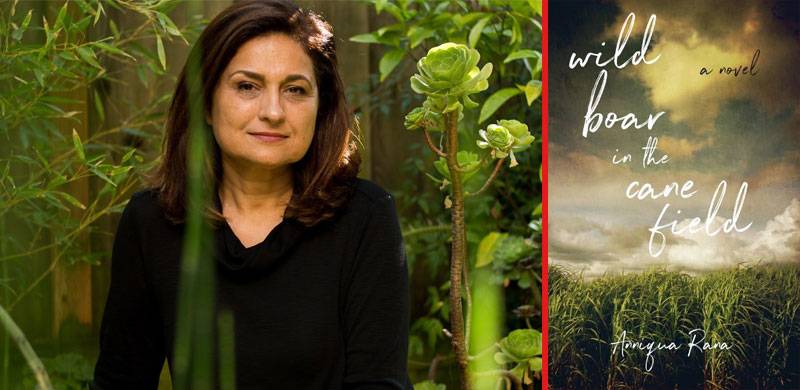

We're publishing an excerpt from Anniqua Rana's forthcoming novel 'Wild Boar in the Cane Field' that "depicts the tragedy that often characterizes the lives of those who live in South Asia—and demonstrates the heroism we are all capable of even in the face of traumatic realities."

“I look at the stars and I see you,” Maalik said the night we moved our charpoys outdoors. In my seventh month of pregnancy, the airless mud hut suffocated me. The smell of cow dung and the fear of wild boar were preferable to our one-room home, ventilated only by the cracks in the wooden door.

The rough rope of the charpoy dug into my left hip bone as I peered into the darkness at Maalik’s two dogs, sitting apart and protecting the buffalo, which stood at some distance from our hut, chewing cud. I could understand why Maalik was mesmerized by these animals he cared for. Their slow, hypnotic movements as they ate, as they chewed, and as they blinked their enormous eyes, consumed my thoughts.

I slipped into a space inside myself as I felt Maalik’s breathing beside me. We had left the other charpoy in the room, so I lay with my back to him, while he reclined on the pillow we shared, looking up at the star-filled sky, puffing clouds of bidi smoke toward them.

A mosquito buzzed above my head, and I sensed the quick movement of Maalik’s hand silence it. We lay in silence for some time, and then the two dogs lifted their heads and stared into the rustling fields.

Maalik explained sleepily, “That’s not a breeze. Those are wild boars nesting their young. On some nights, they peer out of the fields and look at the buffalo, and I see the sparkle in their eyes. But I pick up the gun that Saffiya gave me, and they disappear.”

Could boars distinguish between a stick and a rifle? I wondered, but I remained silent, wondering if they chose to listen to our whisperings in the night. A wild boar had bitten off Bhaggan’s uncle’s foot many years earlier, before I was born. I imagined the pain that might cause and felt my baby flutter inside me. I rubbed my stomach to calm her down. My heart began thumping, nourishing my fear. I squinted into the darkness of the fields, searching for the shine of a boar’s eyes.

My fear reminded me of the night Taaj dared Maria and me to listen to the ghosts of her mother’s dead babies at the canal bank. Our own reflections in the dark waters terrified us. At night, the menace of silent shadows, howling hyenas, and wild boars was treacherously magnified, but I buried my panic deep inside.

The dogs placed their heads down again. The danger had passed.

Our bodies touched briefly as Maalik shifted his weight to pull another bidi from his pocket. I was used to his silence during the day, but at night the fumes of his bidi opened his mind and made him talk. He never expected me to respond. He talked and I listened.

“Sultan died and Taaj left, and I sat by myself with the buffaloes. On the canal bank, I watched them dip in and out of the water and stared at the sun sinking into the horizon. Fireflies shone over the glistening black buffalo. And I thought of you.”

In the past months, I had learned how different Maalik was from my perception of him when we were young. As children, Taaj and I had made fun of him. Laughed when he repeated himself consistently. Ignored him when he talked out of turn.

Now Taaj was gone. He had not returned since the night we had slept together. His memory was blurring because of the memories I was creating with Maalik. I could remember his handsome face and his laugh. Maalik never laughed, and he wasn’t as handsome, but his thoughts were deeper. I had never heard anyone talk about the things he discussed. And he never talked about them in the daytime.

But when we lay together at night, he was a different person. He shared his thoughts, sometimes beautiful and sometimes strange. Like his mother, he told stories, but they were different. They were about what he believed had happened in our lives. And they started and ended abruptly, with no connection to each other. I never interrupted or asked questions. He told his stories as if he were talking to himself.

I lay beside him, imagining his world.

“You were like the smoldering sun to others. The sun that killed Sultan and lured Taaj. But for me, you’re a star. Just like your name. A star that tells me where to go. The village men and women, they laugh at me. They say you made a fool of me. But I am no fool. They don’t know what I know. They didn’t see what I see. You needed someone to protect you.”

He took a deep puff of his bidi. “Taaj was the fool. You gave yourself to him. Look at what he did. He left you. But I knew better. He pretended he was smarter than I was. He laughed at me. You did, too. But I didn’t care. So long as you noticed me. The villagers, they don’t realize that’s all I need.”

Maalik had told me this before. My existence was all he needed. I couldn’t understand. Was this love? Did I feel the same way for him?

He became more animated as he spoke. “Tara. Allah is my witness. The stars are my witness. If anything happened to you, I would kill myself. Life without you would be my death.”

This took me by surprise. He was professing his love for me, but I felt nothing.

My baby inside me kicked for attention, and I stroked her to calm her down.

“The day we were married, I knew I had caught a star that I could keep. Like the fireflies. But they would die when I clutched them in my fist. Their light dissolved. But you, Tara, my star, you’re with me, and you shine.”

I stretched my foot to relieve the cramp I felt and thought of the past seven months as his wife, living in the hovel near the cane fields. Every morning I bathed in the canal before the field hands began their work. On the outdoor stove, my kitchen, I made the morning roti and cane-sweetened tea for both of us. I wrapped a piece of mango pickle in a roti for Maalik’s afternoon meal when he took the buffalo to water.

Every day I walked the long distance through the fields to Saffiya’s house to help Bhaggan prepare the meals of the day and returned before sundown.

Maalik was not a demanding husband. On Eid day, he brought me a pair of green leather slippers with gold embroidery that absorbed the dust from the unpaved paths I walked and became brown. They also became soft, and as I slid my feet into them, I was reminded of the comfort I was becoming accustomed to in my new life. I did a lot of what I had done before I had married Maalik, but now I did not have anyone telling me what to do.

Every day, I cooked meals that I served to others; every other day, I warmed the soap and washed clothes; and once a month, Maria and I made dung cakes to build the fires to cook the meals and warm the soap. But I did this knowing it was what I did well. All the while, my baby was growing inside me.

Maalik and Bhaggan became the two poles of my existence. I started and ended my days with him. I spent the time in between with Bhaggan in Saffiya’s kitchen. She seemed to have forgotten her grudge about having to pay for our wedding. What else would she have done but spend her time in the kitchen? That was all she had ever done. She didn’t know anything else.

At times the two of them blurred into one: hazel eyes, adoration for the dead and disappeared.

Without a pause, Maalik switched from me to his brothers.

“Sultan was like a god. I remember him so well. Do you remember him? My hair, it’s not like his. His was always combed back. Mine curls. What do you think Taaj is doing now? Does he think of us? Amman waits for him to return.”

He always became more excited after his second bidi.

“And remember that time in the garden when Taaj said you would marry Sultan? But you didn’t. You married me instead. Isaac said we shouldn’t break flowers from the garden. Even now, I understand what he says better than anyone else. Better than his daughter. He can’t talk, but I know what he’s signing.”

He placed his hand on his heart and then pointed at me.

“You know what that means? It means I care for you. People think he’s not smart because he can’t talk. Like me. I talk, but they think I don’t know enough. But look. I married you, and we’ll have a baby.”

I had never known that he was close to Maria’s father, Isaac. There were so many things that I had never noticed that Maalik had told me in the past seven months.

As always happened, I was beginning to feel drowsy and drifted into a half sleep. Suddenly, the dogs began barking and I awoke. Maalik was no longer lying beside me. I looked around, but he was gone. I panicked. Where could he have gone at this time of night? Why had he left me alone?

Usually he woke me up before he left to check the buffalo or went to relieve himself, and this bothered me. I had complained to him and told him to let me sleep, rather than announcing his departure. But that didn’t stop him from continuing to wake me, so what had happened now? Why had he left without waking me?

I was too scared to go look for him, so I sat upright on the charpoy with my chador wrapped tightly around me. I peered into the night, into the depths of the cane field, hoping to see him appear, and then I heard a crunch behind me.

“What?” he said, as I stared nervously in his direction. “You’ve told me so many times not to wake you. And now you’re upset that I didn’t.”

He pulled at his clothes, and I realized he had just gone to relieve himself. He lay down beside me, and I settled down, too, placing my hand on his shoulder. His callused hand covered mine as we fell asleep.

The next morning, Bhaggan took me to see the midwife in the next village. The hour-long walk left Bhaggan panting and holding her side. We stopped every ten minutes for her to catch her breath.

“Why, Amman? Have you been staying up at night, praying for Sultan?” I asked her.

She burped loudly. “No, my daughter. I ate the curry that Hamida’s mother brought over. It’s given me indigestion.” But I had seen her with indigestion before. It didn’t leave her breathless this way. I wondered if her concern about the debt or Taaj’s disappearance had weakened her, but she soon let me know what was troubling her.

“Can you believe her?” she panted, as we walked along the dusty path. I knew Bhaggan was referring to Saffiya. “She can’t find her earrings, and she says Taaj must have taken them when he disappeared.”

I reached out for her hand as she stumbled on a rock. I held it tight and said nothing.

I had forgotten about the earrings. Why would Saffiya think of them now, after all this time? She hadn’t mentioned them to me when I had placed her ironed clothes in her closet, so why did she need them? It was the month of fasting, and there was no marriage for her to attend where she would need them.

“She says she put them under the Holy Book a month before your wedding. My son might be irresponsible, but he’s not a thief. How dare she!” She stopped again and pointed to a nearby small mud boundary wall near the canal. “There,” she said. “I need to sit down for a bit.”

I followed her to the temporary seat she had found under the neem tree. She was panting more than usual.

“I didn’t fast today. I couldn’t wake up on time. I hope I’m forgiven.” Bhaggan didn’t say the five daily prayers but I had never known her to miss the day-long fasts.

“You didn’t fast, did you?” she asked me. “It’ll harm the baby.”

I shook my head, still thinking about the earrings. I’d forgotten about them because I would never have occasion to wear them. I realized I needed to return them before they created more problems.

I had planned to wear them to the movie theater with Taaj, but so much had happened, and we had never gone. And I had kept them hidden in the corner of my old bedroom that I shared with Bhaggan. I had forgotten to return them. I had no use for them in my new life with Maalik in the cane fields, but I needed to find a way to put them back before they created more problems.

“Tomorrow I’ll go and organize her closet. I’m sure they’re where she put them,” I consoled Bhaggan.

“Wait till you hear what the midwife says. I’m going to ask her to show you the flower of Maryam, which will calm you during childbirth. I don’t want my grandchild to come before his time. And what does Saffiya need the earrings for, anyway? She’s close to her time to meet her maker. She’ll need only a white sheet to wrap her then. Everything will be left here, the old hag!”

Bhaggan was as convinced that the baby was a boy as I was that she was a girl. I knew I was right, though. She had spoken to me through her movements. She had kicked me gently from within when I had called her by her name: Shahida, the witness.

I had learned the meaning of the male version of the name, Shahid, when studying the Holy Book with Zakia. I liked it. When I told Maalik, he liked it, too.

And now that I was confident I would have a girl of my own, I would call her Shahida. But there was no deterring Bhaggan, and no reason to. Soon enough, Shahida would be with us.

And I knew the birth would be easy. I was strong and had never suffered any illness or injury, and bringing my first baby into the world would not be difficult. I was confident and urged Bhaggan to move a bit faster and get to the midwife’s house, which was now just down the road from us.

I decided I’d return the earrings the next day, to reduce Bhaggan’s concern and to take the blame off Taaj.

“I look at the stars and I see you,” Maalik said the night we moved our charpoys outdoors. In my seventh month of pregnancy, the airless mud hut suffocated me. The smell of cow dung and the fear of wild boar were preferable to our one-room home, ventilated only by the cracks in the wooden door.

The rough rope of the charpoy dug into my left hip bone as I peered into the darkness at Maalik’s two dogs, sitting apart and protecting the buffalo, which stood at some distance from our hut, chewing cud. I could understand why Maalik was mesmerized by these animals he cared for. Their slow, hypnotic movements as they ate, as they chewed, and as they blinked their enormous eyes, consumed my thoughts.

I slipped into a space inside myself as I felt Maalik’s breathing beside me. We had left the other charpoy in the room, so I lay with my back to him, while he reclined on the pillow we shared, looking up at the star-filled sky, puffing clouds of bidi smoke toward them.

Also read: You, My Father

A mosquito buzzed above my head, and I sensed the quick movement of Maalik’s hand silence it. We lay in silence for some time, and then the two dogs lifted their heads and stared into the rustling fields.

Maalik explained sleepily, “That’s not a breeze. Those are wild boars nesting their young. On some nights, they peer out of the fields and look at the buffalo, and I see the sparkle in their eyes. But I pick up the gun that Saffiya gave me, and they disappear.”

Could boars distinguish between a stick and a rifle? I wondered, but I remained silent, wondering if they chose to listen to our whisperings in the night. A wild boar had bitten off Bhaggan’s uncle’s foot many years earlier, before I was born. I imagined the pain that might cause and felt my baby flutter inside me. I rubbed my stomach to calm her down. My heart began thumping, nourishing my fear. I squinted into the darkness of the fields, searching for the shine of a boar’s eyes.

My fear reminded me of the night Taaj dared Maria and me to listen to the ghosts of her mother’s dead babies at the canal bank. Our own reflections in the dark waters terrified us. At night, the menace of silent shadows, howling hyenas, and wild boars was treacherously magnified, but I buried my panic deep inside.

The dogs placed their heads down again. The danger had passed.

Also read: Translation of “23 March, 1973” by Fahmida Riaz

Our bodies touched briefly as Maalik shifted his weight to pull another bidi from his pocket. I was used to his silence during the day, but at night the fumes of his bidi opened his mind and made him talk. He never expected me to respond. He talked and I listened.

“Sultan died and Taaj left, and I sat by myself with the buffaloes. On the canal bank, I watched them dip in and out of the water and stared at the sun sinking into the horizon. Fireflies shone over the glistening black buffalo. And I thought of you.”

In the past months, I had learned how different Maalik was from my perception of him when we were young. As children, Taaj and I had made fun of him. Laughed when he repeated himself consistently. Ignored him when he talked out of turn.

Now Taaj was gone. He had not returned since the night we had slept together. His memory was blurring because of the memories I was creating with Maalik. I could remember his handsome face and his laugh. Maalik never laughed, and he wasn’t as handsome, but his thoughts were deeper. I had never heard anyone talk about the things he discussed. And he never talked about them in the daytime.

But when we lay together at night, he was a different person. He shared his thoughts, sometimes beautiful and sometimes strange. Like his mother, he told stories, but they were different. They were about what he believed had happened in our lives. And they started and ended abruptly, with no connection to each other. I never interrupted or asked questions. He told his stories as if he were talking to himself.

I lay beside him, imagining his world.

“You were like the smoldering sun to others. The sun that killed Sultan and lured Taaj. But for me, you’re a star. Just like your name. A star that tells me where to go. The village men and women, they laugh at me. They say you made a fool of me. But I am no fool. They don’t know what I know. They didn’t see what I see. You needed someone to protect you.”

Also read: A Hundred Journeys: Personal Tale Intermingled With Social Landscape

He took a deep puff of his bidi. “Taaj was the fool. You gave yourself to him. Look at what he did. He left you. But I knew better. He pretended he was smarter than I was. He laughed at me. You did, too. But I didn’t care. So long as you noticed me. The villagers, they don’t realize that’s all I need.”

Maalik had told me this before. My existence was all he needed. I couldn’t understand. Was this love? Did I feel the same way for him?

He became more animated as he spoke. “Tara. Allah is my witness. The stars are my witness. If anything happened to you, I would kill myself. Life without you would be my death.”

This took me by surprise. He was professing his love for me, but I felt nothing.

My baby inside me kicked for attention, and I stroked her to calm her down.

“The day we were married, I knew I had caught a star that I could keep. Like the fireflies. But they would die when I clutched them in my fist. Their light dissolved. But you, Tara, my star, you’re with me, and you shine.”

I stretched my foot to relieve the cramp I felt and thought of the past seven months as his wife, living in the hovel near the cane fields. Every morning I bathed in the canal before the field hands began their work. On the outdoor stove, my kitchen, I made the morning roti and cane-sweetened tea for both of us. I wrapped a piece of mango pickle in a roti for Maalik’s afternoon meal when he took the buffalo to water.

Every day I walked the long distance through the fields to Saffiya’s house to help Bhaggan prepare the meals of the day and returned before sundown.

Maalik was not a demanding husband. On Eid day, he brought me a pair of green leather slippers with gold embroidery that absorbed the dust from the unpaved paths I walked and became brown. They also became soft, and as I slid my feet into them, I was reminded of the comfort I was becoming accustomed to in my new life. I did a lot of what I had done before I had married Maalik, but now I did not have anyone telling me what to do.

Every day, I cooked meals that I served to others; every other day, I warmed the soap and washed clothes; and once a month, Maria and I made dung cakes to build the fires to cook the meals and warm the soap. But I did this knowing it was what I did well. All the while, my baby was growing inside me.

Also read: ‘I don’t see hostility going on indefinitely’: Romila Thapar on Pak-India relations and more

Maalik and Bhaggan became the two poles of my existence. I started and ended my days with him. I spent the time in between with Bhaggan in Saffiya’s kitchen. She seemed to have forgotten her grudge about having to pay for our wedding. What else would she have done but spend her time in the kitchen? That was all she had ever done. She didn’t know anything else.

At times the two of them blurred into one: hazel eyes, adoration for the dead and disappeared.

Without a pause, Maalik switched from me to his brothers.

“Sultan was like a god. I remember him so well. Do you remember him? My hair, it’s not like his. His was always combed back. Mine curls. What do you think Taaj is doing now? Does he think of us? Amman waits for him to return.”

He always became more excited after his second bidi.

“And remember that time in the garden when Taaj said you would marry Sultan? But you didn’t. You married me instead. Isaac said we shouldn’t break flowers from the garden. Even now, I understand what he says better than anyone else. Better than his daughter. He can’t talk, but I know what he’s signing.”

He placed his hand on his heart and then pointed at me.

“You know what that means? It means I care for you. People think he’s not smart because he can’t talk. Like me. I talk, but they think I don’t know enough. But look. I married you, and we’ll have a baby.”

I had never known that he was close to Maria’s father, Isaac. There were so many things that I had never noticed that Maalik had told me in the past seven months.

As always happened, I was beginning to feel drowsy and drifted into a half sleep. Suddenly, the dogs began barking and I awoke. Maalik was no longer lying beside me. I looked around, but he was gone. I panicked. Where could he have gone at this time of night? Why had he left me alone?

Usually he woke me up before he left to check the buffalo or went to relieve himself, and this bothered me. I had complained to him and told him to let me sleep, rather than announcing his departure. But that didn’t stop him from continuing to wake me, so what had happened now? Why had he left without waking me?

Also read: Ahmad Bashir (1923-2004): Dancer With Wolves

I was too scared to go look for him, so I sat upright on the charpoy with my chador wrapped tightly around me. I peered into the night, into the depths of the cane field, hoping to see him appear, and then I heard a crunch behind me.

“What?” he said, as I stared nervously in his direction. “You’ve told me so many times not to wake you. And now you’re upset that I didn’t.”

He pulled at his clothes, and I realized he had just gone to relieve himself. He lay down beside me, and I settled down, too, placing my hand on his shoulder. His callused hand covered mine as we fell asleep.

The next morning, Bhaggan took me to see the midwife in the next village. The hour-long walk left Bhaggan panting and holding her side. We stopped every ten minutes for her to catch her breath.

“Why, Amman? Have you been staying up at night, praying for Sultan?” I asked her.

She burped loudly. “No, my daughter. I ate the curry that Hamida’s mother brought over. It’s given me indigestion.” But I had seen her with indigestion before. It didn’t leave her breathless this way. I wondered if her concern about the debt or Taaj’s disappearance had weakened her, but she soon let me know what was troubling her.

“Can you believe her?” she panted, as we walked along the dusty path. I knew Bhaggan was referring to Saffiya. “She can’t find her earrings, and she says Taaj must have taken them when he disappeared.”

I reached out for her hand as she stumbled on a rock. I held it tight and said nothing.

I had forgotten about the earrings. Why would Saffiya think of them now, after all this time? She hadn’t mentioned them to me when I had placed her ironed clothes in her closet, so why did she need them? It was the month of fasting, and there was no marriage for her to attend where she would need them.

Also read: From Lucknow to Larkana

“She says she put them under the Holy Book a month before your wedding. My son might be irresponsible, but he’s not a thief. How dare she!” She stopped again and pointed to a nearby small mud boundary wall near the canal. “There,” she said. “I need to sit down for a bit.”

I followed her to the temporary seat she had found under the neem tree. She was panting more than usual.

“I didn’t fast today. I couldn’t wake up on time. I hope I’m forgiven.” Bhaggan didn’t say the five daily prayers but I had never known her to miss the day-long fasts.

“You didn’t fast, did you?” she asked me. “It’ll harm the baby.”

I shook my head, still thinking about the earrings. I’d forgotten about them because I would never have occasion to wear them. I realized I needed to return them before they created more problems.

I had planned to wear them to the movie theater with Taaj, but so much had happened, and we had never gone. And I had kept them hidden in the corner of my old bedroom that I shared with Bhaggan. I had forgotten to return them. I had no use for them in my new life with Maalik in the cane fields, but I needed to find a way to put them back before they created more problems.

“Tomorrow I’ll go and organize her closet. I’m sure they’re where she put them,” I consoled Bhaggan.

Also read: Delhi Gate – A Bystander Of Various Ups and Downs Of Lahore

“Wait till you hear what the midwife says. I’m going to ask her to show you the flower of Maryam, which will calm you during childbirth. I don’t want my grandchild to come before his time. And what does Saffiya need the earrings for, anyway? She’s close to her time to meet her maker. She’ll need only a white sheet to wrap her then. Everything will be left here, the old hag!”

Bhaggan was as convinced that the baby was a boy as I was that she was a girl. I knew I was right, though. She had spoken to me through her movements. She had kicked me gently from within when I had called her by her name: Shahida, the witness.

I had learned the meaning of the male version of the name, Shahid, when studying the Holy Book with Zakia. I liked it. When I told Maalik, he liked it, too.

And now that I was confident I would have a girl of my own, I would call her Shahida. But there was no deterring Bhaggan, and no reason to. Soon enough, Shahida would be with us.

And I knew the birth would be easy. I was strong and had never suffered any illness or injury, and bringing my first baby into the world would not be difficult. I was confident and urged Bhaggan to move a bit faster and get to the midwife’s house, which was now just down the road from us.

I decided I’d return the earrings the next day, to reduce Bhaggan’s concern and to take the blame off Taaj.