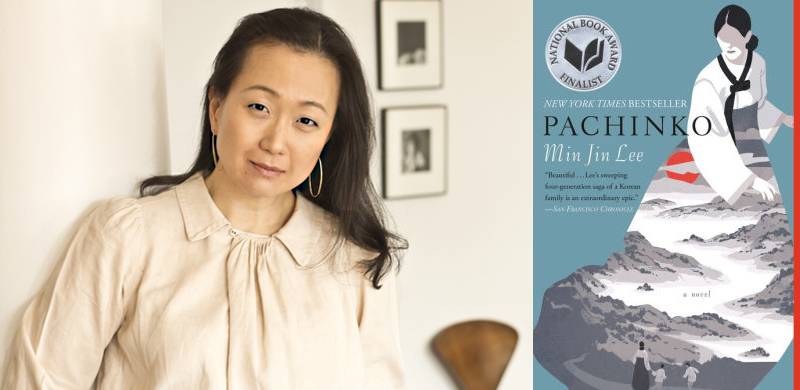

‘History has failed us, but no matter.’ As the opening line for a long story it sets the tone quite accurately. In spite of the myriad of challenges the characters face in this multigenerational novel, the accepted reality that one must plod on makes one empathise with the characters at different points. What’s refreshing is that this realistically fictional tale is told from a Korean-American perspective. ‘Pachinko’ feels very much a labour of love by Min Jin Lee. Undoubtedly, much in-depth research has gone into telling the story of a poor Korean family through four generations, beginning in Korea and then in Japan.

The story weaves a tapestry of real life themes that are relevant to us today: war, identity, immigration, adaptation, racism, nature vs. nurture, gender and stereotypes. At the start of the novel we are introduced to Hoonie, a poor fisherman, “who was born with a cleft palate and a twisted foot.” Decisions made by the landed elites were out of hands of the poor. “Hoonie used to listen carefully to all the men who brought him news, and he would nod, exhale resolutely, and then get up to take care of the chores. The weeds would still have to be pulled from the vegetable garden, rope sandals would need to be woven if they were to have shoes.” Lee gives an apt description of how life has to go on mechanically to get things done.

Similarly, the title ‘Pachinko’ refers to the pinball machine game where the player loads a steel ball into the machine, presses and releases a steel handle, to launch the ball into a metal track. Like the pinball game, the lives of poor Koreans first in their homeland then as immigrants in Japan under Japanese rule, were pretty much out of their hands. However, luck and skill also played a part in outcomes. ‘Man, life’s going to keep pushing you around, but you have to keep pushing.’

At the heart of this expansive story is Sunja. She is the product of loving parents Hoonie and Yangjin. ‘Sunja was not ugly, but not attractive in any obvious way’ but her parents instilled her with self-confidence and pragmatism. Then one day, Sunja had to make a choice that would have far reaching consequences for her life and future generations. All the characters in the 528 pages are linked with Sunja either directly, through marriage, or intimately. She is not a conventionally attractive protagonist with delicate features, yet attractive and self-assured in her person. We see her pragmatic and adaptive skills coming into play to help her survive and make a life for herself and her children.

‘Pachinko Parlors’ were a means to an end as there were very few jobs open to Korean immigrants and their children, who were born in Japan but still had to register as foreigners. Working at Pachinko Parlors does not bring social mobility, and some Koreans like in Noa’s case, hiding one’s identity and not being found out, becomes a way of life. ‘Pachinko gave off an odour of poverty and criminality.’ On the other hand, his brother Mozasu accepts who he is and decides to deal with his identity more openly with different consequences.

‘At least they were together. At least they could work towards something better.’ In contrast to the harsh reality, relationships are imbued with kindness and empathy. Lee shows through her character that traits like kindness and empathy are recipes for humanity and survival rather than weakness and failure. Sisters-in-law have respect for each other; brothers support one another, and husband and wife are loving.

There is a gender aspect to the story that is heartening. Sunja and Kyunghee’s relationship is more like sisters than sisters-in-law. Yangjin, Sunja and Etsuko belong to different generations and have personalities that leave a distinct impression. Sunja’s character is the most nuanced.

Some stereotypes are done away with and addressed differently. Hoonie’s affection for his daughter is not typical of the culture: ‘No one should expect praise, and certainly not a woman, but as a little girl, she’d been treasured, nothing less.’ Isak, a Christian minister, does not expect Sunja to repay him back for his kind deed, but that she come to love him gradually. ‘Isak had not wanted Sunja to turn to God in this way. Love for God, he’d thought, should come naturally, and not out of punishment.’

You often have to give people opportunities to rise to the occasion. I found Koh Hansu to be an intriguing character. He is a ‘yakazu’ (Japanese organized crime member) and adopts Japan as his homeland. A seemingly self-centred personality, Hansu is not so much heartless as he is pragmatic. “If the Korean nationalists couldn’t get their country back, then let your kids learn Japanese and get ahead. Adapt.”

Pachinko for me did not hold too many surprises. Having lived in Japan as a child I was familiar with the history of prejudice towards Koreans. Yet because it is told from a Korean-American writer’s perspective the story is an eye-opener.

For example, Koreans who were born and lived in Japan still had to register as foreigners when they knew no other country but Japan as their home. This is a novel that should be read by those who want an insight into the Korean history and experience. It need not have been so long and the last 100 pages are particularly laborious. At the heart of it, Pachinko shows how significant acts of kindness and cruelty shape lives through multiple generations.

The story weaves a tapestry of real life themes that are relevant to us today: war, identity, immigration, adaptation, racism, nature vs. nurture, gender and stereotypes. At the start of the novel we are introduced to Hoonie, a poor fisherman, “who was born with a cleft palate and a twisted foot.” Decisions made by the landed elites were out of hands of the poor. “Hoonie used to listen carefully to all the men who brought him news, and he would nod, exhale resolutely, and then get up to take care of the chores. The weeds would still have to be pulled from the vegetable garden, rope sandals would need to be woven if they were to have shoes.” Lee gives an apt description of how life has to go on mechanically to get things done.

Similarly, the title ‘Pachinko’ refers to the pinball machine game where the player loads a steel ball into the machine, presses and releases a steel handle, to launch the ball into a metal track. Like the pinball game, the lives of poor Koreans first in their homeland then as immigrants in Japan under Japanese rule, were pretty much out of their hands. However, luck and skill also played a part in outcomes. ‘Man, life’s going to keep pushing you around, but you have to keep pushing.’

At the heart of this expansive story is Sunja. She is the product of loving parents Hoonie and Yangjin. ‘Sunja was not ugly, but not attractive in any obvious way’ but her parents instilled her with self-confidence and pragmatism. Then one day, Sunja had to make a choice that would have far reaching consequences for her life and future generations. All the characters in the 528 pages are linked with Sunja either directly, through marriage, or intimately. She is not a conventionally attractive protagonist with delicate features, yet attractive and self-assured in her person. We see her pragmatic and adaptive skills coming into play to help her survive and make a life for herself and her children.

‘Pachinko Parlors’ were a means to an end as there were very few jobs open to Korean immigrants and their children, who were born in Japan but still had to register as foreigners. Working at Pachinko Parlors does not bring social mobility, and some Koreans like in Noa’s case, hiding one’s identity and not being found out, becomes a way of life. ‘Pachinko gave off an odour of poverty and criminality.’ On the other hand, his brother Mozasu accepts who he is and decides to deal with his identity more openly with different consequences.

‘At least they were together. At least they could work towards something better.’ In contrast to the harsh reality, relationships are imbued with kindness and empathy. Lee shows through her character that traits like kindness and empathy are recipes for humanity and survival rather than weakness and failure. Sisters-in-law have respect for each other; brothers support one another, and husband and wife are loving.

There is a gender aspect to the story that is heartening. Sunja and Kyunghee’s relationship is more like sisters than sisters-in-law. Yangjin, Sunja and Etsuko belong to different generations and have personalities that leave a distinct impression. Sunja’s character is the most nuanced.

Some stereotypes are done away with and addressed differently. Hoonie’s affection for his daughter is not typical of the culture: ‘No one should expect praise, and certainly not a woman, but as a little girl, she’d been treasured, nothing less.’ Isak, a Christian minister, does not expect Sunja to repay him back for his kind deed, but that she come to love him gradually. ‘Isak had not wanted Sunja to turn to God in this way. Love for God, he’d thought, should come naturally, and not out of punishment.’

You often have to give people opportunities to rise to the occasion. I found Koh Hansu to be an intriguing character. He is a ‘yakazu’ (Japanese organized crime member) and adopts Japan as his homeland. A seemingly self-centred personality, Hansu is not so much heartless as he is pragmatic. “If the Korean nationalists couldn’t get their country back, then let your kids learn Japanese and get ahead. Adapt.”

Pachinko for me did not hold too many surprises. Having lived in Japan as a child I was familiar with the history of prejudice towards Koreans. Yet because it is told from a Korean-American writer’s perspective the story is an eye-opener.

For example, Koreans who were born and lived in Japan still had to register as foreigners when they knew no other country but Japan as their home. This is a novel that should be read by those who want an insight into the Korean history and experience. It need not have been so long and the last 100 pages are particularly laborious. At the heart of it, Pachinko shows how significant acts of kindness and cruelty shape lives through multiple generations.