There have never been as many media outlets and forms of media in India or Pakistan as there are today -- or as much push for freedom of expression and information, and its counterpoint, various forms of censorship.

The addition of digital and web initiatives to the traditional print and broadcast media landscape, and rise of social media platforms, has added to the complexity of the picture. Today, growing numbers of social media users exercise increasing influence on all forms of media and public discourse in South Asia.

The English-language media, with its global reach, has generally upheld more progressive values, while local-language media tended to be more reactionary. However, these generalizations do not accurately reflect the entire picture now.

One reason the English language media in Pakistan has in the past been allowed a relatively free rein is its value as window dressing. Allowing a certain amount of freedom to this media shows the world how much press freedom Pakistan has.

But in recent years, the English-language media has become the site of the war of narratives particularly online, with organized efforts behind dozens of ‘news and analysis’ websites. About 25 dubious websites related to Pakistan current affairs use the same font for their logos and masthead, says a journalist who runs his own independent news website. These websites list no contact details or any credible names in their editorial staff. In March 2019, Facebook removed hundreds of pages from India and Pakistan that exhibited “coordinated inauthentic behaviour and spam”.

The narrative peddled in these dubious websites is echoed in hundreds if not thousands of Facebook pages and Twitter accounts, that engage also in trolling and abusing progressive journalists and analysts. In March 2019, Facebook removed hundreds of pages from India and Pakistan that exhibited “coordinated inauthentic behaviour and spam” including groups and accounts linked to employees of the Pakistani military’s public relations arm. In early April, 2019, Facebook’s largest purge in India axed around 200 pro-BJP pages.

Polarization within and between various forms of media reflect the cleavages within society as well as across borders. The online chatter does not always reflect reality even as it dominates the narrative.

Missing from the mainstream

Journalists have long been aware of the main no-go areas for mainstream media in Pakistan. These include national security and religion. Over the past years, a certain level of critical analysis had increasingly crept into mainstream as well as social media. The backlash from those who control the narrative has been severe. There are red lines which may not be crossed. These lines keep changing.

A case in point is the near total media blackout of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM, or the Movement for the Protection of Pashtuns) that developed from protests against the extrajudicial murder of a Pashtun youth, Naqeebullah Mehsud, in Karachi in January 2018. He and his family were among the 1.5 million Pakistanis internally displaced by military operations against militants in Pakistan’s north-west since 2004.

Had it not been for social media, Naqeebullah Mehsud’s death may well have been just another of the over 3,000 such targeted killings of suspected militants by security forces around the country since 2015. Rights activists have been calling for transparency and accountability around these deaths, but security forces have not allowed any independent verification, including by journalists.

When Naqeebullah Mehsud’s friends and followers took to social media in outrage against his murder, it became quickly obvious that the youth was an aspiring model and actor, not a militant.

The injustice sparked a movement that has drawn hundreds of thousands at peaceful demonstrations throughout the year around the country. Protestors, many with smartphones in their hands, are demanding an end to the racial profiling and extrajudicial killings of Pashtuns, stereotyped as ‘Taliban’. The large presence of women at these demonstrations has also broken social taboos against gender segregation.

The PTM’s demands for constitutional rights directly challenge Pakistan’s powerful security establishment. But they have been consistently blocked from the mainstream media. In contrast, in the run up to general elections in July 2018, former cricket hero-turned politician Imran Khan, widely seen as an establishment favourite, got hours of advertisement-free coverage for his electoral rallies and speeches. PTM’s demands for constitutional rights directly challenging Pakistan’s powerful security establishment have been.

Journalists, blocked from reporting on these matters in their media outlets, took to social media to share information. Without social media, “the movement would not be possible,” acknowledged the PTM leaders.

The rapid rise of social media in Pakistan (with 17 per cent internet penetration, growing fast) and mobile phone subscribers (over 70 per cent) makes television coverage (73 per cent) less crucial than before. Censorship violates the people’s right to know, as a statement endorsed by over 100 journalists in April 2018 stressed.

“Beginning with a crackdown against select media groups and banning the broadcast of various channels, there now is enhanced pressure on all media houses to refrain from covering certain rights-based movements. Media house managements under pressure are dropping regular op-ed columns and removing online editions of published articles. One media house even asked its anchors to stop live shows. There is growing self-censorship and increasingly, discussions on 'given news' rather than real news, violating the citizens’ right to information,” said the statement.

The case of the small but fast-growing digital platform Naya Daur (New Age) illustrated the clampdown on narratives other than the ‘approved’ one, and the obfuscation of whatever entity or entities are behind the censorship.

When daily The Nation dropped weekly columnist Gul Bukhari's op-ed about PTM she sent it to Naya Daur’s editor, Raza Rumi who has been based in the USA since escaping a murderous attempt in 2014. Naya Daur, which was also sharing other PTM-related material, posted Bukhari’s piece on April 16, 2018. The website was subsequently blocked in Pakistan for a week (April 21-28, 2018). The Pakistan Telecom Authority as well as the country’s largest internet provider, the semi-private Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited, denied responsibility. Mobile phone users subscribing to the service provider Wateen, as well as Chinese provider Zong, could also not access the Naya Daur website.

Even after two of PTM’s leaders were elected to Parliament, organized campaigns on social media and television continued to vilify the movement’s leaders and supporters as “traitors” and “foreign agents” – a common tool against anyone countering the establishment narrative. Attempts to derail PTM’s demonstrations included police picking up activists and confiscating pamphlets in Lahore and Karachi. Each time, social media reactions contributed to the activists being released.

Narrative-controlling attempts are also visible at educational institutions. In April 2018, an open letter signed by nearly 300 academics listed four “separate but related instances of repression” at campuses in various cities between April 12 and April 13, 2018, termed as “part of a wider trend that stifles critical thinking and discussion on university campuses”.

The result is an overall stifling of dissent and restriction of spaces for free expression.

War-mongering post-Pulwama

Lack of transparency around security issues and selective broadcast of news related to such issues allows only certain narratives to reach the public. The 24/7 media beast and social media users tend to cherry pick the most sensational and outrageous comments and hype them up. This has dire consequences for peace and democracy in South Asia, particularly between India and Pakistan.

The Indian mainstream media is largely filled with war-mongering, frothing-at-the-mouth television anchors and screaming headlines based on political statements supporting a hate-filled rhetoric. This gives the impression that the entire country supports these views. Such elements are visible in the Pakistani media too, but the commentary has on the whole been far more temperate for some time now.

The violent narrative that overwhelms public discourse leaves little space for reasonable voices or any nuance or positivity. Yet many on the ground engaged in work that generates positivity continue to do that work, for example in the areas of health, education, peace-building and empowerment of marginalized communities. Their efforts rarely make the news.

The suicide attack on a military convoy in Pulwama in the Indian-administered Kashmir in February 2019 marked a low point in media coverage of the fraught relations between India and Pakistan. Post-Pulwama, public narratives in India and Pakistan were exceedingly polarized. Newspapers, TV channels, websites and social media timelines were filled with glorifying and justifying actions of the “home team” as it were. Those attempting to question these narratives are subjected to a barrage of abuse and accusations of being ‘traitor’.

The lack of transparency on both sides of the border makes it difficult to know what really happened in a conflict situation. When soldiers or civilians are injured or killed in ceasefire violations at the Line of Control in the disputed region of Kashmir, the governments and media of both Pakistan and India only report their own side’s casualties. Both claim “unprovoked” firing from across the border.

The possibilities of peace

Trolls and those pushing fascist, violent agendas have taken to social media in an organised way. Recognising its value, they are using it effectively to push their narratives in the public domain. Many are paid to do this. As they do so, they create space for those who agree with their views to come online and publicly say what was unacceptable before.

These paid armies and their associate volunteers are crowding out the original promise of social media – more space for pluralism, peace, and democracy. But the original dream is also still very much alive, even if those upholding it are not as well-organised or paid.

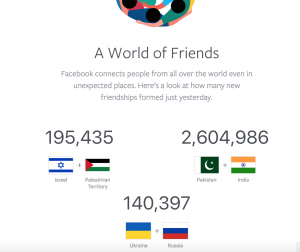

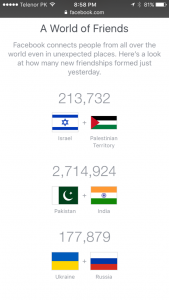

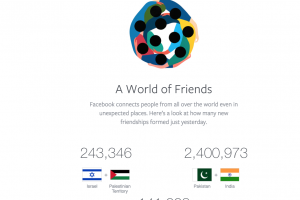

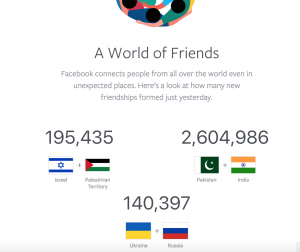

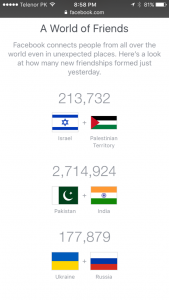

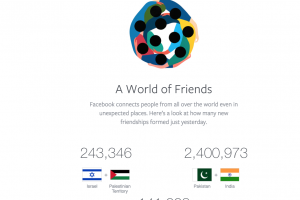

According to Facebook data, 2,604,986 Facebook users from India and Pakistan connected as ‘friends’ on 4 March 2018, from its site, www.fb.com/peace, that provided data on how many people formed friendships daily across three conflict zones. (This the same figure as on 26 December 2017 so perhaps Facebook had stopped updating the numbers before discontinuing the tool). The average for India and Pakistan, going by numbers updated daily, was around 250,000 pretty much any day. This indicates at least a level of curiosity if not aspirations for peace and friendship across borders, that social media platforms provide space for.

An unprecedented – perhaps in the world – example of cross-border media cooperation with a specific agenda for peace building that continues to be a platform for such aspirations is Aman Ki Asha (Hope for Peace). The two large media groups behind it, Jang Group of Pakistan and the Times of India, that launched it on 1 January 2010 may have lost interest in this CSR over the past few years but it continues to be a good example of reporting about a cause - journalism combined with peace activism.

For the first few years, Aman Ki Asha music and literary festivals, economic symposiums and seminars discussing strategic issues, were organised in cities around India and Pakistan. The Jang Group and TOI reported on these events in their newspapers, sometimes as full-page supplements; the Jang Group’s Geo TV also broadcast reports about these events. Often other media, however, chose not to cover such events as most publications then would not name or promote any activity by their professional rivals.

In Pakistan, the Jang Group also published a weekly Aman Ki Asha page in its English and Urdu papers until 2014. The printed pages were dropped due to commercial and other pressures, but the editor continues to curate, commission, and edit material for the website from where it is shared to the Aman Ki Asha social media accounts and beyond.

The platform has since its launch consistently provided a space for “peace mongers” in the region. Young people often message the Facebook page with initiatives and ideas that Aman Ki Asha takes up and works with editorially. The content produced for the website and in the social media platforms helps counter the jingoism and war rhetoric played up by the mainstream media.

On April 3, 2019, when actor Bushra Ansari released a music video based on a peace poem by her older sister Neelum Bashir, Neelum asked a young friend in India (who actually started and manages her other actor sister Asma’s Facebook fan page) to share it with Aman Ki Asha on Facebook. The video was posted to the AKA Facebook Page and Twitter feed, and shared in the AKA group and elsewhere by countless members. The song, performed as a duet between two neighbours separated by an insurmountable wall went viral, forcing the mainstream media to take it up.

The video’s popularity in India and in Pakistan cuts through the political rhetoric against either country. This is just one indication of the people’s aspirations for peace and good relations between the two countries, drowned out by the din of warmongering dominating the airwaves and social media, but still alive and kicking.

[This article is based upon extracts from “Truth vs Misinformation: South Asia Press Freedom Report 2018-19” which can be accessed here https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1VZyAfj_GrbEkdN0pOEaxo1RrZrSgRIOk]

The addition of digital and web initiatives to the traditional print and broadcast media landscape, and rise of social media platforms, has added to the complexity of the picture. Today, growing numbers of social media users exercise increasing influence on all forms of media and public discourse in South Asia.

The English-language media, with its global reach, has generally upheld more progressive values, while local-language media tended to be more reactionary. However, these generalizations do not accurately reflect the entire picture now.

One reason the English language media in Pakistan has in the past been allowed a relatively free rein is its value as window dressing. Allowing a certain amount of freedom to this media shows the world how much press freedom Pakistan has.

But in recent years, the English-language media has become the site of the war of narratives particularly online, with organized efforts behind dozens of ‘news and analysis’ websites. About 25 dubious websites related to Pakistan current affairs use the same font for their logos and masthead, says a journalist who runs his own independent news website. These websites list no contact details or any credible names in their editorial staff. In March 2019, Facebook removed hundreds of pages from India and Pakistan that exhibited “coordinated inauthentic behaviour and spam”.

The narrative peddled in these dubious websites is echoed in hundreds if not thousands of Facebook pages and Twitter accounts, that engage also in trolling and abusing progressive journalists and analysts. In March 2019, Facebook removed hundreds of pages from India and Pakistan that exhibited “coordinated inauthentic behaviour and spam” including groups and accounts linked to employees of the Pakistani military’s public relations arm. In early April, 2019, Facebook’s largest purge in India axed around 200 pro-BJP pages.

Polarization within and between various forms of media reflect the cleavages within society as well as across borders. The online chatter does not always reflect reality even as it dominates the narrative.

Missing from the mainstream

Journalists have long been aware of the main no-go areas for mainstream media in Pakistan. These include national security and religion. Over the past years, a certain level of critical analysis had increasingly crept into mainstream as well as social media. The backlash from those who control the narrative has been severe. There are red lines which may not be crossed. These lines keep changing.

A case in point is the near total media blackout of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM, or the Movement for the Protection of Pashtuns) that developed from protests against the extrajudicial murder of a Pashtun youth, Naqeebullah Mehsud, in Karachi in January 2018. He and his family were among the 1.5 million Pakistanis internally displaced by military operations against militants in Pakistan’s north-west since 2004.

Had it not been for social media, Naqeebullah Mehsud’s death may well have been just another of the over 3,000 such targeted killings of suspected militants by security forces around the country since 2015. Rights activists have been calling for transparency and accountability around these deaths, but security forces have not allowed any independent verification, including by journalists.

When Naqeebullah Mehsud’s friends and followers took to social media in outrage against his murder, it became quickly obvious that the youth was an aspiring model and actor, not a militant.

The injustice sparked a movement that has drawn hundreds of thousands at peaceful demonstrations throughout the year around the country. Protestors, many with smartphones in their hands, are demanding an end to the racial profiling and extrajudicial killings of Pashtuns, stereotyped as ‘Taliban’. The large presence of women at these demonstrations has also broken social taboos against gender segregation.

The PTM’s demands for constitutional rights directly challenge Pakistan’s powerful security establishment. But they have been consistently blocked from the mainstream media. In contrast, in the run up to general elections in July 2018, former cricket hero-turned politician Imran Khan, widely seen as an establishment favourite, got hours of advertisement-free coverage for his electoral rallies and speeches. PTM’s demands for constitutional rights directly challenging Pakistan’s powerful security establishment have been.

Journalists, blocked from reporting on these matters in their media outlets, took to social media to share information. Without social media, “the movement would not be possible,” acknowledged the PTM leaders.

The rapid rise of social media in Pakistan (with 17 per cent internet penetration, growing fast) and mobile phone subscribers (over 70 per cent) makes television coverage (73 per cent) less crucial than before. Censorship violates the people’s right to know, as a statement endorsed by over 100 journalists in April 2018 stressed.

“Beginning with a crackdown against select media groups and banning the broadcast of various channels, there now is enhanced pressure on all media houses to refrain from covering certain rights-based movements. Media house managements under pressure are dropping regular op-ed columns and removing online editions of published articles. One media house even asked its anchors to stop live shows. There is growing self-censorship and increasingly, discussions on 'given news' rather than real news, violating the citizens’ right to information,” said the statement.

The case of the small but fast-growing digital platform Naya Daur (New Age) illustrated the clampdown on narratives other than the ‘approved’ one, and the obfuscation of whatever entity or entities are behind the censorship.

When daily The Nation dropped weekly columnist Gul Bukhari's op-ed about PTM she sent it to Naya Daur’s editor, Raza Rumi who has been based in the USA since escaping a murderous attempt in 2014. Naya Daur, which was also sharing other PTM-related material, posted Bukhari’s piece on April 16, 2018. The website was subsequently blocked in Pakistan for a week (April 21-28, 2018). The Pakistan Telecom Authority as well as the country’s largest internet provider, the semi-private Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited, denied responsibility. Mobile phone users subscribing to the service provider Wateen, as well as Chinese provider Zong, could also not access the Naya Daur website.

Even after two of PTM’s leaders were elected to Parliament, organized campaigns on social media and television continued to vilify the movement’s leaders and supporters as “traitors” and “foreign agents” – a common tool against anyone countering the establishment narrative. Attempts to derail PTM’s demonstrations included police picking up activists and confiscating pamphlets in Lahore and Karachi. Each time, social media reactions contributed to the activists being released.

Narrative-controlling attempts are also visible at educational institutions. In April 2018, an open letter signed by nearly 300 academics listed four “separate but related instances of repression” at campuses in various cities between April 12 and April 13, 2018, termed as “part of a wider trend that stifles critical thinking and discussion on university campuses”.

The result is an overall stifling of dissent and restriction of spaces for free expression.

War-mongering post-Pulwama

Lack of transparency around security issues and selective broadcast of news related to such issues allows only certain narratives to reach the public. The 24/7 media beast and social media users tend to cherry pick the most sensational and outrageous comments and hype them up. This has dire consequences for peace and democracy in South Asia, particularly between India and Pakistan.

The Indian mainstream media is largely filled with war-mongering, frothing-at-the-mouth television anchors and screaming headlines based on political statements supporting a hate-filled rhetoric. This gives the impression that the entire country supports these views. Such elements are visible in the Pakistani media too, but the commentary has on the whole been far more temperate for some time now.

The violent narrative that overwhelms public discourse leaves little space for reasonable voices or any nuance or positivity. Yet many on the ground engaged in work that generates positivity continue to do that work, for example in the areas of health, education, peace-building and empowerment of marginalized communities. Their efforts rarely make the news.

The suicide attack on a military convoy in Pulwama in the Indian-administered Kashmir in February 2019 marked a low point in media coverage of the fraught relations between India and Pakistan. Post-Pulwama, public narratives in India and Pakistan were exceedingly polarized. Newspapers, TV channels, websites and social media timelines were filled with glorifying and justifying actions of the “home team” as it were. Those attempting to question these narratives are subjected to a barrage of abuse and accusations of being ‘traitor’.

The lack of transparency on both sides of the border makes it difficult to know what really happened in a conflict situation. When soldiers or civilians are injured or killed in ceasefire violations at the Line of Control in the disputed region of Kashmir, the governments and media of both Pakistan and India only report their own side’s casualties. Both claim “unprovoked” firing from across the border.

The possibilities of peace

Trolls and those pushing fascist, violent agendas have taken to social media in an organised way. Recognising its value, they are using it effectively to push their narratives in the public domain. Many are paid to do this. As they do so, they create space for those who agree with their views to come online and publicly say what was unacceptable before.

These paid armies and their associate volunteers are crowding out the original promise of social media – more space for pluralism, peace, and democracy. But the original dream is also still very much alive, even if those upholding it are not as well-organised or paid.

According to Facebook data, 2,604,986 Facebook users from India and Pakistan connected as ‘friends’ on 4 March 2018, from its site, www.fb.com/peace, that provided data on how many people formed friendships daily across three conflict zones. (This the same figure as on 26 December 2017 so perhaps Facebook had stopped updating the numbers before discontinuing the tool). The average for India and Pakistan, going by numbers updated daily, was around 250,000 pretty much any day. This indicates at least a level of curiosity if not aspirations for peace and friendship across borders, that social media platforms provide space for.

An unprecedented – perhaps in the world – example of cross-border media cooperation with a specific agenda for peace building that continues to be a platform for such aspirations is Aman Ki Asha (Hope for Peace). The two large media groups behind it, Jang Group of Pakistan and the Times of India, that launched it on 1 January 2010 may have lost interest in this CSR over the past few years but it continues to be a good example of reporting about a cause - journalism combined with peace activism.

For the first few years, Aman Ki Asha music and literary festivals, economic symposiums and seminars discussing strategic issues, were organised in cities around India and Pakistan. The Jang Group and TOI reported on these events in their newspapers, sometimes as full-page supplements; the Jang Group’s Geo TV also broadcast reports about these events. Often other media, however, chose not to cover such events as most publications then would not name or promote any activity by their professional rivals.

In Pakistan, the Jang Group also published a weekly Aman Ki Asha page in its English and Urdu papers until 2014. The printed pages were dropped due to commercial and other pressures, but the editor continues to curate, commission, and edit material for the website from where it is shared to the Aman Ki Asha social media accounts and beyond.

The platform has since its launch consistently provided a space for “peace mongers” in the region. Young people often message the Facebook page with initiatives and ideas that Aman Ki Asha takes up and works with editorially. The content produced for the website and in the social media platforms helps counter the jingoism and war rhetoric played up by the mainstream media.

On April 3, 2019, when actor Bushra Ansari released a music video based on a peace poem by her older sister Neelum Bashir, Neelum asked a young friend in India (who actually started and manages her other actor sister Asma’s Facebook fan page) to share it with Aman Ki Asha on Facebook. The video was posted to the AKA Facebook Page and Twitter feed, and shared in the AKA group and elsewhere by countless members. The song, performed as a duet between two neighbours separated by an insurmountable wall went viral, forcing the mainstream media to take it up.

The video’s popularity in India and in Pakistan cuts through the political rhetoric against either country. This is just one indication of the people’s aspirations for peace and good relations between the two countries, drowned out by the din of warmongering dominating the airwaves and social media, but still alive and kicking.

[This article is based upon extracts from “Truth vs Misinformation: South Asia Press Freedom Report 2018-19” which can be accessed here https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1VZyAfj_GrbEkdN0pOEaxo1RrZrSgRIOk]