Kargil has captivated the minds of political and military thinkers in Pakistan for two decades now. The catastrophic military debacle that led to the overthrow of Nawaz Sharif's second government in October 1999 is also important for its political ramifications. Ahmad Faruqui in this article lays out the ten critical findings from Nasim Zehra's book 'From Kargil to the Coup', released in 2018.

In the spring of 1999, the Pakistani army under General Pervez Musharraf carried out a covert operation against Indian positions in Kargil, triggering a strong Indian counteroffensive. The prime minister traveled to Washington in July to discuss the Kashmir issue. The Indians refused to show up saying they would not accept US mediation. The US called on Pakistan to pull back from the brink and Pakistan agreed. The only concession to Pakistan was a statement by the American president that he would take a “personal interest” in Kashmir. Totally humiliated, the army overthrew the elected government in October.

This debacle has been the subject of much scholarly debate. A great collection of essays appears in the book edited by Peter Lavoy. What was missing in the debate was research based on primary interviews. Nasim Zehra has filled that gap.

The Kargil operation confirmed that Pakistan’s grand strategy is India-centric, and that it wants to wrest Kashmir from India at all costs. When a proxy war carried out over many years failed to instigate an uprising, a military operation was carried out. What made the Kargil operation different was that Pakistan showed a willingness to risk a nuclear war to gain Kashmir. The strategy was to disguise the infantry operation as if it was an indigenous uprising. It was assumed that the element of surprise, coupled with the better training and armaments of the army battalions, would ensure a quick win.

Ten major findings emerge from Zehra’s narration of the main events.

First, Operation KP (Koh Paima) began in October 1998, when Musharraf took over as army chief. He believed that the only way to resolve the festering Kashmir dispute was through force. He also felt that now was the time to act before India became too big for Pakistan. In August 1965, when India was not quite so big in a relative sense, Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had said the same thing to Field Marshal Ayub, precipitating Operation Gibraltar and then Operation Grand Slam in Indian Kashmir which resulted in India attacking Lahore on the 6th of September.

Second, KP was planned in complete secrecy. Maj-Gen Javed Hassan, KP’s commander, considered himself a geopolitical strategist. He assumed that the nuclear shield would guarantee military and diplomatic success in Kargil since India would not up the ante.

Third, KP would cut off India’s lifeline to its troops in Leh, NH1, resulting in its withdrawal from Siachen. Furthermore, Musharraf, a professed disciple of Napoleon’s, believed that luck favoured the brave.

Fourth, KP did not include a defence plan and was mounted without artillery and logistical support. The going-in assumptions were that, first, Pakistan’s posts were impregnable; second, Indians would not fight back; and third, there would be no international pressure on Pakistan. All three assumptions would be proven wrong.

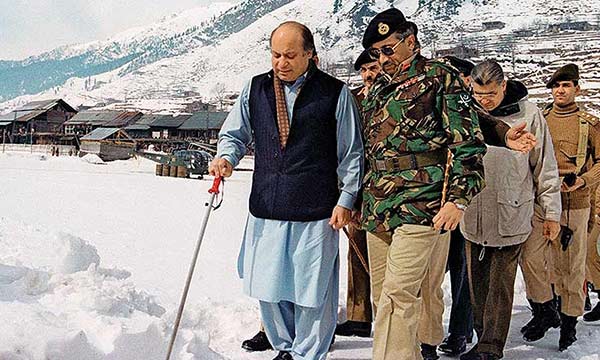

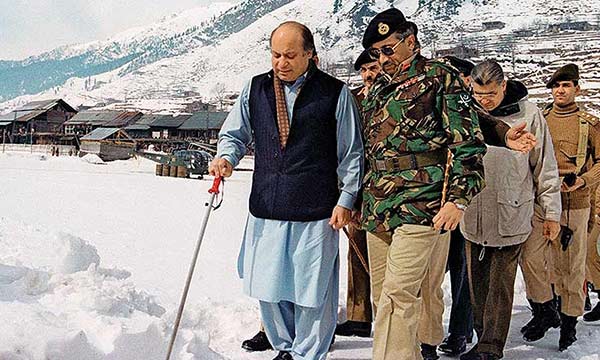

Fifth, as the operation progressed, Musharraf flew with the prime minister to the battlements near Kargil and showed him the plan. His Chief of the General Staff told Nawaz that he was about to enter the history books as the only PM who had solved the Kashmir imbroglio. Later, another officer told Nawaz that he would rank only second to Jinnah in Pakistani history.

Sixth, late in the game, the air and naval chiefs were brought into confidence. Perplexed, both asked “What would be achieved?” They were also concerned that KP would lead to an all-out war with India. They were told that war with India was unlikely, courtesy of the nuclear shield. Instead, KP would force India to the negotiating table. One general said there was no choice but to fight India since our animosity was eternal.

Seventh, the euphoria ended in May 1999 when India detected the intrusion. It responded with an intense and sustained artillery barrage with 30-kilometer Bofors guns. A total of 250,000 shells, bombs and rockets were fired at Pakistani positions in a three-week period. Pakistan was forced to deploy its artillery. But it ran out of shells in just two days, not the two months that they were supposed to last. The operations commander lost his nerve and began to ask for God’s forgiveness, admitted that he had made a mistake, and asked everyone to pray. Around that time, India released the transcript of a phone conversation between Musharraf and his CGS which shattered Musharraf’s contention that Pakistan was not involved in the operation.

Eight, it was all downhill from there. The world came down hard on Pakistan. The G-8 called on Pakistan to withdraw unconditionally as did the US and the ‘all-weather friend’ China. France forbade Pakistani submarines, most of which were of French origin, from entering French waters. And India turned off the back-channel diplomacy with Pakistan. Of course, that was expected. But world condemnation had not been anticipated.

Nine, the GHQ’s spin-doctors got to work immediately, hoping to convince the gullible public that the politicians had squandered the military’s hard-won victory. A frustrated Musharraf, showing scant regard for the constitution, seized power a year after he had launched KP. In his maiden speech, he told the nation that “your armed forces have never let you down.” Within days, he was bragging to an English reporter: “It’s a good feeling to be in charge.”

Tenth, the army had once again proven Air Marshal Asghar Khan’s dictum, that Pakistan never learned anything from history.

Zehra’s book makes it amply clear that KP was criticised by several generals. Maj-Gen Shahid Aziz said it was an “unsound military plan based on invalid assumptions, launched with little preparation and in total disregard to the regional and international environment, was bound to fail.” Lt-Gen Durrani said that the Kargil incursion had “brought home the realities of international politics” and exposed the dangers of getting carried away by “self-serving hopes and hypes.” Lt-Gen Gulzar called KP a “blunder of Himalayan proportions.” Lt-Gen Ali Quli termed the attack on Kargil “the worst debacle in Pakistan’s history.”

Undeterred, in search for greater glory, the army had marched into Kargil. When General Musharraf’s luck ran out on the battlefield, he mounted a coup.

In the spring of 1999, the Pakistani army under General Pervez Musharraf carried out a covert operation against Indian positions in Kargil, triggering a strong Indian counteroffensive. The prime minister traveled to Washington in July to discuss the Kashmir issue. The Indians refused to show up saying they would not accept US mediation. The US called on Pakistan to pull back from the brink and Pakistan agreed. The only concession to Pakistan was a statement by the American president that he would take a “personal interest” in Kashmir. Totally humiliated, the army overthrew the elected government in October.

This debacle has been the subject of much scholarly debate. A great collection of essays appears in the book edited by Peter Lavoy. What was missing in the debate was research based on primary interviews. Nasim Zehra has filled that gap.

The Kargil operation confirmed that Pakistan’s grand strategy is India-centric, and that it wants to wrest Kashmir from India at all costs. When a proxy war carried out over many years failed to instigate an uprising, a military operation was carried out. What made the Kargil operation different was that Pakistan showed a willingness to risk a nuclear war to gain Kashmir. The strategy was to disguise the infantry operation as if it was an indigenous uprising. It was assumed that the element of surprise, coupled with the better training and armaments of the army battalions, would ensure a quick win.

Ten major findings emerge from Zehra’s narration of the main events.

First, Operation KP (Koh Paima) began in October 1998, when Musharraf took over as army chief. He believed that the only way to resolve the festering Kashmir dispute was through force. He also felt that now was the time to act before India became too big for Pakistan. In August 1965, when India was not quite so big in a relative sense, Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had said the same thing to Field Marshal Ayub, precipitating Operation Gibraltar and then Operation Grand Slam in Indian Kashmir which resulted in India attacking Lahore on the 6th of September.

Second, KP was planned in complete secrecy. Maj-Gen Javed Hassan, KP’s commander, considered himself a geopolitical strategist. He assumed that the nuclear shield would guarantee military and diplomatic success in Kargil since India would not up the ante.

Third, KP would cut off India’s lifeline to its troops in Leh, NH1, resulting in its withdrawal from Siachen. Furthermore, Musharraf, a professed disciple of Napoleon’s, believed that luck favoured the brave.

Fourth, KP did not include a defence plan and was mounted without artillery and logistical support. The going-in assumptions were that, first, Pakistan’s posts were impregnable; second, Indians would not fight back; and third, there would be no international pressure on Pakistan. All three assumptions would be proven wrong.

Fifth, as the operation progressed, Musharraf flew with the prime minister to the battlements near Kargil and showed him the plan. His Chief of the General Staff told Nawaz that he was about to enter the history books as the only PM who had solved the Kashmir imbroglio. Later, another officer told Nawaz that he would rank only second to Jinnah in Pakistani history.

Sixth, late in the game, the air and naval chiefs were brought into confidence. Perplexed, both asked “What would be achieved?” They were also concerned that KP would lead to an all-out war with India. They were told that war with India was unlikely, courtesy of the nuclear shield. Instead, KP would force India to the negotiating table. One general said there was no choice but to fight India since our animosity was eternal.

Seventh, the euphoria ended in May 1999 when India detected the intrusion. It responded with an intense and sustained artillery barrage with 30-kilometer Bofors guns. A total of 250,000 shells, bombs and rockets were fired at Pakistani positions in a three-week period. Pakistan was forced to deploy its artillery. But it ran out of shells in just two days, not the two months that they were supposed to last. The operations commander lost his nerve and began to ask for God’s forgiveness, admitted that he had made a mistake, and asked everyone to pray. Around that time, India released the transcript of a phone conversation between Musharraf and his CGS which shattered Musharraf’s contention that Pakistan was not involved in the operation.

Eight, it was all downhill from there. The world came down hard on Pakistan. The G-8 called on Pakistan to withdraw unconditionally as did the US and the ‘all-weather friend’ China. France forbade Pakistani submarines, most of which were of French origin, from entering French waters. And India turned off the back-channel diplomacy with Pakistan. Of course, that was expected. But world condemnation had not been anticipated.

Nine, the GHQ’s spin-doctors got to work immediately, hoping to convince the gullible public that the politicians had squandered the military’s hard-won victory. A frustrated Musharraf, showing scant regard for the constitution, seized power a year after he had launched KP. In his maiden speech, he told the nation that “your armed forces have never let you down.” Within days, he was bragging to an English reporter: “It’s a good feeling to be in charge.”

Tenth, the army had once again proven Air Marshal Asghar Khan’s dictum, that Pakistan never learned anything from history.

Zehra’s book makes it amply clear that KP was criticised by several generals. Maj-Gen Shahid Aziz said it was an “unsound military plan based on invalid assumptions, launched with little preparation and in total disregard to the regional and international environment, was bound to fail.” Lt-Gen Durrani said that the Kargil incursion had “brought home the realities of international politics” and exposed the dangers of getting carried away by “self-serving hopes and hypes.” Lt-Gen Gulzar called KP a “blunder of Himalayan proportions.” Lt-Gen Ali Quli termed the attack on Kargil “the worst debacle in Pakistan’s history.”

Undeterred, in search for greater glory, the army had marched into Kargil. When General Musharraf’s luck ran out on the battlefield, he mounted a coup.