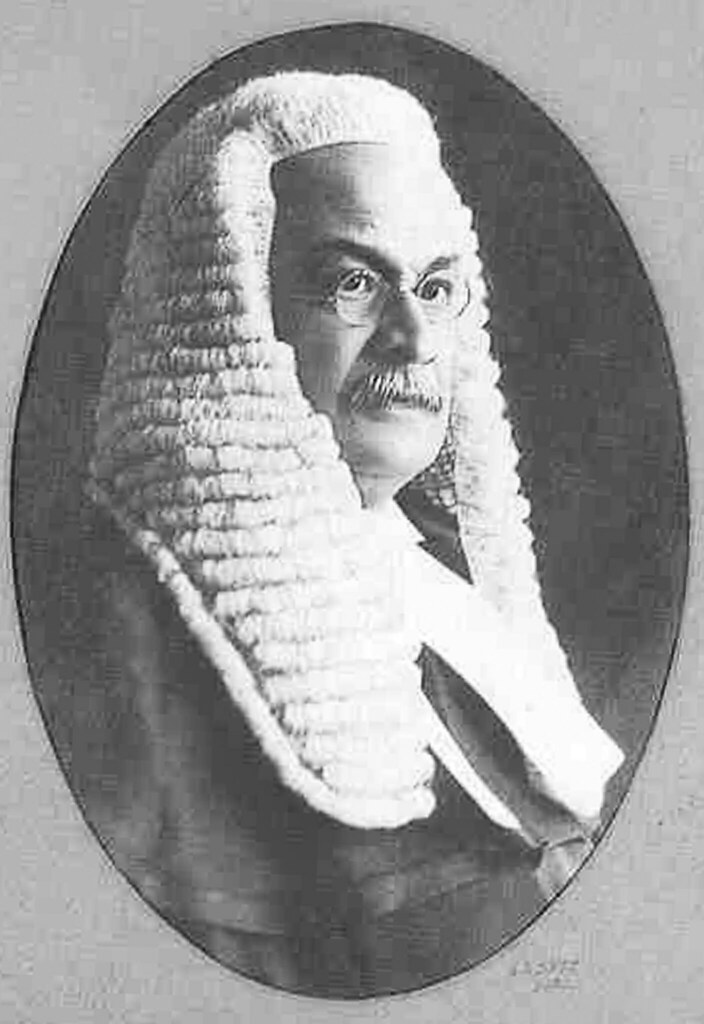

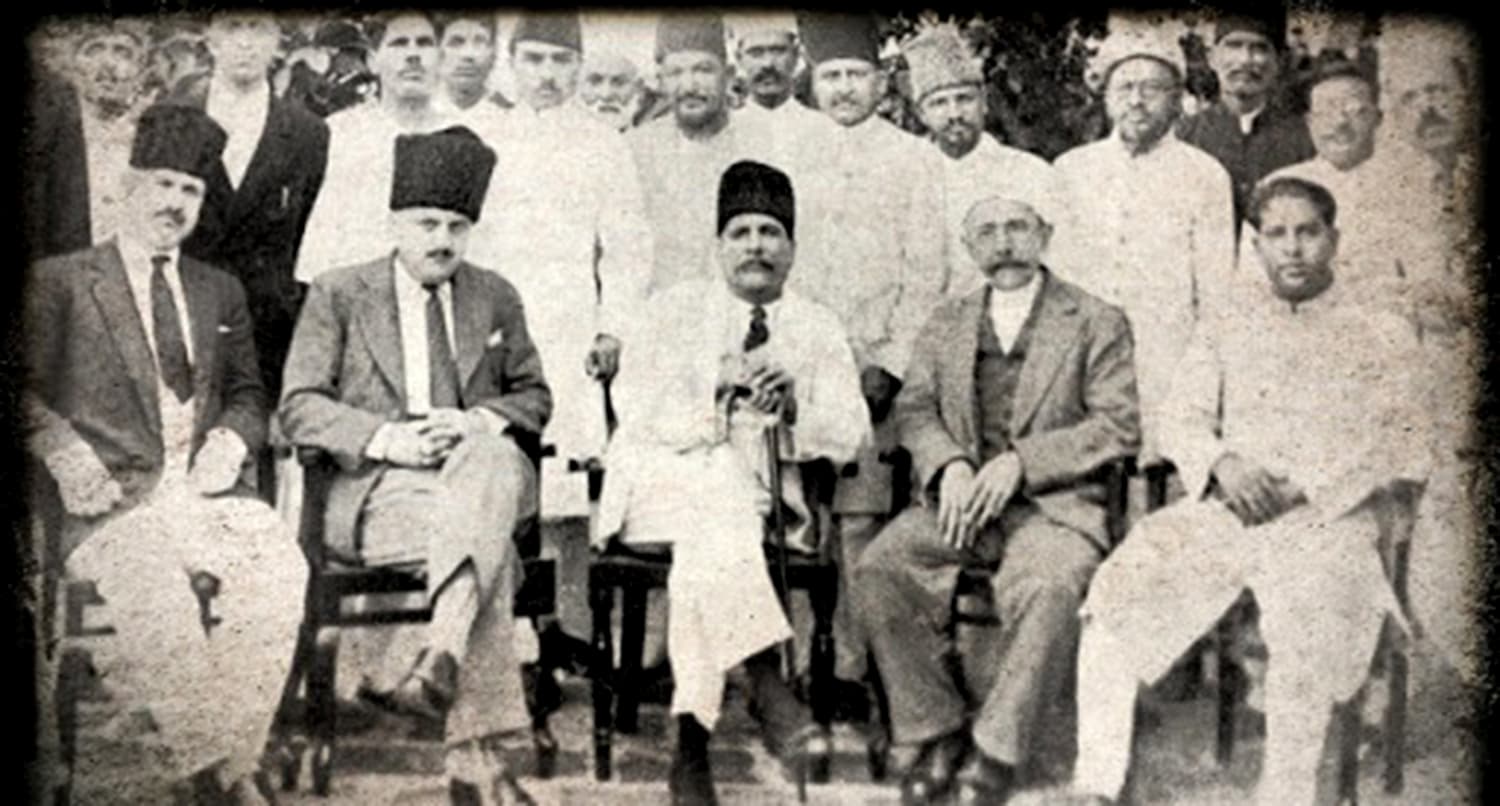

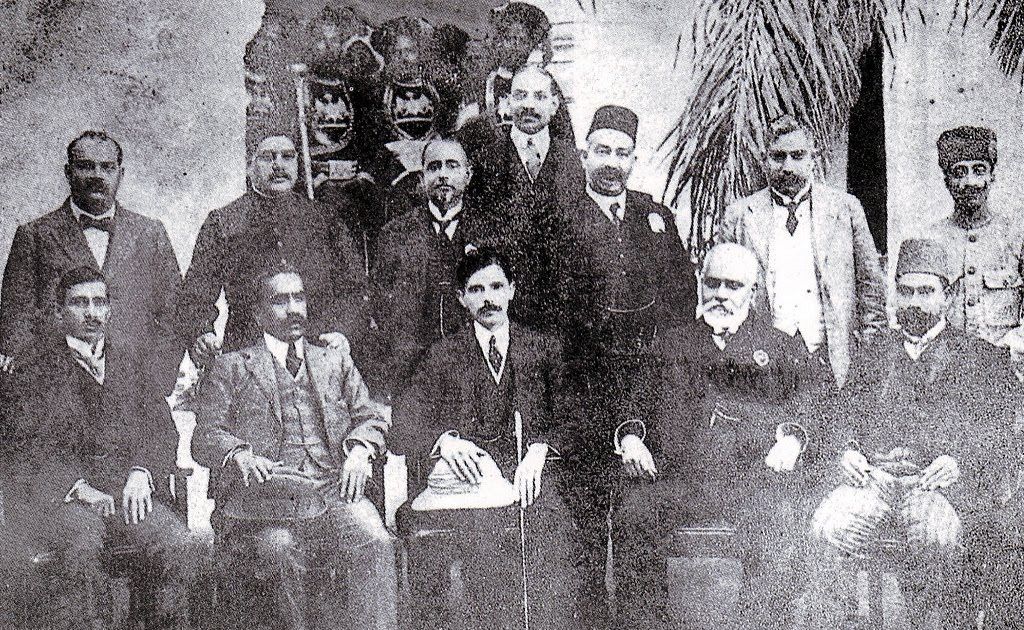

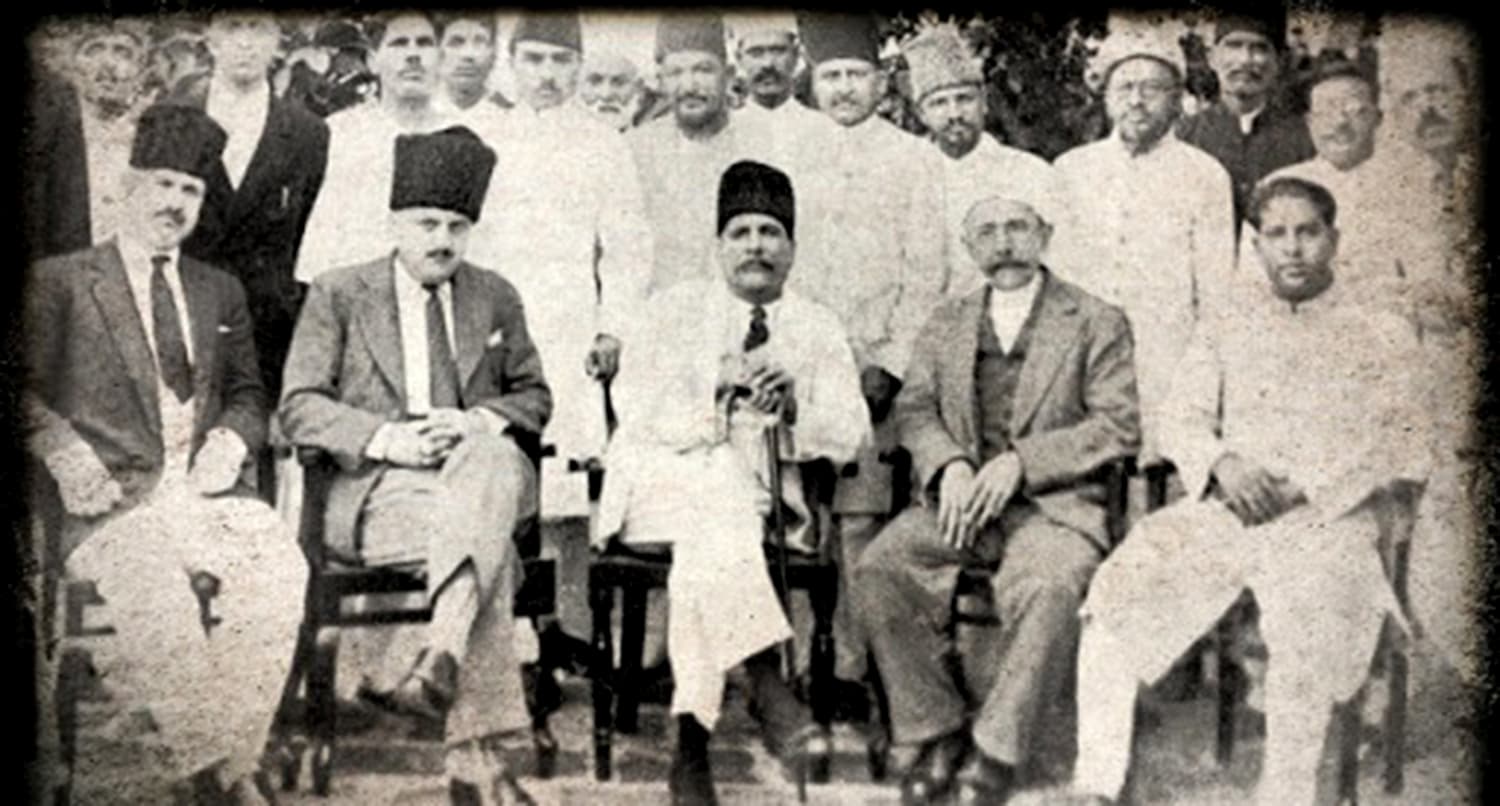

In 1916, AIML agreed to work with the INC in demanding Indian autonomy. Former INC member, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (sitting third from left), a barrister and liberal-democrat, who had joined the AIML, was hailed as the ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.’[8]

In 1923, Hindu nationalist ideologue, V. Savarkar, published a pamphlet, The Essentials of Hindutva. Savarkar explained the term ‘Hindutva’ as ‘Hinduness’ or a combination of qualities and conditions that make a person a Hindu. He saw India as a ‘Hindu rashtra’ (Hindu nation). Ironically, Savarkar was an atheist, so in his pamphlet he eschewed Hindu theology and instead explained Hinduism as an ethnic, cultural and political identity. To him, a Hindu was a person born in India and followed Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism or Sikhism – and/or faiths that were born in India. To Savarkar Islam and Christianity were thus ‘alien faiths’ and there was no place for them in the Hindu rashtra.

In 1923, BS Moonjie, an INC leader who later joined the Hindu Mahsabha (which became the unofficial Hindu nationalist wing of INC) told a gathering in Oudh: "Just as England belongs to the English, France to the French, and Germany to the Germans, India belongs to the Hindus. If Hindus get organized, they can humble the English and their stooges, the Muslims. The Hindus henceforth can create their own world which will prosper through shuddhi (the act of converting Muslims and Christians to Hinduism).’[9]

In a 1924 speech, a vocal INC member, Lajpat Rai, said: ‘I would suggest that the Punjab should be partitioned into two provinces, the Western Punjab with a large Muslim majority, to be a Muslim-governed province; and the Eastern Punjab, with a large Hindu-Sikh majority, to be a non-Muslim governed province.’[10]

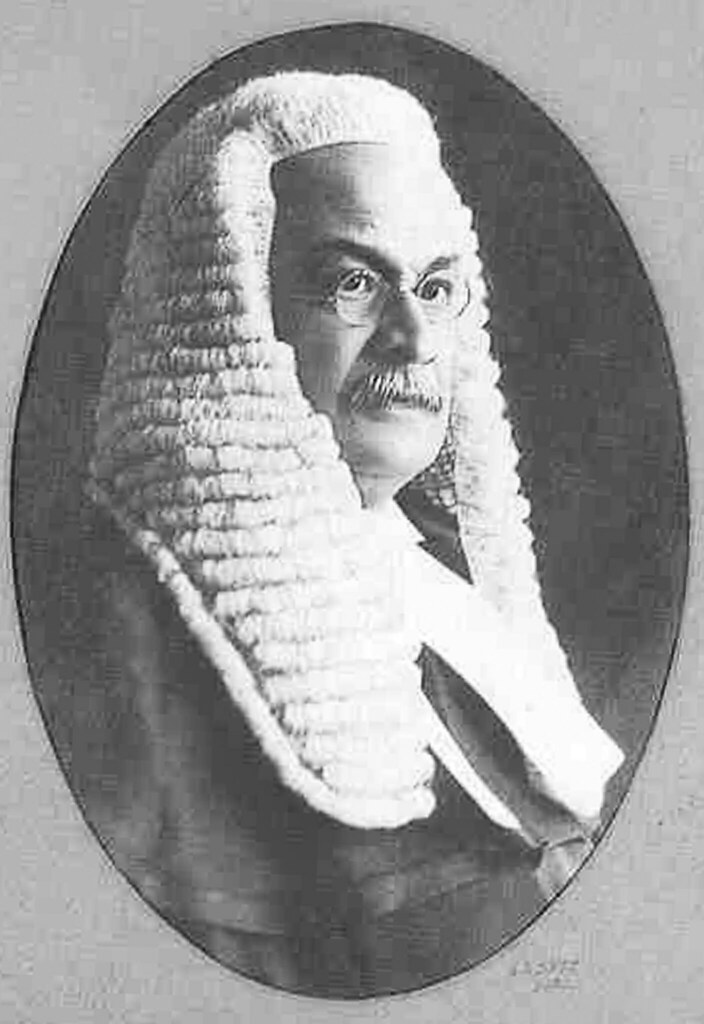

In 1925, a judge from Bengal and member of the AIML, Justice Abdur Rahim, during an AIML session in Aligarh said: ‘The Hindus and Muslims are not two religious sects like the Protestants and Catholics of England, but form two distinct communities of peoples. In India, we (the Muslims) find ourselves in all social matters total aliens when we cross the street and enter that part of the town where our Hindu fellow townsmen live.’[11]

In 1925, as a response to the 1919 creation of the Deobandi Jamiat Ulema Islam Hind (JUIH), some leading Barelvi theologians and pirs formed the All India Sunni Conference (AISC). Pir Jamat Ali Shah was elected as its first president. During the party’s first session, Shah and other AISC leaders declared that, ‘Hindu and Muslims were two different nations.’ The AISC also called for the unity of all Sunni Muslims of India and dismissed those advocating Hindu-Muslim unity.[12]

The same year (1925) Lal Har Dayal, the founder of the ‘revolutionary’ Ghadar Party, issued a statement that read: ‘I declare that the future of the Hindu race and of Hindustan rests on these four pillars: (1) Hindu Sangathan, (2) Hindu Raj, (3) Shuddhi of Muslims, and (4) Conquest and Shuddhi of Afghanistan and the Frontiers. So long as the Hindu Nation does not accomplish these four things, the safety of our children and great grandchildren will be ever in danger, and the safety of Hindu race will be impossible. The Hindu race has but one history, and its institutions are homogenous. But the Muslims and Christians are far removed from the confines of Hindustan, for their religions are alien …’[13]

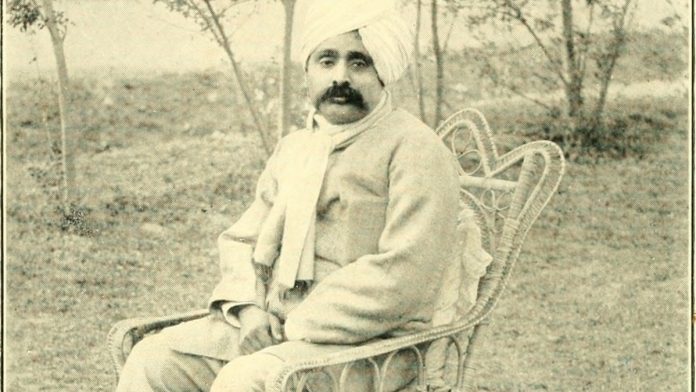

In 1930, philosopher and poet, Muhammad Iqbal became AIML’s president. In an address during a 1930 party conference, he demanded a separate Muslim province within the British Indian federation. In 1933, he said the INC was working for its own benefit and ignoring the rights of India’s Muslims.

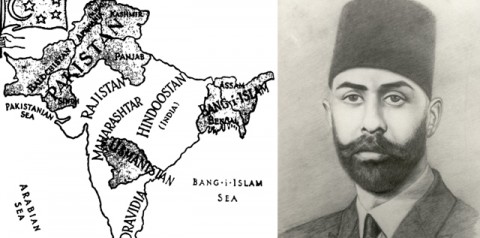

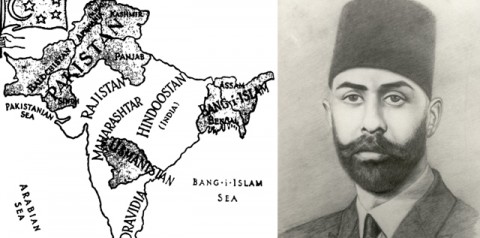

In 1933, Rehmat Ali, a student at UK’s Cambridge University, published a pamphlet, Now or Never, Are We To Live or Perish Forever? In it he urged AIML leaders to call for a separate Muslim state which he called, Pakistan. He also drew a map of it in which he slotted Muslim-majority regions in India as parts of such a country. In 1934 when Ali and some of his colleagues met Jinnah – who was still working to reinvigorate Hindu-Muslim unity – Jinnah told them: ‘My dear boys, don't be in a hurry; let the waters flow and they will find their own level.’[14]

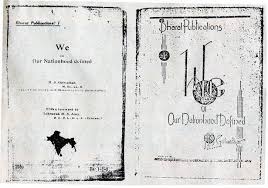

In 1939, the revered leader of the militant Hindu organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) MS Golwalkar published We or Our Nationhood Defined. In it he asserted that the minority communities of India should merge with the Hindu nation or perish. He wrote that non-Hindus in India could not be considered Indian unless they were ‘purified’ (i.e. converted to Hinduism).Golwalkar described the Hindus as being India’s ‘national race’ and pointed at the example of Nazi Germany’s eradication of the Jews as a way to deal with minorities who refused to adapt to the culture of the national race.

In 1940 during a three-day general session of the AIML, the party (now being led by Jinnah) adopted a resolution calling for a separate homeland for Muslims. Jinnah lamented that all his efforts to forge unity between the Hindus and Muslims of India had been undermined by what he thought was INC’s dogmatic attitude and unwillingness to negotiate better terms for India’s Muslims. The resolution, however, did not use the word Pakistan.

In 1943, now committing the AIML to mobilize the Muslims of India to gain their own country, Jinnah made sure to explain that the idea and move for a separate state was thrust upon the AIML by Hindu nationalists and the INC. By now the party had also adopted the name Pakistan. In an April 1943 address, Jinnah told party members: ‘I think you will bear me out that when we passed the Lahore Resolution (in 1940) we had not used the word, Pakistan.’ He then asked, ‘Who gave us this word?’ Cries of ‘Hindus’ rose from the crowd. Jinnah then went on: ‘They (the Hindus) fathered this word upon us.’ [15]

On 14 August 1947, Pakistan came into being.

[1] S. Islam: Muslims Against Partition of India (Pharos, 2017)

[2] Ibid.

[3] C Herman: Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform (Princeton University Press, 2015) p.137.

[4] P. Saha: Hindu-Muslim Relations in a New Perspective (University of Michigan, 2007) p.133.

[5] R. Guha: Makers of Modern India (Harvard University Press, 2011) p.65

[6] The Challenge in South Asia ed. P. Wignaraja; A. Hussain (United Nations Press, 1989) p.201

[7] C. Jaffrelot: Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Princeton University Press, 2009) p.192

[8] IB Wells: Jinnah’s Early Politics (Permanent Black, 2007) p.7

[9] JS. Dhanki: Lala Lajpat Rai and Indian Nationalism (S Publications, 1990). p.378.

[10] The Tribune, Lahore, December 14, 1924, p. 8.

[11] S. Ikram: Indian Muslims and Partition of India (Atlantic Publishers, 1995) p.308.

[12] KK Aziz: A History of the Idea of Pakistan (Vanguard Books, 1987) p.40-41.

[13] BR. Ambedkar: Pakistan or the Partition of India (Maharashtra Government, 1990) p.129.

[14] D. Hiro: The Longest August (PA, 2015) p.69.

[15] C. Cilano: National Identities in Pakistan (Routledge, 2014) p.102.

The narrative behind the creation of Pakistan which sees its emergence as an entity that was to evolve into becoming a theocracy, was largely constructed from the late 1970s onward by a state and nationalist intelligentsia reacting to the East Pakistan debacle in 1971. They saw the parting of Pakistan’s erstwhile eastern wing as a consequence of the failures of ‘modernist/secular’ maneuvers of Pakistan’s ruling elites between 1947 and 1971.

The interesting bit is that this post-1971 narrative of Pakistan’s creation is also accepted by Hindu nationalists, mainly to supplement and justify their own theocratic and communal disposition and their subsequent hostility towards the Muslim other.

In most discussions in India, Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s ‘Two-Nation Theory’, which became the basis of the partition of India in 1947, is often lambasted as being communal in nature.

The theory suggested that the Hindus and Muslims of India were two separate nations that needed their own geopolitical abodes in which they could govern their lives according to their distinct cultural bearings.

But most Indian historians (both on the left and the right) have largely repressed the rather confounding fact that the Two-Nation Theory was not a spontaneous communal brainwave of Muslim leaders. It had actually been developed and forced upon them by Hindu nationalists.

Jinnah was quite aware of exactly how the Two-Nation Theory, which he eventually championed, actually came about. He was correct to assert that it was originally formed by Hindu nationalists as a way to assert their political and social agendas (mainly against the Muslims).

Jinnah finally accepted it for the Muslims after he witnessed Hindu nationalist tendencies emerging within sections of the ‘secular’ Indian Congress Party (INC) as well.

Writer and intellectual, Raj Narayan Basu, established a society in the mid-19th century to promote nationalist feelings among the Hindus of India. In one of his speeches to the society Basu said that ‘Hinduism, despite its caste system, presented a much higher social idealism than that of Christian or Muslim civilizations.’[1] He also formed an organization called Bharat Dharma Mahamandal through which he aspired to ‘establish an ‘Aryan nation’ in India.[2]

In 1872, playwright and poet, Nagopal Mitra, wrote in an article that ‘the Hindus are destined to become a religious nation.’[3] He had also established an annual ‘Hindu mela’ to promote Hindu culture. When a reader asked why he was doing this, he replied, ‘because Hindus are a nation.’ He then added: ‘The basis of national unity in India is the Hindu religion. Hindu nationality embraces all the Hindus of India irrespective of their locality or language. [4]

In 1882, Bankimchandra Chatterjee published a Bengali novel, Anandamath. The novel’s plot is set in the background of the 18th Century revolt in Bengal of Hindu ascetics against the British East India Company. In the novel, Chatterjee included a poem, Vende Mataram (Hail to the Mother) that he had penned in the 1870s. The poem was turned into a marching song by Indian National Congress (INC) in the early 20th century. In 1947, the first two verses of the poem were included in the Indian national anthem. The poem was one of the first to inspire the image of India as a mother. It also went on to inspire Hindu nationalists.

In 1883, a year after the publication of Anandamath, Muslim reformist, scholar and founder of South Asian ‘Muslim modernism’, Syed Ahmad Khan told a gathering of Muslim intellectuals in Patna: ‘In India there live two prominent nations which are distinguished by the names of Hindus and Muslims. Just as a man has some principal organs, similarly these two nations are like the principal limbs of India.’[5] However, his tone became harsher after the formation of the INC which he saw as an overwhelmingly Hindu outfit. In an 1887 speech, he said: ‘Suppose that the British were to leave India. Then who would be rulers of India? Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations, Muslim and Hindu, could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not.’[6]

In 1906, in response to the creation of INC, the All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed. It emerged as an early political expression of the gradual growth of a Muslim middle-class in India. The party was inspired by the academic and social activism of Syed Ahmad Khan who was one of the first major exponents of ‘Muslim modernism’ in India. The party’s first manifesto looked to safeguard the rights of India’s Muslims.

In 1908, a prominent leader of the Hindu evangelical outfit, the Arya Samaj, declared that ‘Hindus and Muslims of India were two different people with irreconcilable worldviews, sense of history and destiny.[7]

In 1916, AIML agreed to work with the INC in demanding Indian autonomy. Former INC member, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (sitting third from left), a barrister and liberal-democrat, who had joined the AIML, was hailed as the ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.’[8]

In 1923, Hindu nationalist ideologue, V. Savarkar, published a pamphlet, The Essentials of Hindutva. Savarkar explained the term ‘Hindutva’ as ‘Hinduness’ or a combination of qualities and conditions that make a person a Hindu. He saw India as a ‘Hindu rashtra’ (Hindu nation). Ironically, Savarkar was an atheist, so in his pamphlet he eschewed Hindu theology and instead explained Hinduism as an ethnic, cultural and political identity. To him, a Hindu was a person born in India and followed Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism or Sikhism – and/or faiths that were born in India. To Savarkar Islam and Christianity were thus ‘alien faiths’ and there was no place for them in the Hindu rashtra.

In 1923, BS Moonjie, an INC leader who later joined the Hindu Mahsabha (which became the unofficial Hindu nationalist wing of INC) told a gathering in Oudh: "Just as England belongs to the English, France to the French, and Germany to the Germans, India belongs to the Hindus. If Hindus get organized, they can humble the English and their stooges, the Muslims. The Hindus henceforth can create their own world which will prosper through shuddhi (the act of converting Muslims and Christians to Hinduism).’[9]

In a 1924 speech, a vocal INC member, Lajpat Rai, said: ‘I would suggest that the Punjab should be partitioned into two provinces, the Western Punjab with a large Muslim majority, to be a Muslim-governed province; and the Eastern Punjab, with a large Hindu-Sikh majority, to be a non-Muslim governed province.’[10]

In 1925, a judge from Bengal and member of the AIML, Justice Abdur Rahim, during an AIML session in Aligarh said: ‘The Hindus and Muslims are not two religious sects like the Protestants and Catholics of England, but form two distinct communities of peoples. In India, we (the Muslims) find ourselves in all social matters total aliens when we cross the street and enter that part of the town where our Hindu fellow townsmen live.’[11]

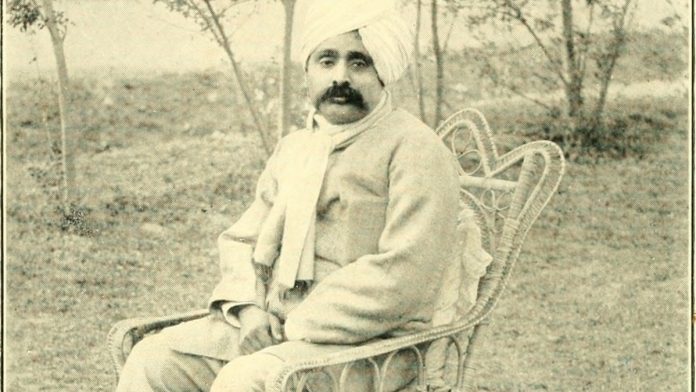

In 1925, as a response to the 1919 creation of the Deobandi Jamiat Ulema Islam Hind (JUIH), some leading Barelvi theologians and pirs formed the All India Sunni Conference (AISC). Pir Jamat Ali Shah was elected as its first president. During the party’s first session, Shah and other AISC leaders declared that, ‘Hindu and Muslims were two different nations.’ The AISC also called for the unity of all Sunni Muslims of India and dismissed those advocating Hindu-Muslim unity.[12]

The same year (1925) Lal Har Dayal, the founder of the ‘revolutionary’ Ghadar Party, issued a statement that read: ‘I declare that the future of the Hindu race and of Hindustan rests on these four pillars: (1) Hindu Sangathan, (2) Hindu Raj, (3) Shuddhi of Muslims, and (4) Conquest and Shuddhi of Afghanistan and the Frontiers. So long as the Hindu Nation does not accomplish these four things, the safety of our children and great grandchildren will be ever in danger, and the safety of Hindu race will be impossible. The Hindu race has but one history, and its institutions are homogenous. But the Muslims and Christians are far removed from the confines of Hindustan, for their religions are alien …’[13]

In 1930, philosopher and poet, Muhammad Iqbal became AIML’s president. In an address during a 1930 party conference, he demanded a separate Muslim province within the British Indian federation. In 1933, he said the INC was working for its own benefit and ignoring the rights of India’s Muslims.

In 1933, Rehmat Ali, a student at UK’s Cambridge University, published a pamphlet, Now or Never, Are We To Live or Perish Forever? In it he urged AIML leaders to call for a separate Muslim state which he called, Pakistan. He also drew a map of it in which he slotted Muslim-majority regions in India as parts of such a country. In 1934 when Ali and some of his colleagues met Jinnah – who was still working to reinvigorate Hindu-Muslim unity – Jinnah told them: ‘My dear boys, don't be in a hurry; let the waters flow and they will find their own level.’[14]

In 1939, the revered leader of the militant Hindu organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) MS Golwalkar published We or Our Nationhood Defined. In it he asserted that the minority communities of India should merge with the Hindu nation or perish. He wrote that non-Hindus in India could not be considered Indian unless they were ‘purified’ (i.e. converted to Hinduism).Golwalkar described the Hindus as being India’s ‘national race’ and pointed at the example of Nazi Germany’s eradication of the Jews as a way to deal with minorities who refused to adapt to the culture of the national race.

In 1940 during a three-day general session of the AIML, the party (now being led by Jinnah) adopted a resolution calling for a separate homeland for Muslims. Jinnah lamented that all his efforts to forge unity between the Hindus and Muslims of India had been undermined by what he thought was INC’s dogmatic attitude and unwillingness to negotiate better terms for India’s Muslims. The resolution, however, did not use the word Pakistan.

In 1943, now committing the AIML to mobilize the Muslims of India to gain their own country, Jinnah made sure to explain that the idea and move for a separate state was thrust upon the AIML by Hindu nationalists and the INC. By now the party had also adopted the name Pakistan. In an April 1943 address, Jinnah told party members: ‘I think you will bear me out that when we passed the Lahore Resolution (in 1940) we had not used the word, Pakistan.’ He then asked, ‘Who gave us this word?’ Cries of ‘Hindus’ rose from the crowd. Jinnah then went on: ‘They (the Hindus) fathered this word upon us.’ [15]

On 14 August 1947, Pakistan came into being.

[1] S. Islam: Muslims Against Partition of India (Pharos, 2017)

[2] Ibid.

[3] C Herman: Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform (Princeton University Press, 2015) p.137.

[4] P. Saha: Hindu-Muslim Relations in a New Perspective (University of Michigan, 2007) p.133.

[5] R. Guha: Makers of Modern India (Harvard University Press, 2011) p.65

[6] The Challenge in South Asia ed. P. Wignaraja; A. Hussain (United Nations Press, 1989) p.201

[7] C. Jaffrelot: Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Princeton University Press, 2009) p.192

[8] IB Wells: Jinnah’s Early Politics (Permanent Black, 2007) p.7

[9] JS. Dhanki: Lala Lajpat Rai and Indian Nationalism (S Publications, 1990). p.378.

[10] The Tribune, Lahore, December 14, 1924, p. 8.

[11] S. Ikram: Indian Muslims and Partition of India (Atlantic Publishers, 1995) p.308.

[12] KK Aziz: A History of the Idea of Pakistan (Vanguard Books, 1987) p.40-41.

[13] BR. Ambedkar: Pakistan or the Partition of India (Maharashtra Government, 1990) p.129.

[14] D. Hiro: The Longest August (PA, 2015) p.69.

[15] C. Cilano: National Identities in Pakistan (Routledge, 2014) p.102.