In this article, Nadeem F. Paracha takes you to the journey that Karachi went through over the course of centuries. Here's a history of Pakistan's largest, and world's 6th largest, city from the time Alexander the Great invaded subcontinent in 326 BC to date.

If you take a walk in any marketplace in Karachi, there is every likelihood that you would be able to hear five to six different languages. Urdu – rather its many dialects – is the most commonly spoken language here; but Pashtu, Punjabi, Balochi, Gujarati, Sindhi and even English, Bengali and Burmese can also be heard on the city’s streets.

There is also a possibility of you getting mugged. Even while waiting at a traffic signal. That’s Karachi. Mad and bad – and yet extremely diverse and progressive. And it’s big. Very big. It is the world’s sixth most populous city with a population of 14.91 million spread across an area of 3,780 km – and expanding.

326 BC: ‘Krokola’

When Alexander the Great’s armies that had invaded the subcontinent from the Khyber Pass in 327 BC began their exit from the region, they sailed down the River Indus in present-day Pakistan.

Whereas Alexander left for Babylon through a desert along the Makran Coast in Balochistan, one of his admirals, Nearchus, sailed out over the Arabian Sea from the shores of what became Karachi. Nearchus named the place ‘Krokola.’[1]

Population: N/A. But in ancient Greek writings, Krokola at the time had a few fishing villages inhabited by ‘primitive, fish-eating people.’

Economy: N/A.

Language: N/A

Religion: Probably animism.

Ethnicity: N/A.

Culture: Greek texts describe the few inhabitants that they encountered as being ‘primitive.’

Flora and Fauna: N/A. The Greeks only wrote about fish that the few residents caught and ate from the sea.

Crime: N/A.

12th Century CE: ‘Kalachi’

The area is mentioned again in the 12th century literature of Sindh’s Samma dynasty[2] that was based out of Thatta and is approximately 100 km from Karachi. A folk tale during this period spoke of a fisherman who went to ‘Kalachi’ to avenge the deaths of his six brothers who were swallowed by a whale in the sea. While in the sea looking for the whale, the man kills a large crocodile and is received as a hero.

Population: N/A. Probably still sparse and living in small fishing villages.

Economy: N/A.

Language: N/A

Religion: N/A

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi.

Culture: N/A.

Flora and Fauna: In Samma literature ‘Kalachi’ is described as being a sandy and arid area on the shores of a mighty sea. Folklore based in this area speak of whales and crocodiles. This means the seas of Karachi had whales and saltwater crocodiles.

Crime: N/A.

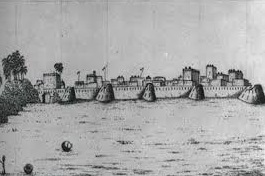

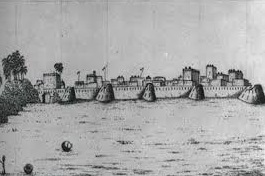

1794 CE: ‘Kolachi Jo Kun’

Even though Arab and Turkish navigators had marked the area as ‘Ras Karashi’ and ‘Kaurashi’[3] on maps in the 15th and 16th centuries, it was still seen as an insignificant backwater location with fishing villages.

In 1794 Sindh’s Talpur dynasty brought the area under its control (from the Kalhora rulers). The location began appearing on maps as a town. The Talpurs fortified it with mud walls and according to texts of the period the town was known as ‘Kolachi Jo Kun’[4] or or Kolachi’s well.

Population: Approximately 5000.[5]

Economy: Based on fishing and some sea trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi.

Religion: Mixed: Largely Hindu with a growing Muslim population.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi; Some Baloch.

Culture: N/A.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: Later British records talk about brothels, opium dens and gambling houses.

1839-57 CE: ‘Kowrachee Town’.

In 1839, armies of the British East India Company defeated the Talpurs and conquered Karachi. They called it ‘Kowrachee Town’ and/or ‘Kuraachee.’

The British began to develop Karachi’s port and introduced local governance overseen by British officials. A policing system was also introduced and modern methods of taxation. In 1858, the British East India Company was abolished and Karachi, like the rest of India, became part of the British Crown.

Population: 56,875.[6]

Economy: Based on fishing and sea trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi and some Balochi dialects. The British introduced English.

Religion: Largely Hindu and Muslim.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi; Some Baloch.

Culture: British writings of the period describe a lively but ‘filthy’ town of about fifty thousand people.[7] The same writings explained the men of this town as being ‘hard working but boisterous’ and the women as ‘loud but fond of wearing bright coloured clothes.’[8] The men loved to fight, gamble and drink. Most were fishermen.

Flora and Fauna: British texts mention eagles (kites), crows, pigeons, seagulls and parrots as the main birds. Dogs, cats, foxes, wolves, swine, snakes, crocodiles, camels, scorpions and all kind of fish are also mentioned. The land was mostly rough, sandy and covered with shrubs and mangroves. Palm trees were common.

Crime: British records mention brothels, opium dens and gambling houses.[9] Murder was rare but brawls between men were common.

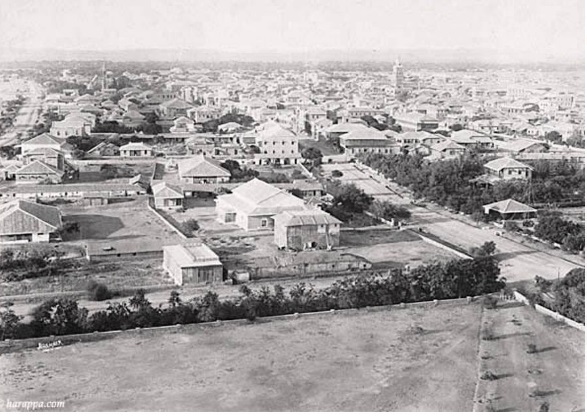

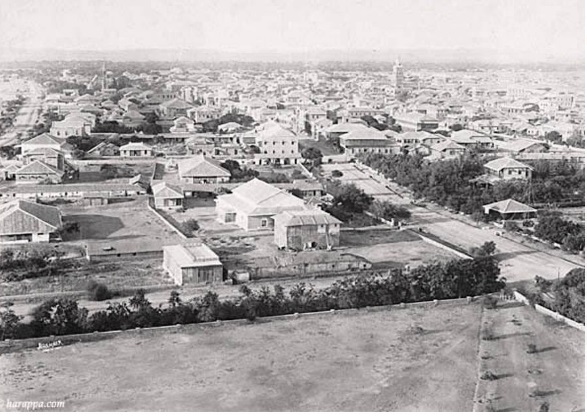

1860-1900: Karachi

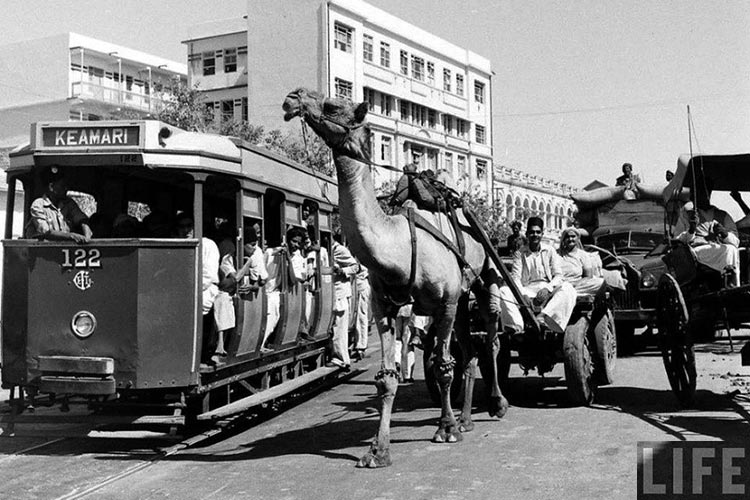

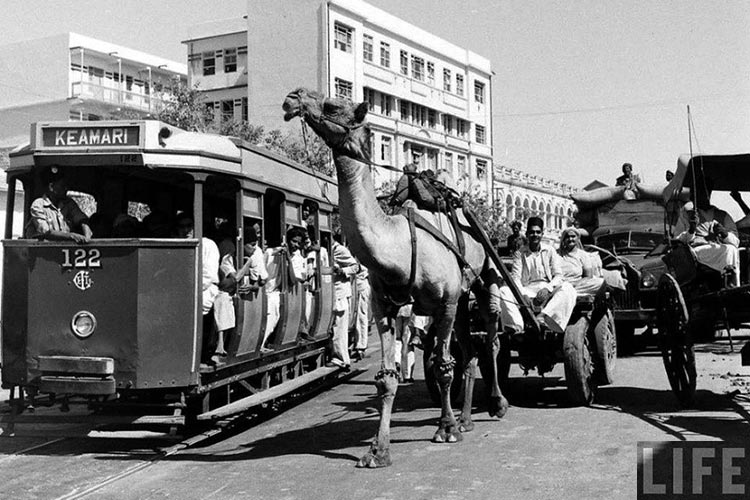

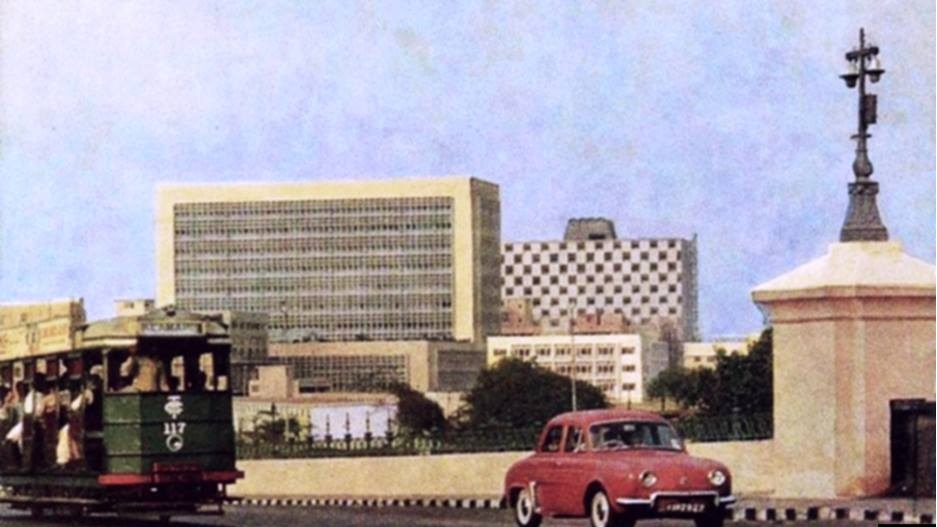

The British began initiating various infrastructural projects. With the development of the port, sea trade grew rapidly, attracting migrants from the rest of India. Railway lines were laid and the tramway introduced.

By 1870 Karachi had become the largest exporter of wheat and cotton to the rest of India.[10] In the 1890s, however, a bubonic plague killed hundreds of locals. As a consequence, the British began constructing an elaborate sewage and garbage collection system.

Population: 105,199[11]

Economy: Based on fishing and sea and land trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi and Balochi. English was increasingly used in official documents. Hindi too began to be spoken.

Religion: Hinduism followed by Islam. Christianity began to emerge as well.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi and Baloch. Indian Hindi-speakers and British English-speakers increased.

Culture: Pluralistic. Gambling and opium dens were closed and replaced with ‘posh’ clubs (for the British and the rich). Local drinking joints were replaced with pubs. Parks and theatres were constructed along with a cinema (Star Cinema). Hindu and Muslim religious festivals were tolerated. Christmas day was declared a holiday as well. Churches were built here for the first time.[12]

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees were most common. But the British also introduced some new flora brought from elsewhere in India. Eagles, crows, sparrows, seagulls, parrots and pigeons still ruled the skies. Cats, dogs, foxes, wolves, swine, cow, goats and camels walked the land. Number of horses increased. Texts of the period also speak of leopards and panthers attacking cattle in the less populated areas of Karachi. Whale, turtle, shark and dolphin sightings were frequent.

Crime: Compared to other cities of India, crime at the time in Karachi was low. Murder was rare, but cases of theft, inflicting physical injury and drunkard brawls increased.

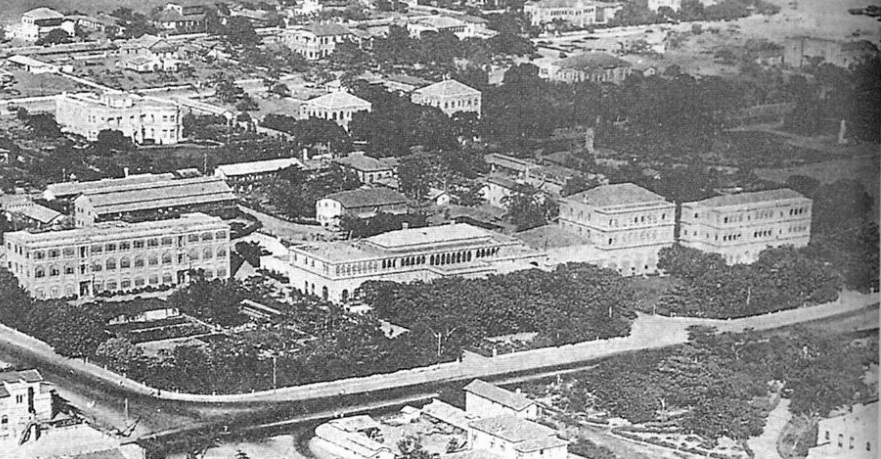

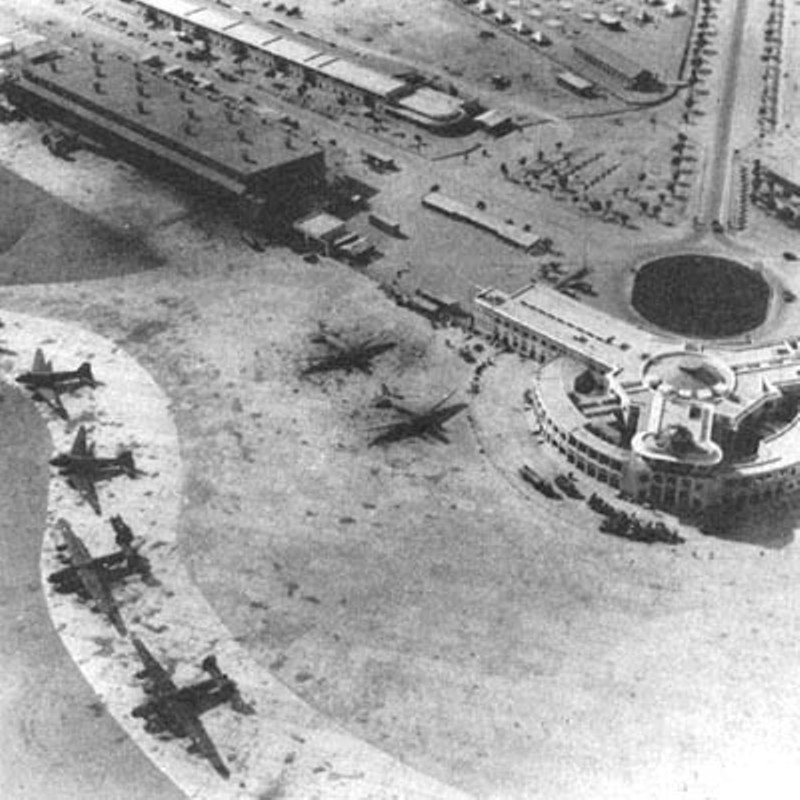

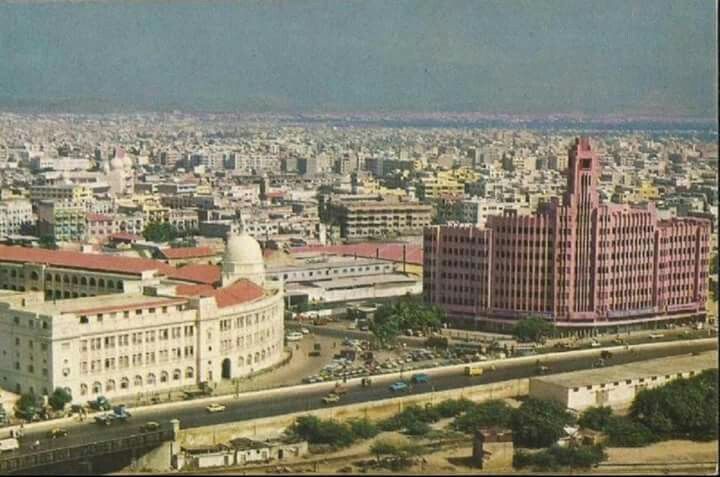

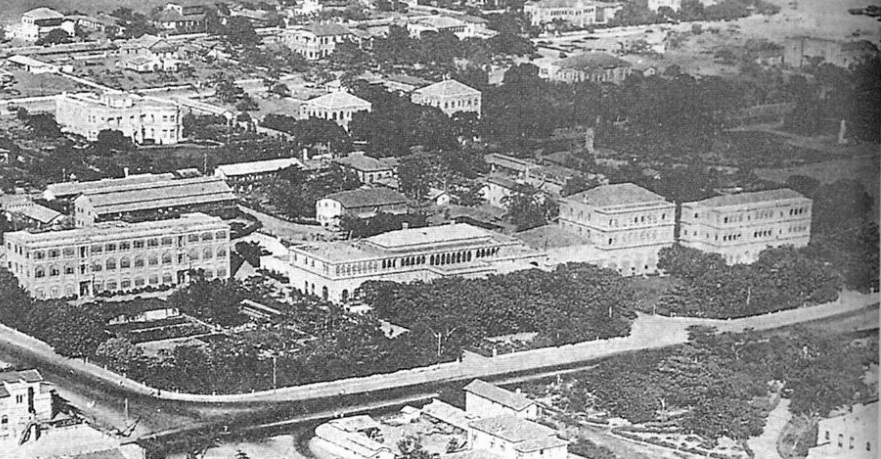

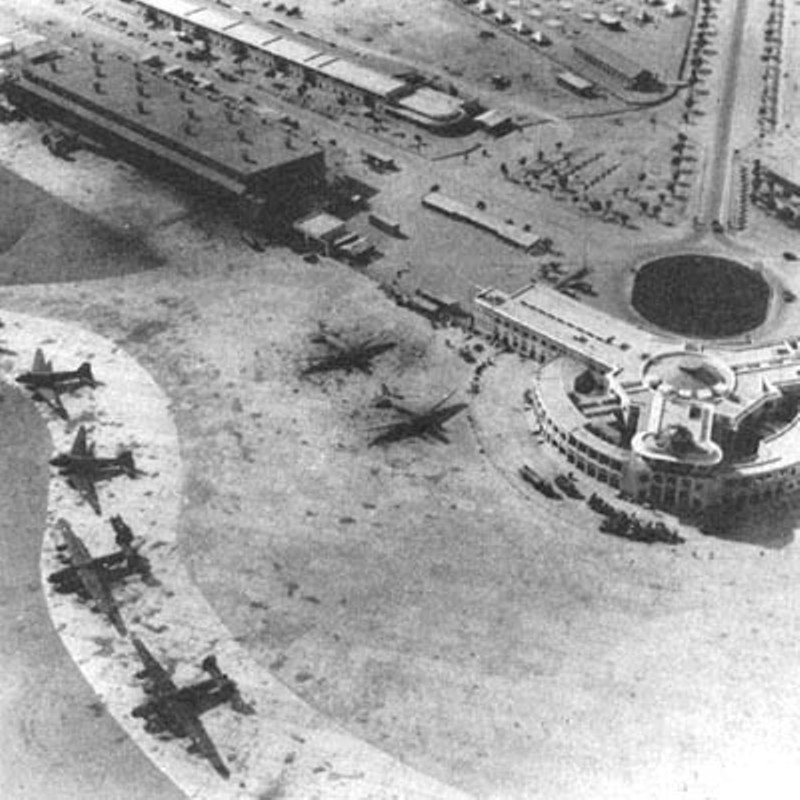

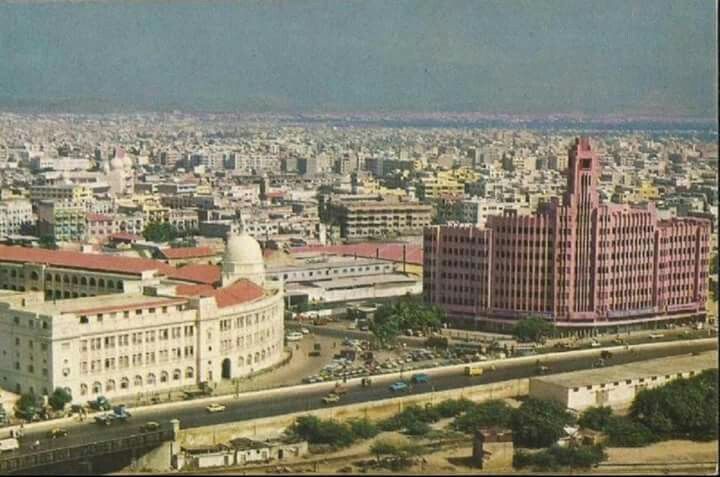

1901-1946: ‘Paris of the East’

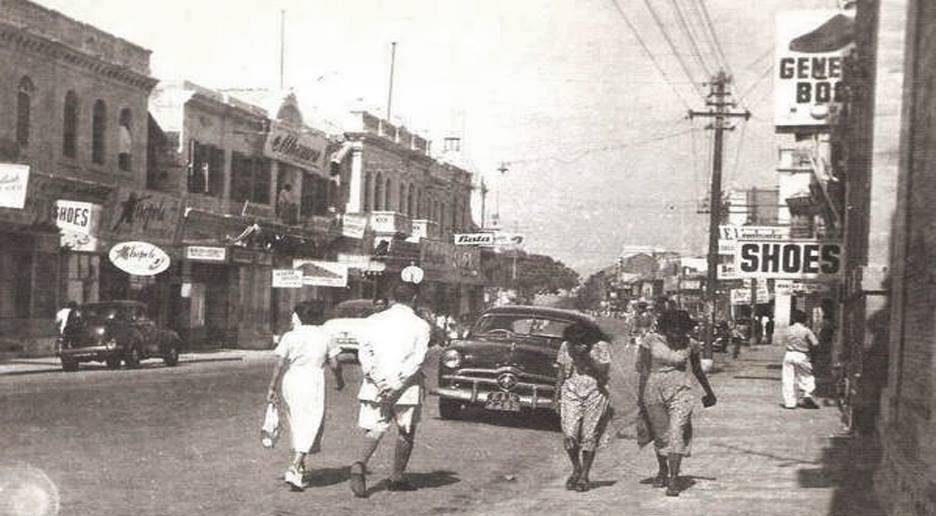

Karachi quickly emerged as an important economic hub of British India. Electricity was introduced and the economic boom attracted even more migrants. The British declared Karachi India’s most peaceful city. Some dubbed it the ‘Paris of the East.’

New residential areas, commercial buildings and roads (to now accommodate cars) were made and a strong local government system allowed Karachiites to elect their own mayor. However, the city’s older areas became congested with the arrival of migrant labour.

The first ever airport in India was built in Karachi.

Population: 435,887[13]

Economy: Fisheries; sea/air/land trade; banking; Insurance.

Language: Largely Sindhi and Balochi. English, Urdu, Gujarati and Hindi too became increasingly common.[14]

Religion: Hinduism (51%) and Islam (42%). Christianity (3.5%). Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Jain and Jewish communities constituted 5% of the population.

Ethnicity: Sindhi followed by Baloch, Hindi-speakers, Urdu-speakers, Punjabi, Memon, Goan and British.

Culture: Pluralistic. Texts of the period speak of ‘sound work ethics of Karachiites’. Number of parks, theaters, cinemas, beach-side resorts, pubs/bars, clubs, schools and collages increased. Karachi was least impacted by the ‘communal’ animosities between Hindu and Muslims present elsewhere in India.[15]

Flora and Fauna: New flora was introduced in parks and the Karachi Zoo. But palm trees remained a favourite. Population of leopards/panthers in the outskirts began to decline. So did the population of foxes and wolves.

Crime: Overall rate of crime remained low in Karachi compared to other major cities of India.[16] The policing system was good. However, crimes such as theft, brawling and petty-frauds were common in the more congested working-class areas.

1947-57: A City Turned On Its Head

Ironically, Hindus were in a majority in Karachi when in August 1947 the city became part of the newly-formed Pakistan. In 1948 Karachi was named Pakistan’s capital. By 1951, as the large influx of Urdu-speaking refugees from India (Mohajir) continued, and most of them began settling in Karachi, the Hindus began moving the other way and migrated to India.

Within a span of just three years, Karachi had a new majority: the Mohajir.

The city’s infrastructure was severely tested by the sudden growth of population and when thousands of Mohajirs who could not find a home, were settled in congested refugee camps.

This often caused tensions between the state and the new settlers in the shape of student riots. The city gradually began to lose its sheen.

Population: 1,068,459[17]

Economy: Fisheries; sea/land/air trade; banking.

Language: Urdu replaced Sindhi as the most spoken language of Karachi.[18] Sindhi-speakers declined. Punjabi-speakers increased, arriving from Punjab. Other languages spoken here were Balochi, Guajarati and English.

Religion: Islam became the majority religion. Christians, Zoroastrians, Hindus and Jews constituted about 6% of the city’s population.

Ethnicity: Mohajir majority, followed by Punjabi, Sindhi and Baloch minorities.

Culture: Since most Mohajirs arriving from various Indian cities were inherently cosmopolitan, Karachi retained its pluralistic character. Much of the literature and cinema emerging from the city during this period focused on the problems being faced by the Mohajir squatting in congested refugee camps. Since Karachi was the country’s capital and thus the most visited city of Pakistan, 5-star hotels and new cinemas began being built.

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees remained to be omnipresent and some new flora was introduced along roadsides and in parks. Population of eagles, sparrows, crows, pigeons, stray dogs and cats increased. The foxes and wolves vanished.

Crime: The crime rate shot up. It was most rampant in and around refugee camps.[19] The murder rate was still low, but pick-pocket gangs carrying blades and knives became ubiquitous.[20] Cases of corruption too increased.

1958-68: ‘City of Lights’

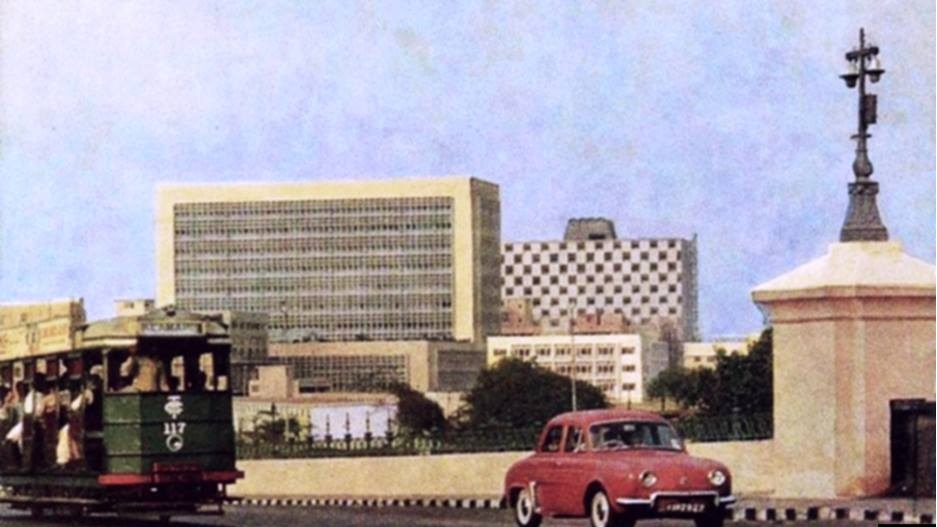

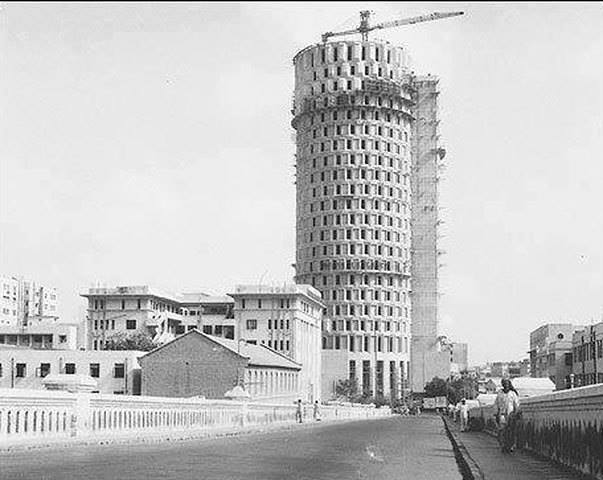

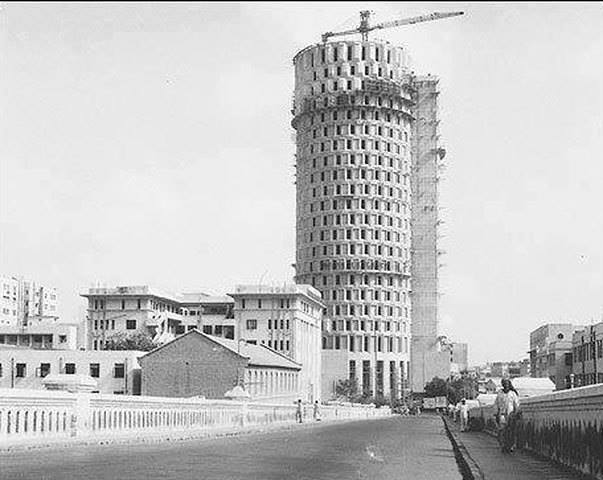

A year after army chief Ayub Khan took over power through a military coup in 1958, Karachi lost its status as the capital of Pakistan. But the city did become the epicenter of the regime’s robust industrialization policies.

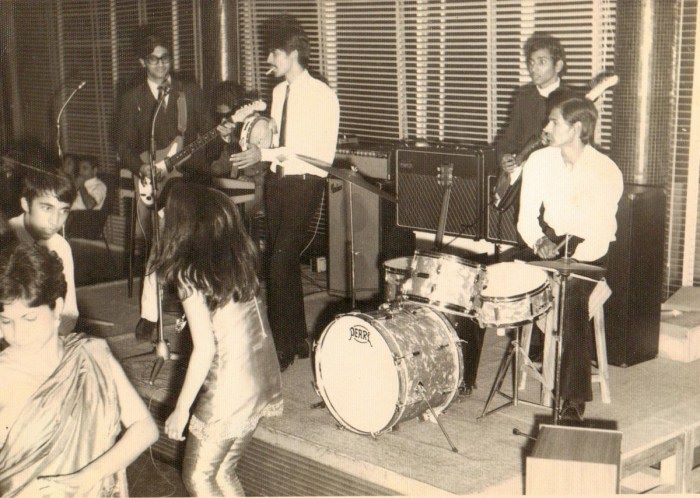

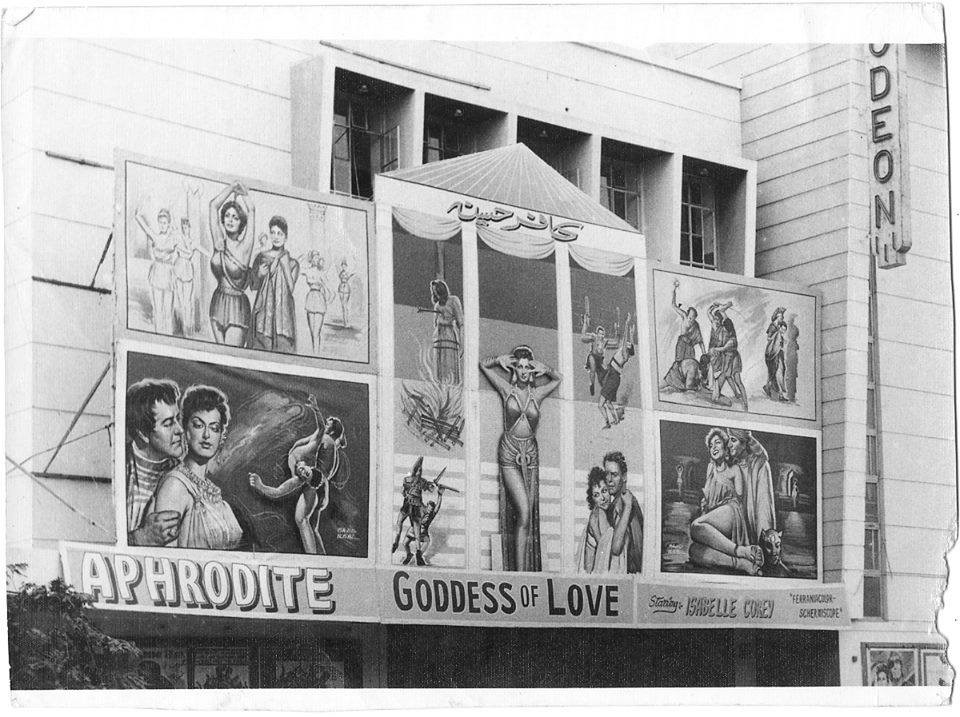

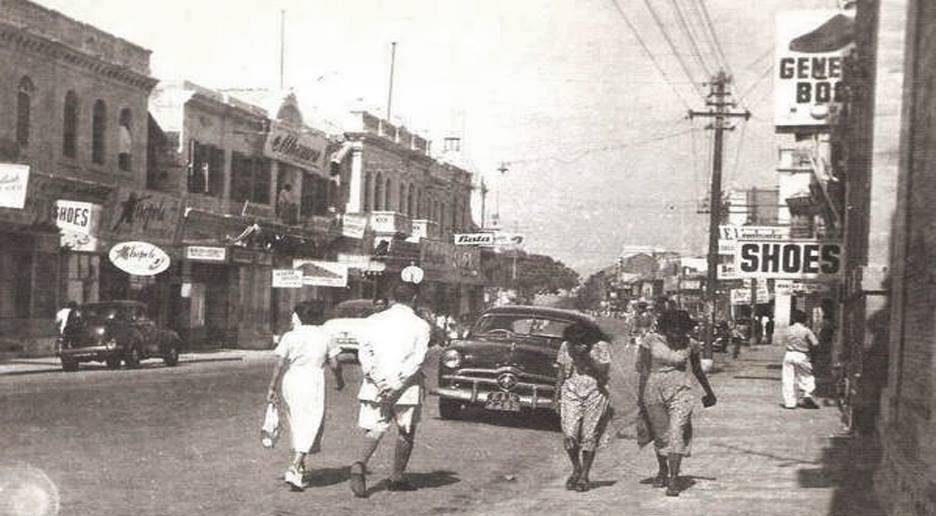

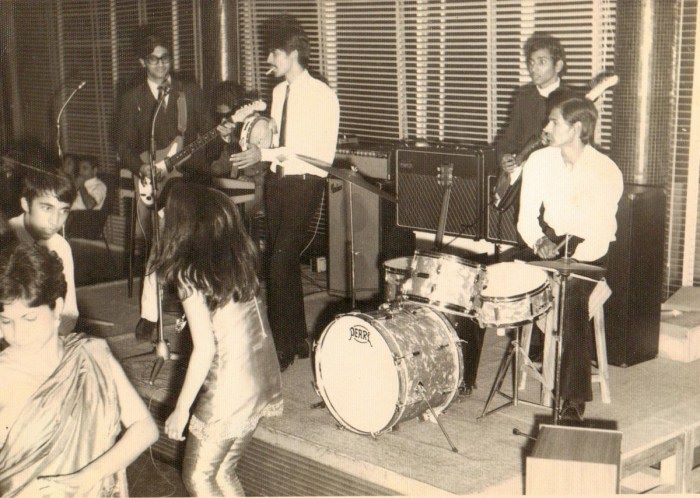

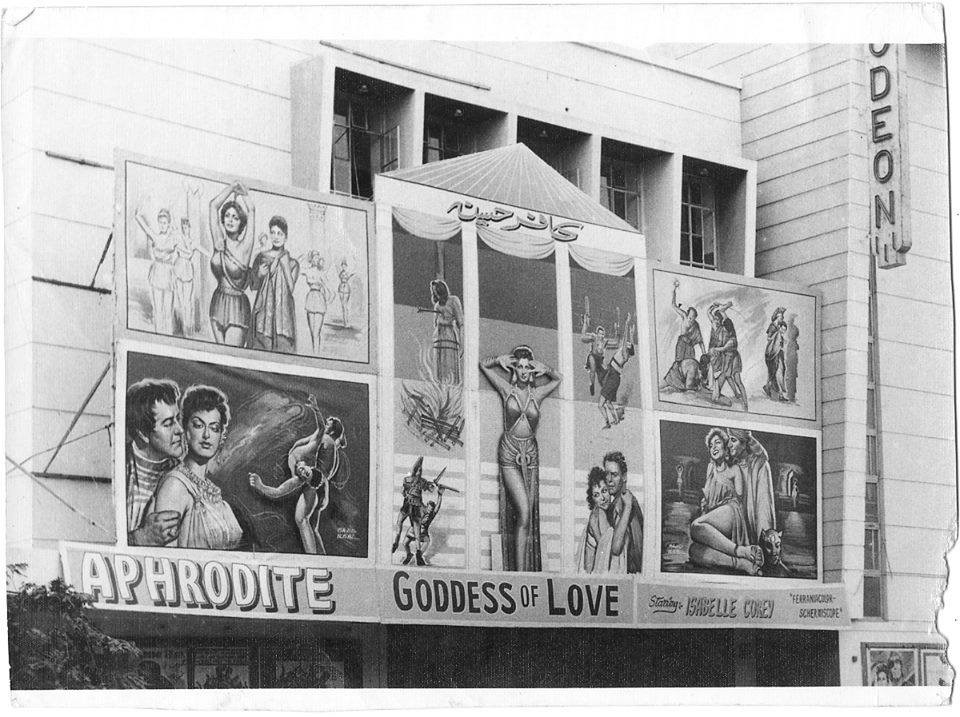

Economic activity in the city advanced at a rapid pace, attracting new migrants and reviving the city’s historic reputation as being an economic hub. New commercial buildings, roads, residential areas, hotels, cinemas, nightclubs and parks sprang up. Apart from being an economic hub, Karachi also became the ‘entertainment capital’ of the country. In 1962 it was dubbed ‘the city of lights.’

On the other hand, the pitfalls of Ayub’s policies were: ethnic tensions between the Mohajir and the new migrants; growing economic gaps between rich and poor; and frustration among the middle-classes for not being able to achieve political influence.

In 1968 Karachi became engulfed by that year’s countrywide protest movement against the Ayub regime.

Population: 6,912,598[21]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; banking; textile; insurance; advertising; hoteling; film.

Language: Urdu was the largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Balochi, Sindhi and English.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority. Punjabis became the second largest ethnic group[22] followed by the Pashtun who arrived in droves from the country’s northern areas as labour.[23] Sindhi and Baloch minorities remained somewhat stable. There were now also many Bengalis from the country’s eastern wing, East Pakistan.

Culture: Cultural activities flourished, especially in the fields of commercial film-making.[24] Dozens of new nightclubs and bars opened and so did new hotels.[25] Urdu theatre grew, even though many of its luminaries joined film, TV and radio. New cinemas emerged catering to a growing film-going audience. The city’s beaches became favourite resorts for locals and tourists alike.

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees continued to be planted along with new flora imported from other countries.

Crime: Karachi had one of the lowest murder rates among the time’s major cities. But pick-pocket gangs still roamed the streets and gangs involved in selling hashish, ‘black cinema tickets,’ and lethal switch-blades emerged.[26] Crimes such as theft, petty-frauds and prostitution were common in congested working-class areas.

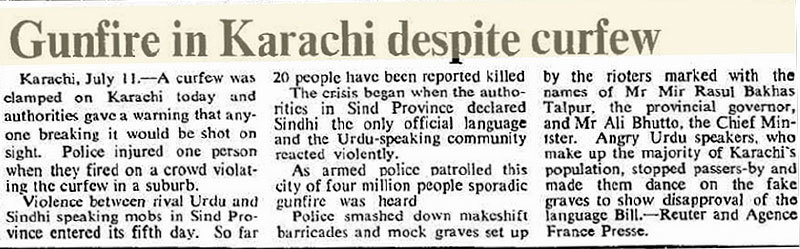

1969-77: A City in Limbo

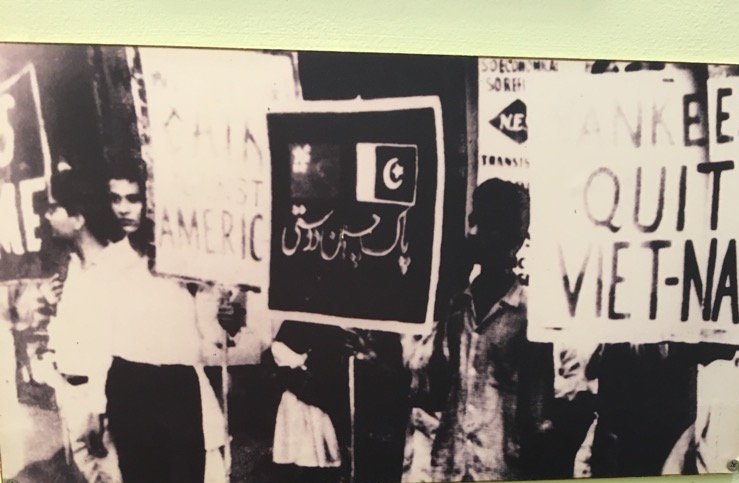

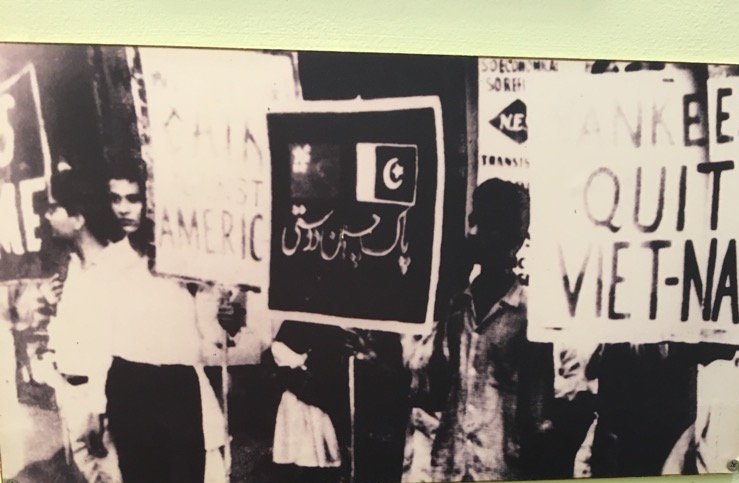

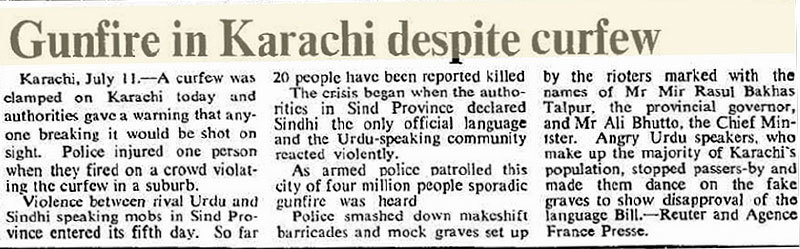

In 1970 Karachi became the capital of Sindh. However, its economic charms began to wither away due to the civil war in East Pakistan and the pounding that Karachi received during the 1971 Pak-India war.

The city also struggled to remain an economic hub when the policies of ZA Bhutto’s left-leaning populist regime triggered a flight of capital and resentment in the trader and business classes.

Karachi’s population continued to grow, though. Encouraged by Bhutto, a large number of Sindhis began settling in Karachi, clashing with the city’s Mohajir majority.[27]

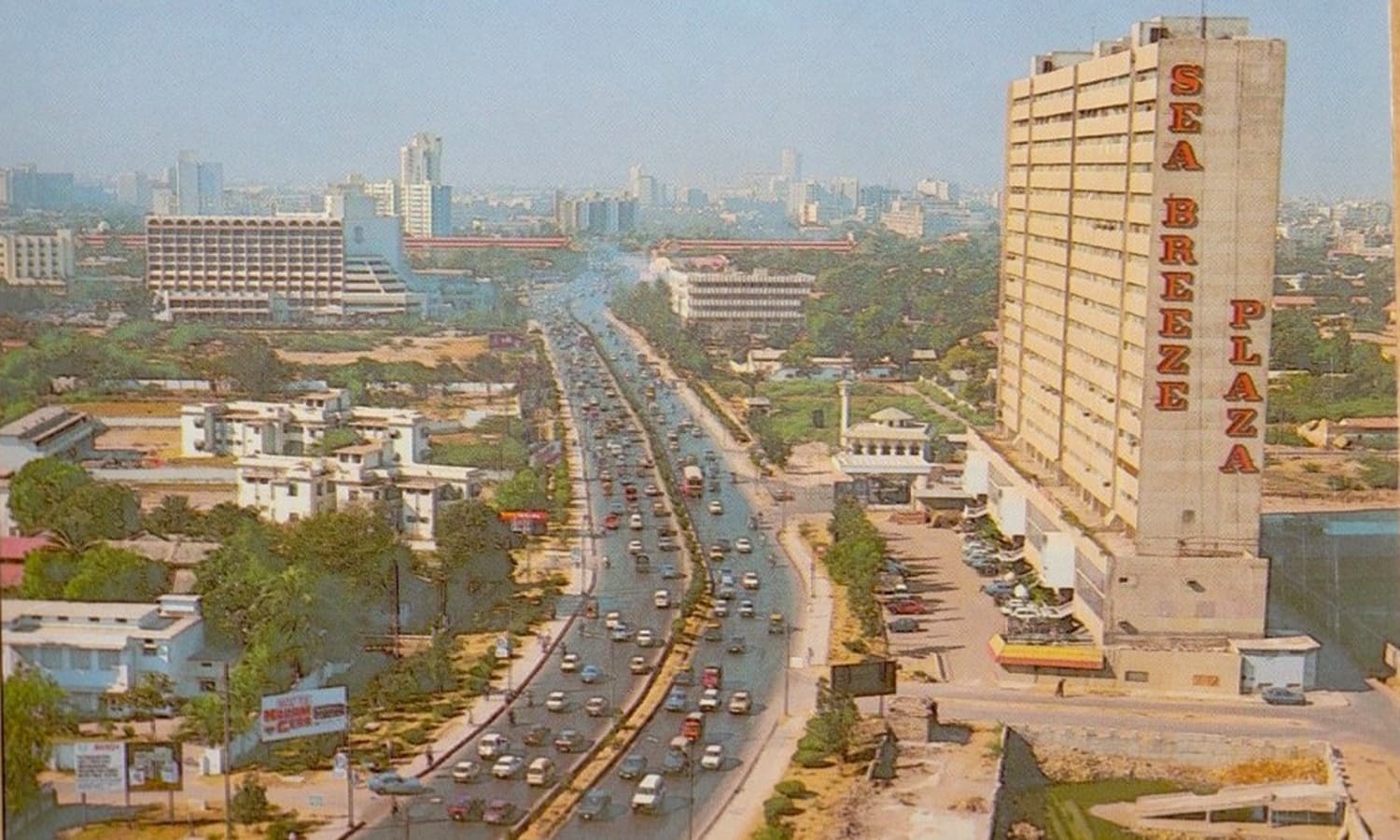

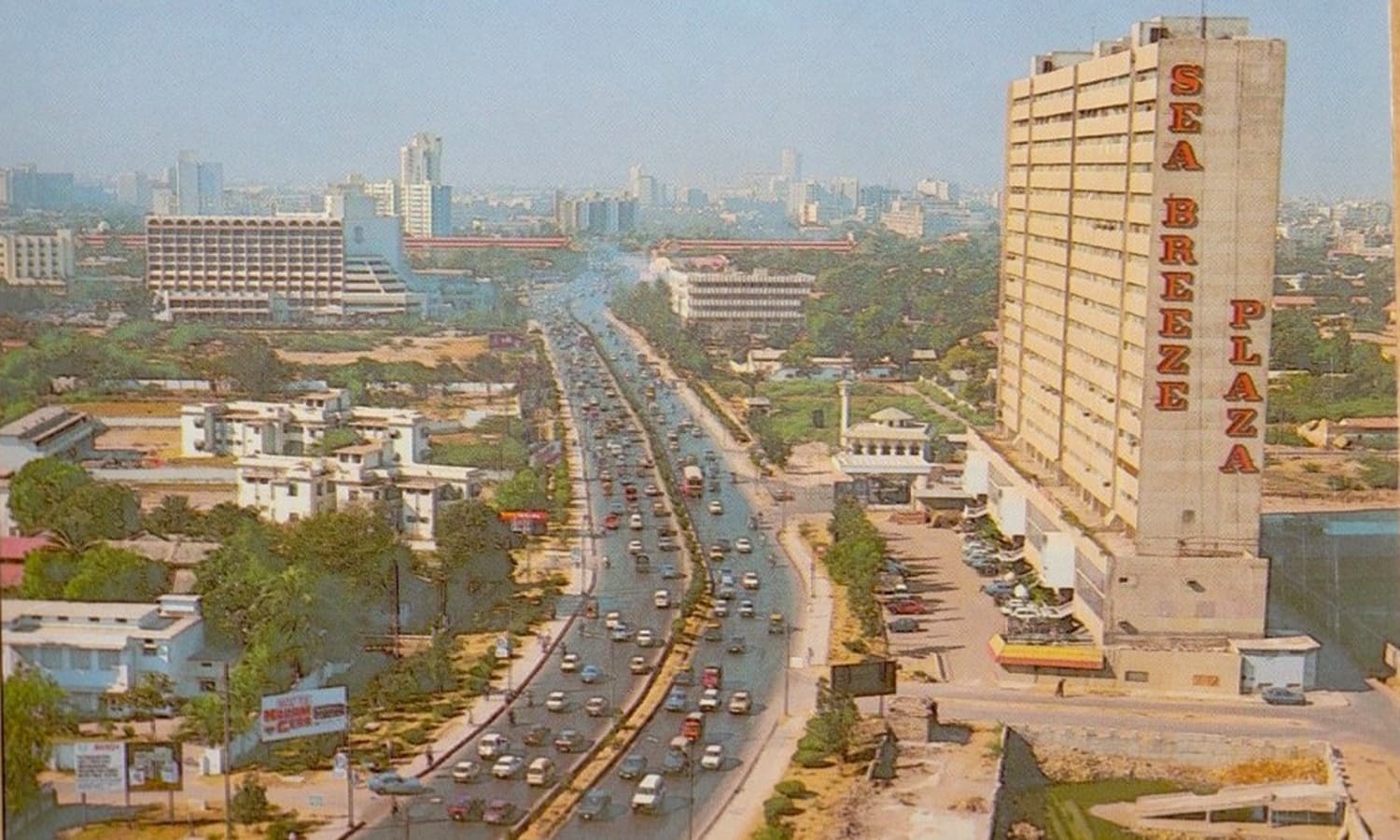

New zoning regulations allowed the building of high-rise apartment blocks.[28] Many of the city’s areas faced degradation due to negligence, and rising population, even though in the mid-1970s the government did launch a ‘beautification of Karachi’ campaign.

In 1977, Karachi became the epicenter of that year’s anti-Bhutto protest movement which led to a reactionary military coup in July 1977.

Population: 10,426,310[29]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; banking; textile; insurance; advertising; hoteling; tourism.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi and English.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group. And even though the number of Sindhis grew, their population was still less than the Pashtun.

Culture: Cultural activities continued to flourish despite the city’s declining economic fortunes. Hotels and bigger cinemas continued to spring up and so did new clubs and bars. Beaches remained a favourite resort, even though they began being commercialized and polluted. ‘Adult’ films were allowed to run in cinemas. A large casino was to start operations in 1977. However, under pressure from the right-wing opposition movement, the casino could not open when the Bhutto regime agreed to ban the sale of alcohol (to Muslims) in April 1977.[30] The ban also saw the closing down of all other bars and nightclubs. There was a manifold growth of TV set owners.

Flora and Fauna: New fauna was introduced during the 1973-74 ‘beautification’ drive.

Crime: Crime grew in the 1970s and so did the rate of murder. But it was still low compared to the world’s other major cities. Gangs of hooligans involved in brawls, extortion and drug peddling were common.

1978-88: Paradox City

After the fall of the Bhutto regime, the Gen Zia dictatorship began to undo the fallen government’s ‘socialist’ policies. Billions of dollars’ worth of aid from the US and Saudi Arabia and the dictatorship’s unabashed ‘pro-business’ initiatives, helped Karachi regain its status as an economic hub.

But the city’s cultural and political disposition changed. An economic boom in the early 1980s triggered a building boom, but one which was paralleled by a large influx of Afghan refugees, many of who came to Karachi carrying weapons and drugs.

Livable land became scarce and the city’s infrastructure came under great duress. Ethnic riots became a norm as ‘land mafias’ pitched one ethnic group against the other.[31] Deadly weapons proliferated and heroin addiction shot up. By 1985, Karachi had the largest number of heroin addicts.

Zia’s policies to promote ‘jihad’ in Afghanistan saw the emergence of radical sectarian groups who occupied Karachi’s mosques and madrassas. Ethnic and sectarian tensions and violence along with a rise in crime in Karachi rather paradoxically rose with the period’s economic growth and physical expansion of Karachi.

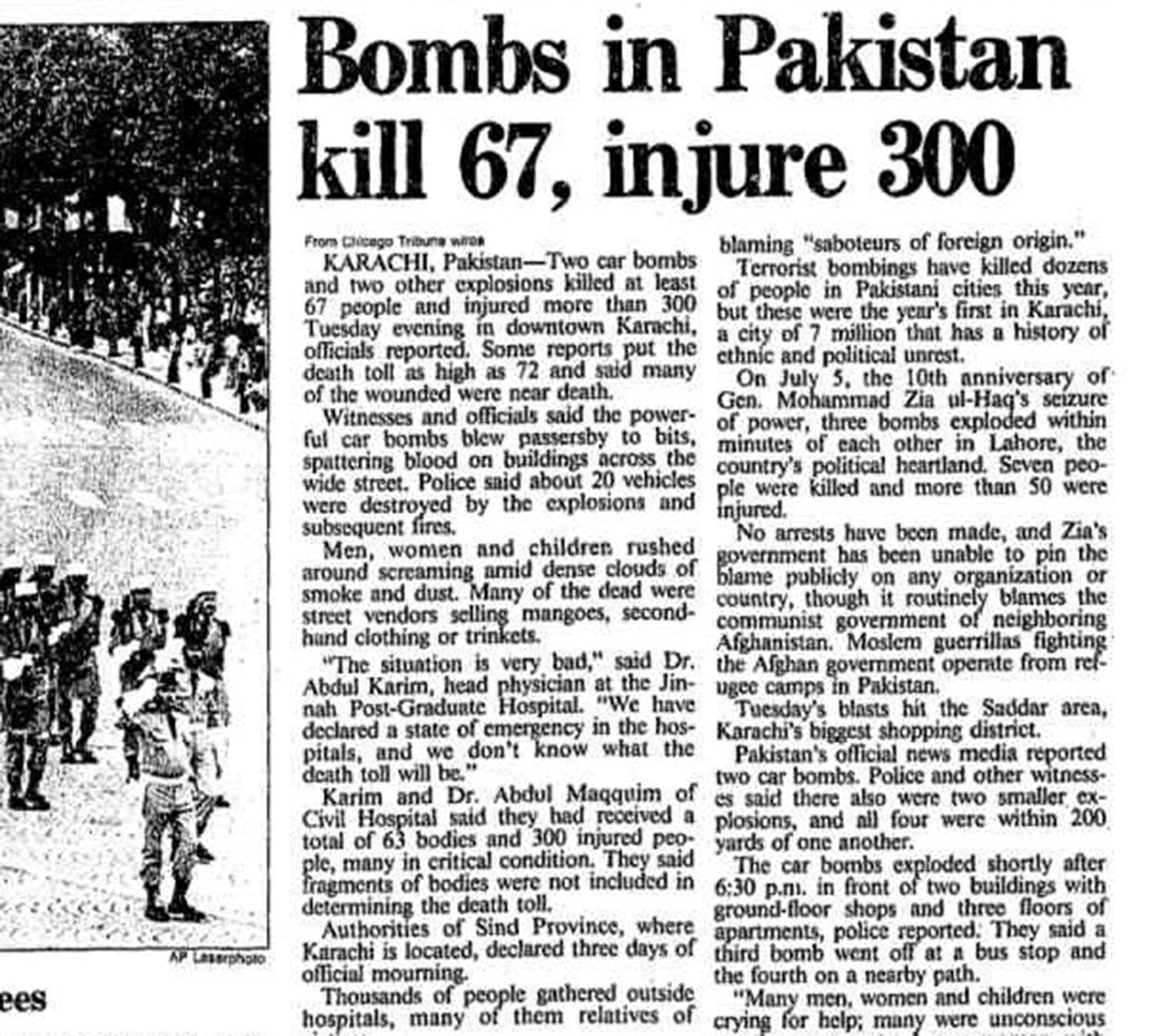

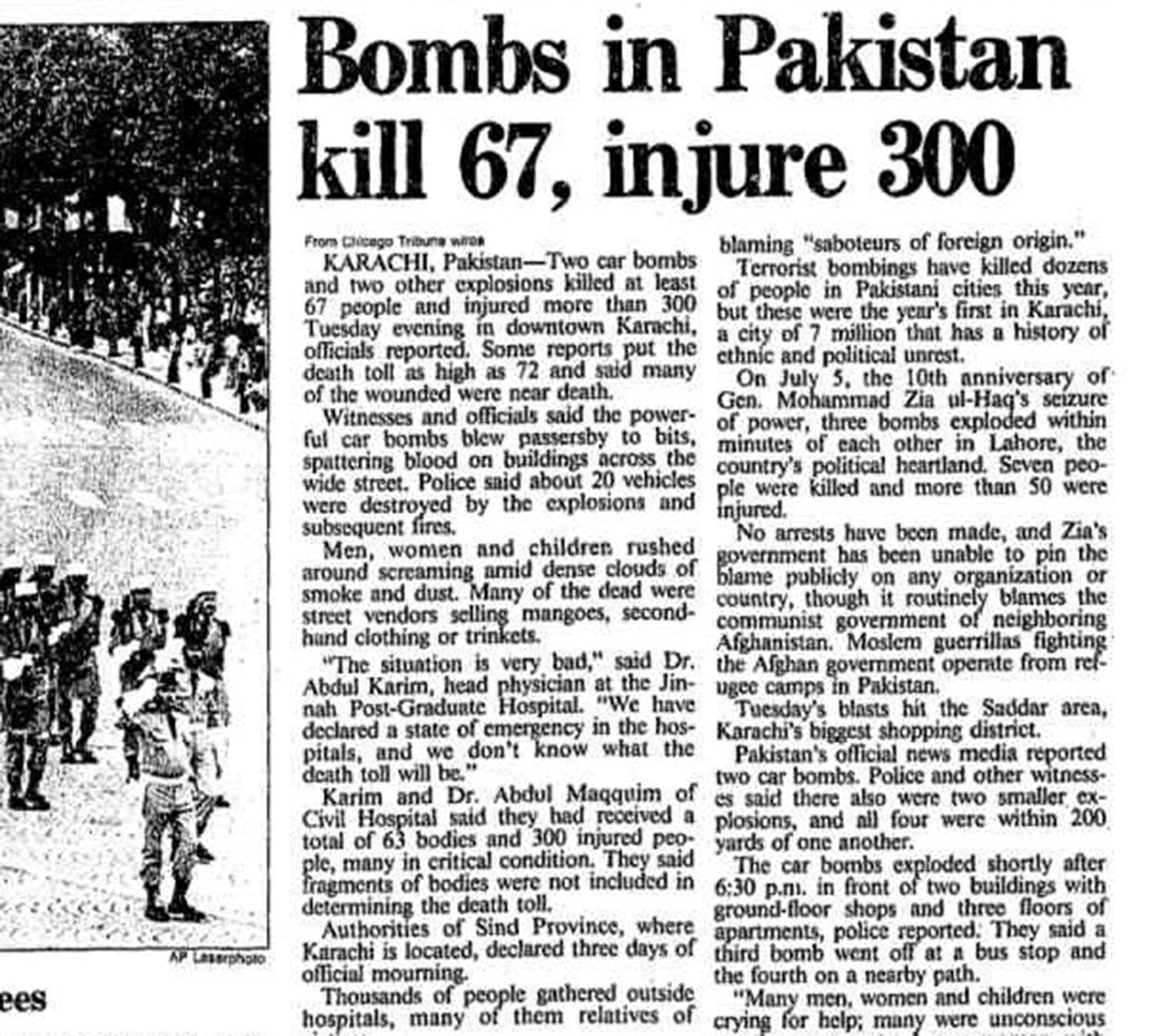

It all came to head when in 1987 Karachi witnessed its very first bomb attack in which 67 Karachittes were killed.

Population: 15,208,132[32]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; advertising.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi and English. Bengali returned with the arrival of Bengali migrants from Bangladesh.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs were in majority, even though this majority fell from over 70% in the 1950s to a little over 50% in 1981. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group, followed by Pashtun, Sindhi and Baloch.

Culture: Due to restrictions, the cinema culture of the city collapsed. With growing consumerism, many cinemas were converted into ‘shopping plazas.’ Homes in Karachi were the first in the country to get VCRs through which friends and families watched smuggled Indian films. Even though the once popular and ‘sophisticated’ Urdu film industry crashed, it was replaced by the popularity of ‘crass’ Punjabi films that found an audience in Karachi. As bars and nightclubs had closed down, everything went inside. Bootleggers did roaring business. Beach resorts were further developed (and further pollution). The curious tradition of celebrating the arrival of the new year with aerial firing began (in 1986). Karachi hosted the international Hockey Champions Trophy in 1980, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1986 and 1988. It held two matches of the 1987 Cricket World Cup.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: The murder rate shot up. Disputes were increasingly settled through the barrel of a gun which became easily available.[33] Property frauds witnessed a spike[34] and heroin peddlers and addicts littered the streets.

1988-99: Things fall apart

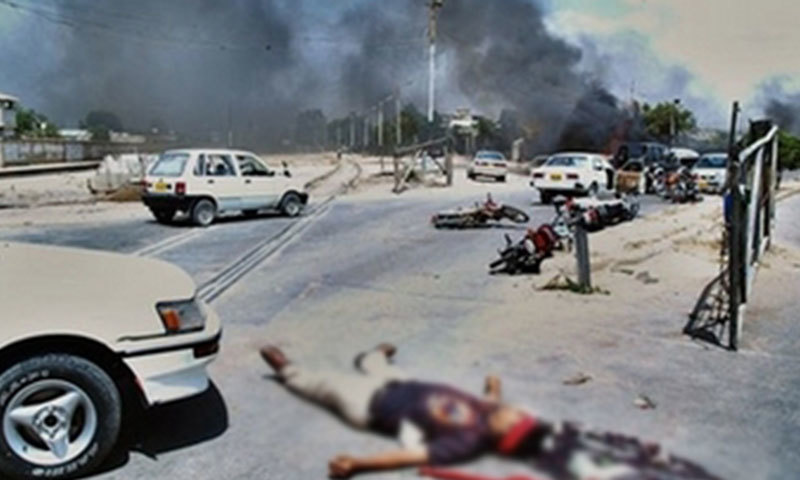

All that had started during the Zia dictatorship, mutated after his death in 1988. Being the country’s economic hub, Karachi was first to be hit by the gradual meltdown of Pakistan’s economy in the 1990s.

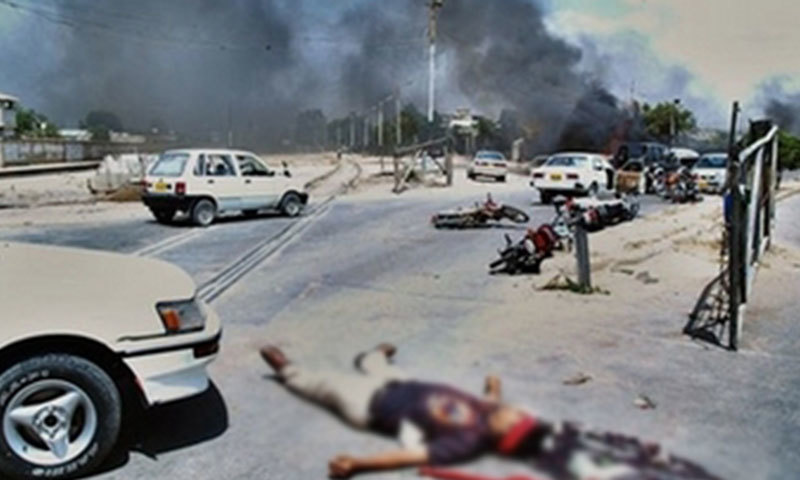

Ethnic and sectarian strife in the city witnessed a manifold growth and the crime rate continued to go up. The city witnessed numerous shutdowns and curfews. Many businesses began to move to Lahore.

Population: 20,269,265[35]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English and Bengali.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs were in majority, but by 1998 this majority fell to 48%. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group, followed by Pashtun, Sindhi and Baloch.

Culture: Cinemas continued to close down. But populist Urdu comedy theatre emerged and thrived. Pop concerts became frequent. Karachi held two games of the 1996 cricket World Cup.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: The murder rate continued to increase. Extortion and kidnapping for ransom grew. Heroin peddling and addiction was still a major issue.

1999-2007: A Brief Respite

After taking over power in 1999, military chief Parvez Musharraf (a Karachiite) released a large financial package for the uplift and restoration of Karachi. Ethnic tensions were reduced as an improving national economy positively impacted Karachi.

Karachi’s economy recovered from the disasters of the previous decade, and a new building boom emerged. However, in 2007, the bubble burst. As the national economy declined, Karachi rudely returned to its old ways. Ethnic violence and crime shot up, as the city dramatically plunged into chaos again.

Population: N/A.

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment; electronic media; IT technology.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, but now closely followed by Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English and Bengali and Burmese.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism, even though the population of Christians and Zoroastrians witnessed a decrease.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority (approx. 41%).[36] Pashtun replaced the Punjabis as the second largest ethnic group in the city.

Culture: Karachi witnessed a new cultural spring of sorts. Urdu films being made in Karachi began their climb; pop concerts and art and fashion shows peaked in 2005. Karachi became the epicenter of the mushrooming private electronic media. Large shopping malls began to come up. Restrictions on licensed liquor stores were relaxed.

Flora and Fauna: The quickly growing Conocarpus plants were introduced (imported from the more tropical regions of the world) to compensate for the negligence that Karachi’s flora had experienced after the 1970s.

Crime: The murder rate was brought under some control but the city became a major target of terrorist attacks committed by extremists linked to Al-Qaeda.

2008-2018: To Hell and Back

Between 2008 and 2015, Karachi struggled to return to normality. Taking advantage of a declining national economy and the widening political schisms, all kind of criminal mafias were able to wreak havoc in the city.

These mafias and gangs exploited the city’s ethnic tensions and were soon joined by members of extremist groups who too began to claim their piece of the pie through murder, extortion and kidnapping.

Things became so bad that the state intervened and launched a widespread operation in the city. A somewhat improvement in the national economy helped restore some peace. But this peace is fragile. It is now to be seen whether the situation has been ‘controlled’ in a more effective manner or has a lid has been put over it like it was in the early 2000s. The lid did not work because at the first sign of a dip in economy, it was blown off.

But the situation between 2015 and 2018 has largely continued to improve.

Population: 14,910,352[37]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment; electronic media; IT technology.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English, Bengali and Burmese.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs are still in majority (but now approx. 40%). Pashtun now make over 23% of the city’s population, followed by Punjabis, Sindhis, Sariki and Baloch.

Culture: From 2010 onwards, Karachi has witnessed a growth in all kind of festivals: food, literature, film and theatre. Multiplexes have revived the cinema-going culture and Karachi is producing the largest number of new Urdu films. Shopping Malls and recreational parks have become popular. The number of legal liquor stores have increased but are still not allowed to sell openly. In 2018, Karachi made it to top 10 list of cities with the highest cannabis consumption.[38] It was placed 2nd after New York.

Flora and Fauna: Conocarpus plants that were introduced in 2003, began to be uprooted after environmental groups pointed out that they were harming the city’s indigenous flora and environment.[39]

Crime: After 2015, the rampaging murder rate was brought down and so was the rate of other heinous crimes. In 2014 Karachi was placed as the 6th most dangerous city by the International Crime Index Rate. However, in 2018, its position dropped to 50! A vast improvement. However, street crimes such as mugging and snatching are still prevalent.

[1] The Ancient Geography of India: A. Cunningham (Cambridge University Press, 2013) p.306

[2] The evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[3] Kitab-ul-Muhit: Sidi A. Ries (16th century).

[4] Naomal Hotchand: Autobiography (19th century)

[5] Ibid.

[6] 1856 British estimate.

[7] Sindh and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus: RS Burton (1851)

[8] Ibid.

[9] Gavan Tredoux: New Light on Richard Burton’s Karachi Brothel Report (2016)

[10] The evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[11] 1891 Karachi Census Report.

[12] The Sindh Gazette (1891)

[13] 1941 Karachi Census Report.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sindh, 1947 and Beyond: P. Kumar, R. Kothari (Journal of South Asian Studies, 2016)

[16] Reports of the Governors of Sindh (1937-47)

[17] 1951 Karachi Census Report.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Khuda Ki Basti: Shaukat Siddique (1957)

[20] Ibid.

[21] 1961 Karachi Census Report.

[22] Ibid

[23] The Evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[24] Explorations into Pakistani Cinema: AN Ahmad (Screen, December 2016).

[25] Instant City: Steve Inskeep (Penguin Books, 2012)

[26] Karachi: Order, Disorder and the Struggle for the City: L. Gayer Oxford University Press, 2012)

[27] Ibid.

[28] The Evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[29] 1972 Karachi Census Report.

[30] Instant City: Steve Inskeep (Penguin Books, 2012)

[31] A Generation Comes of Age: Arif Hasan (Herald, October 1987)

[32] 1981 Karachi Census.

[33] Karachi: Order, Disorder and the Struggle for the City: L. Gayer Oxford University Press, 2012)

[34] The Telegraph (March, 2014).

[35] 1998 Karachi Census.

[36] As the scheduled 2008 census did not take place, this percentage was estimated by various sociologists in 2008.

[37] 2018 Census.

[38] Express Tribune, January 6, 2019.

[39] DAWN May 27, 2018.

If you take a walk in any marketplace in Karachi, there is every likelihood that you would be able to hear five to six different languages. Urdu – rather its many dialects – is the most commonly spoken language here; but Pashtu, Punjabi, Balochi, Gujarati, Sindhi and even English, Bengali and Burmese can also be heard on the city’s streets.

There is also a possibility of you getting mugged. Even while waiting at a traffic signal. That’s Karachi. Mad and bad – and yet extremely diverse and progressive. And it’s big. Very big. It is the world’s sixth most populous city with a population of 14.91 million spread across an area of 3,780 km – and expanding.

326 BC: ‘Krokola’

When Alexander the Great’s armies that had invaded the subcontinent from the Khyber Pass in 327 BC began their exit from the region, they sailed down the River Indus in present-day Pakistan.

Whereas Alexander left for Babylon through a desert along the Makran Coast in Balochistan, one of his admirals, Nearchus, sailed out over the Arabian Sea from the shores of what became Karachi. Nearchus named the place ‘Krokola.’[1]

Population: N/A. But in ancient Greek writings, Krokola at the time had a few fishing villages inhabited by ‘primitive, fish-eating people.’

Economy: N/A.

Language: N/A

Religion: Probably animism.

Ethnicity: N/A.

Culture: Greek texts describe the few inhabitants that they encountered as being ‘primitive.’

Flora and Fauna: N/A. The Greeks only wrote about fish that the few residents caught and ate from the sea.

Crime: N/A.

12th Century CE: ‘Kalachi’

The area is mentioned again in the 12th century literature of Sindh’s Samma dynasty[2] that was based out of Thatta and is approximately 100 km from Karachi. A folk tale during this period spoke of a fisherman who went to ‘Kalachi’ to avenge the deaths of his six brothers who were swallowed by a whale in the sea. While in the sea looking for the whale, the man kills a large crocodile and is received as a hero.

Population: N/A. Probably still sparse and living in small fishing villages.

Economy: N/A.

Language: N/A

Religion: N/A

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi.

Culture: N/A.

Flora and Fauna: In Samma literature ‘Kalachi’ is described as being a sandy and arid area on the shores of a mighty sea. Folklore based in this area speak of whales and crocodiles. This means the seas of Karachi had whales and saltwater crocodiles.

Crime: N/A.

1794 CE: ‘Kolachi Jo Kun’

Even though Arab and Turkish navigators had marked the area as ‘Ras Karashi’ and ‘Kaurashi’[3] on maps in the 15th and 16th centuries, it was still seen as an insignificant backwater location with fishing villages.

In 1794 Sindh’s Talpur dynasty brought the area under its control (from the Kalhora rulers). The location began appearing on maps as a town. The Talpurs fortified it with mud walls and according to texts of the period the town was known as ‘Kolachi Jo Kun’[4] or or Kolachi’s well.

Population: Approximately 5000.[5]

Economy: Based on fishing and some sea trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi.

Religion: Mixed: Largely Hindu with a growing Muslim population.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi; Some Baloch.

Culture: N/A.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: Later British records talk about brothels, opium dens and gambling houses.

1839-57 CE: ‘Kowrachee Town’.

In 1839, armies of the British East India Company defeated the Talpurs and conquered Karachi. They called it ‘Kowrachee Town’ and/or ‘Kuraachee.’

The British began to develop Karachi’s port and introduced local governance overseen by British officials. A policing system was also introduced and modern methods of taxation. In 1858, the British East India Company was abolished and Karachi, like the rest of India, became part of the British Crown.

Population: 56,875.[6]

Economy: Based on fishing and sea trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi and some Balochi dialects. The British introduced English.

Religion: Largely Hindu and Muslim.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi; Some Baloch.

Culture: British writings of the period describe a lively but ‘filthy’ town of about fifty thousand people.[7] The same writings explained the men of this town as being ‘hard working but boisterous’ and the women as ‘loud but fond of wearing bright coloured clothes.’[8] The men loved to fight, gamble and drink. Most were fishermen.

Flora and Fauna: British texts mention eagles (kites), crows, pigeons, seagulls and parrots as the main birds. Dogs, cats, foxes, wolves, swine, snakes, crocodiles, camels, scorpions and all kind of fish are also mentioned. The land was mostly rough, sandy and covered with shrubs and mangroves. Palm trees were common.

Crime: British records mention brothels, opium dens and gambling houses.[9] Murder was rare but brawls between men were common.

1860-1900: Karachi

The British began initiating various infrastructural projects. With the development of the port, sea trade grew rapidly, attracting migrants from the rest of India. Railway lines were laid and the tramway introduced.

By 1870 Karachi had become the largest exporter of wheat and cotton to the rest of India.[10] In the 1890s, however, a bubonic plague killed hundreds of locals. As a consequence, the British began constructing an elaborate sewage and garbage collection system.

Population: 105,199[11]

Economy: Based on fishing and sea and land trade.

Language: Largely Sindhi and Balochi. English was increasingly used in official documents. Hindi too began to be spoken.

Religion: Hinduism followed by Islam. Christianity began to emerge as well.

Ethnicity: Largely Sindhi and Baloch. Indian Hindi-speakers and British English-speakers increased.

Culture: Pluralistic. Gambling and opium dens were closed and replaced with ‘posh’ clubs (for the British and the rich). Local drinking joints were replaced with pubs. Parks and theatres were constructed along with a cinema (Star Cinema). Hindu and Muslim religious festivals were tolerated. Christmas day was declared a holiday as well. Churches were built here for the first time.[12]

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees were most common. But the British also introduced some new flora brought from elsewhere in India. Eagles, crows, sparrows, seagulls, parrots and pigeons still ruled the skies. Cats, dogs, foxes, wolves, swine, cow, goats and camels walked the land. Number of horses increased. Texts of the period also speak of leopards and panthers attacking cattle in the less populated areas of Karachi. Whale, turtle, shark and dolphin sightings were frequent.

Crime: Compared to other cities of India, crime at the time in Karachi was low. Murder was rare, but cases of theft, inflicting physical injury and drunkard brawls increased.

1901-1946: ‘Paris of the East’

Karachi quickly emerged as an important economic hub of British India. Electricity was introduced and the economic boom attracted even more migrants. The British declared Karachi India’s most peaceful city. Some dubbed it the ‘Paris of the East.’

New residential areas, commercial buildings and roads (to now accommodate cars) were made and a strong local government system allowed Karachiites to elect their own mayor. However, the city’s older areas became congested with the arrival of migrant labour.

The first ever airport in India was built in Karachi.

Population: 435,887[13]

Economy: Fisheries; sea/air/land trade; banking; Insurance.

Language: Largely Sindhi and Balochi. English, Urdu, Gujarati and Hindi too became increasingly common.[14]

Religion: Hinduism (51%) and Islam (42%). Christianity (3.5%). Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Jain and Jewish communities constituted 5% of the population.

Ethnicity: Sindhi followed by Baloch, Hindi-speakers, Urdu-speakers, Punjabi, Memon, Goan and British.

Culture: Pluralistic. Texts of the period speak of ‘sound work ethics of Karachiites’. Number of parks, theaters, cinemas, beach-side resorts, pubs/bars, clubs, schools and collages increased. Karachi was least impacted by the ‘communal’ animosities between Hindu and Muslims present elsewhere in India.[15]

Flora and Fauna: New flora was introduced in parks and the Karachi Zoo. But palm trees remained a favourite. Population of leopards/panthers in the outskirts began to decline. So did the population of foxes and wolves.

Crime: Overall rate of crime remained low in Karachi compared to other major cities of India.[16] The policing system was good. However, crimes such as theft, brawling and petty-frauds were common in the more congested working-class areas.

1947-57: A City Turned On Its Head

Ironically, Hindus were in a majority in Karachi when in August 1947 the city became part of the newly-formed Pakistan. In 1948 Karachi was named Pakistan’s capital. By 1951, as the large influx of Urdu-speaking refugees from India (Mohajir) continued, and most of them began settling in Karachi, the Hindus began moving the other way and migrated to India.

Within a span of just three years, Karachi had a new majority: the Mohajir.

The city’s infrastructure was severely tested by the sudden growth of population and when thousands of Mohajirs who could not find a home, were settled in congested refugee camps.

This often caused tensions between the state and the new settlers in the shape of student riots. The city gradually began to lose its sheen.

Population: 1,068,459[17]

Economy: Fisheries; sea/land/air trade; banking.

Language: Urdu replaced Sindhi as the most spoken language of Karachi.[18] Sindhi-speakers declined. Punjabi-speakers increased, arriving from Punjab. Other languages spoken here were Balochi, Guajarati and English.

Religion: Islam became the majority religion. Christians, Zoroastrians, Hindus and Jews constituted about 6% of the city’s population.

Ethnicity: Mohajir majority, followed by Punjabi, Sindhi and Baloch minorities.

Culture: Since most Mohajirs arriving from various Indian cities were inherently cosmopolitan, Karachi retained its pluralistic character. Much of the literature and cinema emerging from the city during this period focused on the problems being faced by the Mohajir squatting in congested refugee camps. Since Karachi was the country’s capital and thus the most visited city of Pakistan, 5-star hotels and new cinemas began being built.

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees remained to be omnipresent and some new flora was introduced along roadsides and in parks. Population of eagles, sparrows, crows, pigeons, stray dogs and cats increased. The foxes and wolves vanished.

Crime: The crime rate shot up. It was most rampant in and around refugee camps.[19] The murder rate was still low, but pick-pocket gangs carrying blades and knives became ubiquitous.[20] Cases of corruption too increased.

1958-68: ‘City of Lights’

A year after army chief Ayub Khan took over power through a military coup in 1958, Karachi lost its status as the capital of Pakistan. But the city did become the epicenter of the regime’s robust industrialization policies.

Economic activity in the city advanced at a rapid pace, attracting new migrants and reviving the city’s historic reputation as being an economic hub. New commercial buildings, roads, residential areas, hotels, cinemas, nightclubs and parks sprang up. Apart from being an economic hub, Karachi also became the ‘entertainment capital’ of the country. In 1962 it was dubbed ‘the city of lights.’

On the other hand, the pitfalls of Ayub’s policies were: ethnic tensions between the Mohajir and the new migrants; growing economic gaps between rich and poor; and frustration among the middle-classes for not being able to achieve political influence.

In 1968 Karachi became engulfed by that year’s countrywide protest movement against the Ayub regime.

Population: 6,912,598[21]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; banking; textile; insurance; advertising; hoteling; film.

Language: Urdu was the largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Balochi, Sindhi and English.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority. Punjabis became the second largest ethnic group[22] followed by the Pashtun who arrived in droves from the country’s northern areas as labour.[23] Sindhi and Baloch minorities remained somewhat stable. There were now also many Bengalis from the country’s eastern wing, East Pakistan.

Culture: Cultural activities flourished, especially in the fields of commercial film-making.[24] Dozens of new nightclubs and bars opened and so did new hotels.[25] Urdu theatre grew, even though many of its luminaries joined film, TV and radio. New cinemas emerged catering to a growing film-going audience. The city’s beaches became favourite resorts for locals and tourists alike.

Flora and Fauna: Palm trees continued to be planted along with new flora imported from other countries.

Crime: Karachi had one of the lowest murder rates among the time’s major cities. But pick-pocket gangs still roamed the streets and gangs involved in selling hashish, ‘black cinema tickets,’ and lethal switch-blades emerged.[26] Crimes such as theft, petty-frauds and prostitution were common in congested working-class areas.

1969-77: A City in Limbo

In 1970 Karachi became the capital of Sindh. However, its economic charms began to wither away due to the civil war in East Pakistan and the pounding that Karachi received during the 1971 Pak-India war.

The city also struggled to remain an economic hub when the policies of ZA Bhutto’s left-leaning populist regime triggered a flight of capital and resentment in the trader and business classes.

Karachi’s population continued to grow, though. Encouraged by Bhutto, a large number of Sindhis began settling in Karachi, clashing with the city’s Mohajir majority.[27]

New zoning regulations allowed the building of high-rise apartment blocks.[28] Many of the city’s areas faced degradation due to negligence, and rising population, even though in the mid-1970s the government did launch a ‘beautification of Karachi’ campaign.

In 1977, Karachi became the epicenter of that year’s anti-Bhutto protest movement which led to a reactionary military coup in July 1977.

Population: 10,426,310[29]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; banking; textile; insurance; advertising; hoteling; tourism.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi and English.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group. And even though the number of Sindhis grew, their population was still less than the Pashtun.

Culture: Cultural activities continued to flourish despite the city’s declining economic fortunes. Hotels and bigger cinemas continued to spring up and so did new clubs and bars. Beaches remained a favourite resort, even though they began being commercialized and polluted. ‘Adult’ films were allowed to run in cinemas. A large casino was to start operations in 1977. However, under pressure from the right-wing opposition movement, the casino could not open when the Bhutto regime agreed to ban the sale of alcohol (to Muslims) in April 1977.[30] The ban also saw the closing down of all other bars and nightclubs. There was a manifold growth of TV set owners.

Flora and Fauna: New fauna was introduced during the 1973-74 ‘beautification’ drive.

Crime: Crime grew in the 1970s and so did the rate of murder. But it was still low compared to the world’s other major cities. Gangs of hooligans involved in brawls, extortion and drug peddling were common.

1978-88: Paradox City

After the fall of the Bhutto regime, the Gen Zia dictatorship began to undo the fallen government’s ‘socialist’ policies. Billions of dollars’ worth of aid from the US and Saudi Arabia and the dictatorship’s unabashed ‘pro-business’ initiatives, helped Karachi regain its status as an economic hub.

But the city’s cultural and political disposition changed. An economic boom in the early 1980s triggered a building boom, but one which was paralleled by a large influx of Afghan refugees, many of who came to Karachi carrying weapons and drugs.

Livable land became scarce and the city’s infrastructure came under great duress. Ethnic riots became a norm as ‘land mafias’ pitched one ethnic group against the other.[31] Deadly weapons proliferated and heroin addiction shot up. By 1985, Karachi had the largest number of heroin addicts.

Zia’s policies to promote ‘jihad’ in Afghanistan saw the emergence of radical sectarian groups who occupied Karachi’s mosques and madrassas. Ethnic and sectarian tensions and violence along with a rise in crime in Karachi rather paradoxically rose with the period’s economic growth and physical expansion of Karachi.

It all came to head when in 1987 Karachi witnessed its very first bomb attack in which 67 Karachittes were killed.

Population: 15,208,132[32]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; advertising.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi and English. Bengali returned with the arrival of Bengali migrants from Bangladesh.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs were in majority, even though this majority fell from over 70% in the 1950s to a little over 50% in 1981. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group, followed by Pashtun, Sindhi and Baloch.

Culture: Due to restrictions, the cinema culture of the city collapsed. With growing consumerism, many cinemas were converted into ‘shopping plazas.’ Homes in Karachi were the first in the country to get VCRs through which friends and families watched smuggled Indian films. Even though the once popular and ‘sophisticated’ Urdu film industry crashed, it was replaced by the popularity of ‘crass’ Punjabi films that found an audience in Karachi. As bars and nightclubs had closed down, everything went inside. Bootleggers did roaring business. Beach resorts were further developed (and further pollution). The curious tradition of celebrating the arrival of the new year with aerial firing began (in 1986). Karachi hosted the international Hockey Champions Trophy in 1980, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1986 and 1988. It held two matches of the 1987 Cricket World Cup.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: The murder rate shot up. Disputes were increasingly settled through the barrel of a gun which became easily available.[33] Property frauds witnessed a spike[34] and heroin peddlers and addicts littered the streets.

1988-99: Things fall apart

All that had started during the Zia dictatorship, mutated after his death in 1988. Being the country’s economic hub, Karachi was first to be hit by the gradual meltdown of Pakistan’s economy in the 1990s.

Ethnic and sectarian strife in the city witnessed a manifold growth and the crime rate continued to go up. The city witnessed numerous shutdowns and curfews. Many businesses began to move to Lahore.

Population: 20,269,265[35]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Punjabi, Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English and Bengali.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs were in majority, but by 1998 this majority fell to 48%. Punjabis were the second largest ethnic group, followed by Pashtun, Sindhi and Baloch.

Culture: Cinemas continued to close down. But populist Urdu comedy theatre emerged and thrived. Pop concerts became frequent. Karachi held two games of the 1996 cricket World Cup.

Flora and Fauna: N/A.

Crime: The murder rate continued to increase. Extortion and kidnapping for ransom grew. Heroin peddling and addiction was still a major issue.

1999-2007: A Brief Respite

After taking over power in 1999, military chief Parvez Musharraf (a Karachiite) released a large financial package for the uplift and restoration of Karachi. Ethnic tensions were reduced as an improving national economy positively impacted Karachi.

Karachi’s economy recovered from the disasters of the previous decade, and a new building boom emerged. However, in 2007, the bubble burst. As the national economy declined, Karachi rudely returned to its old ways. Ethnic violence and crime shot up, as the city dramatically plunged into chaos again.

Population: N/A.

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment; electronic media; IT technology.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, but now closely followed by Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English and Bengali and Burmese.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism, even though the population of Christians and Zoroastrians witnessed a decrease.

Ethnicity: Mohajir were in majority (approx. 41%).[36] Pashtun replaced the Punjabis as the second largest ethnic group in the city.

Culture: Karachi witnessed a new cultural spring of sorts. Urdu films being made in Karachi began their climb; pop concerts and art and fashion shows peaked in 2005. Karachi became the epicenter of the mushrooming private electronic media. Large shopping malls began to come up. Restrictions on licensed liquor stores were relaxed.

Flora and Fauna: The quickly growing Conocarpus plants were introduced (imported from the more tropical regions of the world) to compensate for the negligence that Karachi’s flora had experienced after the 1970s.

Crime: The murder rate was brought under some control but the city became a major target of terrorist attacks committed by extremists linked to Al-Qaeda.

2008-2018: To Hell and Back

Between 2008 and 2015, Karachi struggled to return to normality. Taking advantage of a declining national economy and the widening political schisms, all kind of criminal mafias were able to wreak havoc in the city.

These mafias and gangs exploited the city’s ethnic tensions and were soon joined by members of extremist groups who too began to claim their piece of the pie through murder, extortion and kidnapping.

Things became so bad that the state intervened and launched a widespread operation in the city. A somewhat improvement in the national economy helped restore some peace. But this peace is fragile. It is now to be seen whether the situation has been ‘controlled’ in a more effective manner or has a lid has been put over it like it was in the early 2000s. The lid did not work because at the first sign of a dip in economy, it was blown off.

But the situation between 2015 and 2018 has largely continued to improve.

Population: 14,910,352[37]

Economy: Sea/air/land trade; fisheries; transport; property; banking; textile; insurance; entertainment; electronic media; IT technology.

Language: Urdu largest spoken language, followed by Pashtu, Gujarati, Sindhi, Balochi, English, Bengali and Burmese.

Religion: Islam. Followed by Christianity, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Ethnicity: Mohajirs are still in majority (but now approx. 40%). Pashtun now make over 23% of the city’s population, followed by Punjabis, Sindhis, Sariki and Baloch.

Culture: From 2010 onwards, Karachi has witnessed a growth in all kind of festivals: food, literature, film and theatre. Multiplexes have revived the cinema-going culture and Karachi is producing the largest number of new Urdu films. Shopping Malls and recreational parks have become popular. The number of legal liquor stores have increased but are still not allowed to sell openly. In 2018, Karachi made it to top 10 list of cities with the highest cannabis consumption.[38] It was placed 2nd after New York.

Flora and Fauna: Conocarpus plants that were introduced in 2003, began to be uprooted after environmental groups pointed out that they were harming the city’s indigenous flora and environment.[39]

Crime: After 2015, the rampaging murder rate was brought down and so was the rate of other heinous crimes. In 2014 Karachi was placed as the 6th most dangerous city by the International Crime Index Rate. However, in 2018, its position dropped to 50! A vast improvement. However, street crimes such as mugging and snatching are still prevalent.

[1] The Ancient Geography of India: A. Cunningham (Cambridge University Press, 2013) p.306

[2] The evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[3] Kitab-ul-Muhit: Sidi A. Ries (16th century).

[4] Naomal Hotchand: Autobiography (19th century)

[5] Ibid.

[6] 1856 British estimate.

[7] Sindh and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus: RS Burton (1851)

[8] Ibid.

[9] Gavan Tredoux: New Light on Richard Burton’s Karachi Brothel Report (2016)

[10] The evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[11] 1891 Karachi Census Report.

[12] The Sindh Gazette (1891)

[13] 1941 Karachi Census Report.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sindh, 1947 and Beyond: P. Kumar, R. Kothari (Journal of South Asian Studies, 2016)

[16] Reports of the Governors of Sindh (1937-47)

[17] 1951 Karachi Census Report.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Khuda Ki Basti: Shaukat Siddique (1957)

[20] Ibid.

[21] 1961 Karachi Census Report.

[22] Ibid

[23] The Evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[24] Explorations into Pakistani Cinema: AN Ahmad (Screen, December 2016).

[25] Instant City: Steve Inskeep (Penguin Books, 2012)

[26] Karachi: Order, Disorder and the Struggle for the City: L. Gayer Oxford University Press, 2012)

[27] Ibid.

[28] The Evolution of Karachi: Arif Hasan (2009)

[29] 1972 Karachi Census Report.

[30] Instant City: Steve Inskeep (Penguin Books, 2012)

[31] A Generation Comes of Age: Arif Hasan (Herald, October 1987)

[32] 1981 Karachi Census.

[33] Karachi: Order, Disorder and the Struggle for the City: L. Gayer Oxford University Press, 2012)

[34] The Telegraph (March, 2014).

[35] 1998 Karachi Census.

[36] As the scheduled 2008 census did not take place, this percentage was estimated by various sociologists in 2008.

[37] 2018 Census.

[38] Express Tribune, January 6, 2019.

[39] DAWN May 27, 2018.