The Prime Minister surprised more than one person by saying that the military had agreed to voluntarily reduce defense spending to reduce the budget deficit. Imran added that reduced defense spending would be used to fund the development of Balochistan.

The military is to be commended for saying the unthinkable. In Pakistan, the assertion that national security is synonymous with military spending has been regarded as gospel for decades. Those holding this view should read Sir Michael Howard’s seminal article, The Forgotten Dimensions of Strategy, Foreign Affairs, 1979.

Sir Michael, who has been described as Britain’s greatest living historian, propounded that national security is not unidimensional. Besides having a strong military, a nation needs to have strong political leadership, social cohesion, economic vitality, and strong foreign policy. I quoted him in my 2003 book on Pakistan’s national security. A decade later, this dictum was echoed by the Abbottabad Commission.

Pakistan’s conventional forces are out-numbered 2:1 by India’s. Can Pakistan afford to live with a higher ratio given that it has an edge over Indian in its nuclear arsenal?

Let’s take a quick look at history. The ratio between Indian and Pakistani forces has hovered at 2:1 for the past two decades. It was 4.2 in 1965. In 1971, it dropped to 2.5:1. Of course, in East Pakistan the ratio was much worse. The Pakistani forces were worn out after months of fighting a tenacious insurgency and the troops from West Pakistan had been flown there without their full complement of armor or artillery. They were totally without air cover once the Indian Air Force put the Dacca runway out of commission.

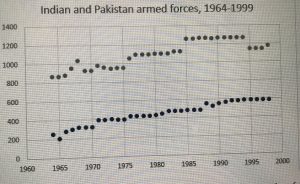

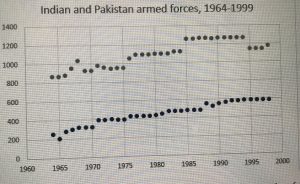

The chart below shows Indian (larger) and Pakistani (smaller) forces from 1964 to 1999, measured in thousands of armed personnel.

After 1971, Pakistan lost half of its population. So the ratio of forces should have become larger. Instead, it got smaller reflecting Pakistan’s misplaced sense of insecurity.

Writing in the authoritative journal, “International Security” in 1989, Mearsheimer stated that between forces of comparable quality and firepower, the ratio between the attacker’s forces and the defender’s forces will have to be 3:1 or higher to ensure a breakthrough.

Conversely, if the ratio is much lower, say 2:1, the attacker cannot be assured of victory. History will not be on his side unless one or more of the following conditions are fulfilled: his troops are better trained, they have better armor, artillery, air and naval support, and they are able to pull off a surprise attack.

Why does the attacker need a superior force than the defender? First, the defender is more likely to inflict a greater number of casualties on the attacker than vice versa. Thus, he needs to only have a third of the strength of the attacker.

Second, the defender is almost certainly going to have better knowledge of the terrain in his country. Third, he will be fighting from known positions where he can conceal his whereabouts and fire at the enemy more accurately. Fourth, his supply lines will be shorter. Fifth, he will be able to create ditches, lay out mines and traps designed to steer the attacker into a killing zone. And, sixth, his civilian population is likely to be on his side (unless there is an active insurgency, as was the case in East Pakistan).

If the ratio is lower, the attacker will be hit with a higher number of casualties faster than the defender. His forces are likely to lose their unity and discipline and crumble, ceasing to be a fighting force.

The 3:1 value is derived from a study of military history. The Rule of 3 to 1 is not just an academic idea. It’s used by militaries throughout the globe.

For example, it’s cited in the US Army’s Field Manual 100, which derives it from a meticulous review of historical battles, wartime diaries, peacetime exercises and war games. Mearsheimer notes that during the height of the Cold War, the Soviet army sought a ratio of 5:1 in personnel, 9:1 in artillery and 3:1 in tanks.

Mearsheimer says the 3:1 rule is a powerful predictor of battlefield outcomes. Thus, most commanding officers subscribe to it and so do most army doctrines.

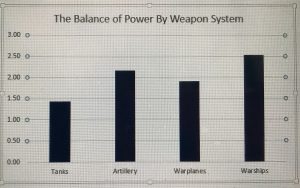

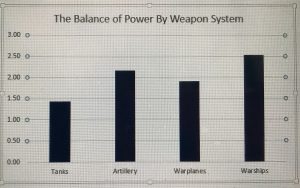

Despite the attainment of parity in nuclear weapons, and the induction of a wide assortment of delivery systems, the ratio of conventional forces between India and Pakistan has not budged from its 2:1 value. There has been no nuclear dividend. Here are the ratios by major weapon systems. None are 3:1 or higher.

Given all this evidence about the current ratios of armed forces and major weapon systems, India cannot mount a successful attack on Pakistan. Thus, Pakistan can raise the 2:1 ratio to 3:1 without compromising its national security. Indeed, it may even get by with a higher ratio for three reasons. First, it has reached nuclear parity with India. Second, India also has to contend with China and cannot deploy all its forces against Pakistan. And, third, according to a number of experts, Indian weaponry is aging and not well maintained.

With a conservative3:1 ratio, the strength of the Pakistani armed forces would be reduced from 600,000 to 400,000, approximately the number it had during the 1971 war. Personnel costs would go down proportionately.

Some reduction would also be expected in the arsenal of weapons, allowing Pakistan to reduce its defense budget by 20-25%. The freed-up money can be spent on development, as indicated by the Prime Minister.

Such a change in the defense budget will not compromise national security. Indeed, it would raise it. Why? Because the money saved could be spent on cultural, social and economic development. Anyone doubting this policy should study the collapse of the USSR in 1991, which was bankrupted by overspending on defense.

Of course, certain well-intentioned patriots, and Pakistan has more than few, will argue that Pakistan is surrounded by enemies.

The list includes not just India on the eastern border, but also Afghanistan, possibly Iran, maybe Israel and perhaps even the United States, an erstwhile ally. They will assert that these enemies are waging a hybrid war against Pakistan, that they have penetrated its porous boundaries, and that they are now operating freely inside the country.

These concerns reflect a deep-rooted paranoia in national security policy formulation in Pakistan. How could a nation, any nation, have so many enemies?

And if that is indeed true, Pakistan does not have a military problem. It has a major foreign policy problem.

The military is to be commended for saying the unthinkable. In Pakistan, the assertion that national security is synonymous with military spending has been regarded as gospel for decades. Those holding this view should read Sir Michael Howard’s seminal article, The Forgotten Dimensions of Strategy, Foreign Affairs, 1979.

Sir Michael, who has been described as Britain’s greatest living historian, propounded that national security is not unidimensional. Besides having a strong military, a nation needs to have strong political leadership, social cohesion, economic vitality, and strong foreign policy. I quoted him in my 2003 book on Pakistan’s national security. A decade later, this dictum was echoed by the Abbottabad Commission.

Pakistan’s conventional forces are out-numbered 2:1 by India’s. Can Pakistan afford to live with a higher ratio given that it has an edge over Indian in its nuclear arsenal?

Let’s take a quick look at history. The ratio between Indian and Pakistani forces has hovered at 2:1 for the past two decades. It was 4.2 in 1965. In 1971, it dropped to 2.5:1. Of course, in East Pakistan the ratio was much worse. The Pakistani forces were worn out after months of fighting a tenacious insurgency and the troops from West Pakistan had been flown there without their full complement of armor or artillery. They were totally without air cover once the Indian Air Force put the Dacca runway out of commission.

The chart below shows Indian (larger) and Pakistani (smaller) forces from 1964 to 1999, measured in thousands of armed personnel.

After 1971, Pakistan lost half of its population. So the ratio of forces should have become larger. Instead, it got smaller reflecting Pakistan’s misplaced sense of insecurity.

Writing in the authoritative journal, “International Security” in 1989, Mearsheimer stated that between forces of comparable quality and firepower, the ratio between the attacker’s forces and the defender’s forces will have to be 3:1 or higher to ensure a breakthrough.

Conversely, if the ratio is much lower, say 2:1, the attacker cannot be assured of victory. History will not be on his side unless one or more of the following conditions are fulfilled: his troops are better trained, they have better armor, artillery, air and naval support, and they are able to pull off a surprise attack.

Why does the attacker need a superior force than the defender? First, the defender is more likely to inflict a greater number of casualties on the attacker than vice versa. Thus, he needs to only have a third of the strength of the attacker.

Second, the defender is almost certainly going to have better knowledge of the terrain in his country. Third, he will be fighting from known positions where he can conceal his whereabouts and fire at the enemy more accurately. Fourth, his supply lines will be shorter. Fifth, he will be able to create ditches, lay out mines and traps designed to steer the attacker into a killing zone. And, sixth, his civilian population is likely to be on his side (unless there is an active insurgency, as was the case in East Pakistan).

If the ratio is lower, the attacker will be hit with a higher number of casualties faster than the defender. His forces are likely to lose their unity and discipline and crumble, ceasing to be a fighting force.

The 3:1 value is derived from a study of military history. The Rule of 3 to 1 is not just an academic idea. It’s used by militaries throughout the globe.

For example, it’s cited in the US Army’s Field Manual 100, which derives it from a meticulous review of historical battles, wartime diaries, peacetime exercises and war games. Mearsheimer notes that during the height of the Cold War, the Soviet army sought a ratio of 5:1 in personnel, 9:1 in artillery and 3:1 in tanks.

Mearsheimer says the 3:1 rule is a powerful predictor of battlefield outcomes. Thus, most commanding officers subscribe to it and so do most army doctrines.

Despite the attainment of parity in nuclear weapons, and the induction of a wide assortment of delivery systems, the ratio of conventional forces between India and Pakistan has not budged from its 2:1 value. There has been no nuclear dividend. Here are the ratios by major weapon systems. None are 3:1 or higher.

Given all this evidence about the current ratios of armed forces and major weapon systems, India cannot mount a successful attack on Pakistan. Thus, Pakistan can raise the 2:1 ratio to 3:1 without compromising its national security. Indeed, it may even get by with a higher ratio for three reasons. First, it has reached nuclear parity with India. Second, India also has to contend with China and cannot deploy all its forces against Pakistan. And, third, according to a number of experts, Indian weaponry is aging and not well maintained.

With a conservative3:1 ratio, the strength of the Pakistani armed forces would be reduced from 600,000 to 400,000, approximately the number it had during the 1971 war. Personnel costs would go down proportionately.

Some reduction would also be expected in the arsenal of weapons, allowing Pakistan to reduce its defense budget by 20-25%. The freed-up money can be spent on development, as indicated by the Prime Minister.

Such a change in the defense budget will not compromise national security. Indeed, it would raise it. Why? Because the money saved could be spent on cultural, social and economic development. Anyone doubting this policy should study the collapse of the USSR in 1991, which was bankrupted by overspending on defense.

Of course, certain well-intentioned patriots, and Pakistan has more than few, will argue that Pakistan is surrounded by enemies.

The list includes not just India on the eastern border, but also Afghanistan, possibly Iran, maybe Israel and perhaps even the United States, an erstwhile ally. They will assert that these enemies are waging a hybrid war against Pakistan, that they have penetrated its porous boundaries, and that they are now operating freely inside the country.

These concerns reflect a deep-rooted paranoia in national security policy formulation in Pakistan. How could a nation, any nation, have so many enemies?

And if that is indeed true, Pakistan does not have a military problem. It has a major foreign policy problem.