I spent many years travelling throughout Pakistan as a personal assistant for my sadly demised husband Dr Adam Nayyar assisting him in his field work as an anthropologist and, specially, as an ethnomusicologist. Now, from my forlorn retirement in a small Balearic island where nothing happens but the winter sea storms, I cannot help to keep on musing, facing the waves, about Pakistan, a home country I discovered late in life and I cannot help but returning over and over to its inspiring citizens as food for thought and for the soul-searching soul.

I learned many lessons thanks to Pakistanis, from all walks of life, nevertheless, thanks to my husband´s profession I was able to receive particularly deep and touching lessons from Pakistan´s simple folk persons that city dwellers often disregard for being “illiterate” and “backward”.

Alright, maybe they cannot read and write, but there are other skills that apply to conducting a life, different kinds of knowledge, free and unbound from the fetters of written and linear discourse and, mind you, there are other dimensions of being far from logic and from the “scientifically proven” slogan that pesters modern literate life.

There is a lot to be borrowed from those that we carelessly call “simple minds”. There is a lot I learned and earned thanks to them, and there is also a sizeable inner wealth that I owe to them; this letter is about gratitude; about my thankfulness for their opening new avenues in my discourse and for clearing lost ones, blocked by the rubble of time and age.

Our home in Islamabad used to be a hub for anthropologists, geographers and above all, ethnomusicologists from all over the world, and one cold month of December, here they were, the Sakatas, who were an affable couple of Japanese-American ethnomusicologists, specialised in South Asian music (particularly Pashto and Afghan) in their annual tour of the subcontinent.

They had heard some interesting and reliable singers, and also some even more reliable malangs, speak of the shrine of Lahut Lamakan, close to the frontier between Sindh and Balochistan. They had been told not to miss it and Mme Sakata knew that my husband, her faithful colleague, could not fail to orchestrate a visit to that dreamland, famous among Afghan connoisseurs of the real thing, as far as Sufi itineraries are concerned.

Soon were we flying to Karachi airport, where dear Abdul Chang from Jamshoro University, a disciple of Adam´s, was waiting for us with a small van and a warm Sindhi smile, and off we went for hours and hours of frighteningly dusty roads and trails.

Late at night we arrived to our village; there we were told that the shrine we were looking for was “not very far away” further in the hills. Finally we reached a diminutive and pitch dark hamlet, pervaded by the sound of a quiet, yes quiet, drum, whose dim beat was sustaining the dance of the last believer in trance of the day.

In Pakistan, everybody seems to be aware – at least in the musical circuit – that a dancer who is undergoing a trance and “has lost control” has to be left alone and allowed to come back to his senses smoothly with the help of the diminishing rhythm of a respectful drum, lest he dies or gets in deep health trouble.

Actually, everybody would accuse a drummer of murder if he stopped beating his tabla or his dhol, before the person in trance “comes back”. Other adepts will take over, when the drummer has almost reached silence, to help with the “landing operation”, stroking the dancer and holding his hands, talking to him softly until he becomes himself again, safely grounded.

We shared the shrine´s flagging lamp and its cuisine with the drummer and we spent the night in an ample open shed for pilgrims, too tired to worry about the mosquitoes which managed to infect some of us with malaria. The next morning we enjoyed memorably warm nan and tea, not far from a little cemetery decorated with waving colourful rags, Buddhist style, flags and banners of the many cultures that this land has known and made meet.

And then we set for yet another expedition towards “the cave”. We had been informed at the shrine that our trip would be pointless if we did not enter “the cave”. The van dropped us at the beginning of the “holy trail” which through boulders and ravines led up to the cavern. After some time of steep climbing, we saw that there were pieces of rope tied to rocks and hanging trees, to help and guide the climbers but Mr and Mrs Sakata soon had to acknowledge that their health was not up to the mark and that they could not go on. Nevertheless they encouraged us to pursue, and said they would wait there, as long as necessary for our return and for our report.

On our way up we found a few other pilgrims, and several women with babies in their arms. Some of them were quite aged; grandmothers, worried for the health of their grandsons and granddaughters, who, unlike the old ladies I see around me, in the “literate” world, had iron legs, the elasticity of teenagers and showed a flabbergasting intrepidity with their tender load. Obviously, the healthy diet and the lack of cars and elevators in their lives had something to do with their endurance, but more than anything I think, it was the hope of seeing their little ones blessed or cured which gave them that extraordinary stamina, although there is an important factor to reckon with: the approach, the attitude of their society towards them: they are not pitied for being old, but respected and listened to; never stopped from action “due to their age”, free from “anti-aging “ concerns and quackeries, growing in power and responsibility as long and as much as nature admits.

Finally we attained the magic spot. There was a rope ladder to climb in order to get to the entrance of the dark grotto. A kind pilgrim, sticking to the touching solidarity we had noticed throughout our climb, held the foot of the ladder for us, and after some trembling and fearsome steps, there we were!

After a few initial minutes of blindness, I could only discern a small candle wavering on top of a kind of rocky altar in the background ,with a woman kneeling in front of it with her small child. Suddenly, a gentleman pulled my sleeve and with a smile I will never forget, he pointed to a corner to the right and murmured with bright eyes as of a child, “Here you have Noah´s Ark” floating on a small pond of water which dropped from the ceiling, was travelling some kind of stone shape which vaguely resembled a boat ,with a candle where the would-be mast would have been.

The grotto had many “apartments” and recesses, each with a name I began to realise, and with a small candle in front of which each pilgrim could choose to pray and/or pay his respects. With time my eyesight had become used to the twilight – and conditioned by the “spirit of the place” – and everything seemed more and more suggestive and wondrous.

It made me think of my childhood, when with my brothers, sisters and friends we would play and “explore” caves in the depths of the Old Castilian province of Avila, finding names to baptise each nook and corner of the caverns with the titles that our short repertoire of readings and our limited memory for awesome words could allow for, creating a real wonderland, such as this one in Lahut Lamakan.

Only the dwellers and baptizers here, in twenty first century Pakistan, were not children but adults, with the eyes, the strength ,and the Vis Poetica of children. I could have stayed there for ever.

But we had to go. Adam was adamant. I do not remember the way back, so engrossed was I with my stay in this fairy tale place where we were all full-fledged human beings, enjoying the power of both maturity and youth until we reached, on our way downwards, a gap that had to be jumped down and across by way of negotiation. Thank God Mr Sakata was there to counter the ten feet free fall with a smile and his strong arms. I wonder how did the pilgrim ladies manage on this stretch, with their babies and all.

Back in the village Mr and Mrs Sakata and Adam are interviewing and recording musicians, dancers and malangs around the fire, while I curl close to its heat, trying to recall what I felt this morning at the cave. A father makes his little son in his lap watch, with a majestic arm gesture out of his shawl, the beautiful dance of sparks and ashes flying like butterflies frightened by the crackling of the wood logs. The boy enraptured points at some fluttering entities.

It makes me sad to think that most probably, I will never be able to come back to the cave of Lahut Lamakan. And I am taken aback by the fear that the resurrection of my child´s eyes, and their devoted, and courageous gaze which I was able to share with other adults, just as deprived of shame and free from commonsensical logic as I was, remains there, in the cavern.

Never again the needful conjunction of persons and factors required to return will take place. Even though it is the most necessary shrine I have seen in Pakistan, the one I miss the most and the one that floods with melancholy my western life, missing “no end” as Adam would say, Pakistan, and its openings to the unknown and nevertheless felt, with its constant breakthroughs in the yet so wise realm of the “not scientifically proven” .

Lahut Lamakan is not only about trance and folklore, it happens to be “in charge” of quite a few sidelined truths of which it bears, generously, the full burden of proof. A true philosophical truce, for sooth!

May it live long and may it enlighten many an inner path for pilgrims to come.

I learned many lessons thanks to Pakistanis, from all walks of life, nevertheless, thanks to my husband´s profession I was able to receive particularly deep and touching lessons from Pakistan´s simple folk persons that city dwellers often disregard for being “illiterate” and “backward”.

Alright, maybe they cannot read and write, but there are other skills that apply to conducting a life, different kinds of knowledge, free and unbound from the fetters of written and linear discourse and, mind you, there are other dimensions of being far from logic and from the “scientifically proven” slogan that pesters modern literate life.

There is a lot to be borrowed from those that we carelessly call “simple minds”. There is a lot I learned and earned thanks to them, and there is also a sizeable inner wealth that I owe to them; this letter is about gratitude; about my thankfulness for their opening new avenues in my discourse and for clearing lost ones, blocked by the rubble of time and age.

Our home in Islamabad used to be a hub for anthropologists, geographers and above all, ethnomusicologists from all over the world, and one cold month of December, here they were, the Sakatas, who were an affable couple of Japanese-American ethnomusicologists, specialised in South Asian music (particularly Pashto and Afghan) in their annual tour of the subcontinent.

They had heard some interesting and reliable singers, and also some even more reliable malangs, speak of the shrine of Lahut Lamakan, close to the frontier between Sindh and Balochistan. They had been told not to miss it and Mme Sakata knew that my husband, her faithful colleague, could not fail to orchestrate a visit to that dreamland, famous among Afghan connoisseurs of the real thing, as far as Sufi itineraries are concerned.

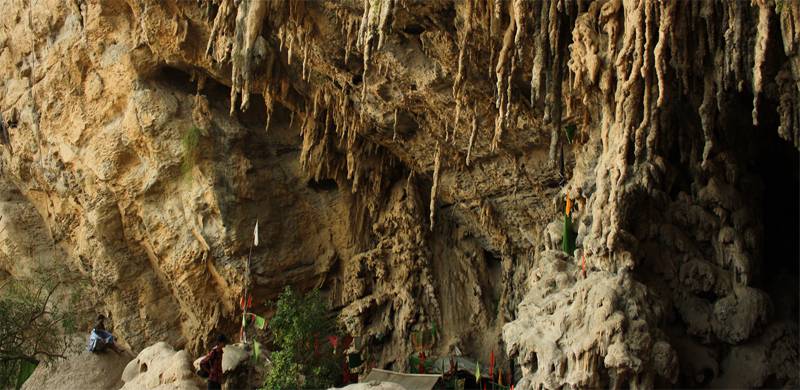

Lahut Lamakan cave in Balochistan (Source: Wikipedia/Umasha79)

Soon were we flying to Karachi airport, where dear Abdul Chang from Jamshoro University, a disciple of Adam´s, was waiting for us with a small van and a warm Sindhi smile, and off we went for hours and hours of frighteningly dusty roads and trails.

Late at night we arrived to our village; there we were told that the shrine we were looking for was “not very far away” further in the hills. Finally we reached a diminutive and pitch dark hamlet, pervaded by the sound of a quiet, yes quiet, drum, whose dim beat was sustaining the dance of the last believer in trance of the day.

In Pakistan, everybody seems to be aware – at least in the musical circuit – that a dancer who is undergoing a trance and “has lost control” has to be left alone and allowed to come back to his senses smoothly with the help of the diminishing rhythm of a respectful drum, lest he dies or gets in deep health trouble.

Actually, everybody would accuse a drummer of murder if he stopped beating his tabla or his dhol, before the person in trance “comes back”. Other adepts will take over, when the drummer has almost reached silence, to help with the “landing operation”, stroking the dancer and holding his hands, talking to him softly until he becomes himself again, safely grounded.

We shared the shrine´s flagging lamp and its cuisine with the drummer and we spent the night in an ample open shed for pilgrims, too tired to worry about the mosquitoes which managed to infect some of us with malaria. The next morning we enjoyed memorably warm nan and tea, not far from a little cemetery decorated with waving colourful rags, Buddhist style, flags and banners of the many cultures that this land has known and made meet.

Lahutis are pilgrims who travel to the Noorani’s shrine in Dhureji, Balochistan (Source: Umair Ahmed Shaikh)

And then we set for yet another expedition towards “the cave”. We had been informed at the shrine that our trip would be pointless if we did not enter “the cave”. The van dropped us at the beginning of the “holy trail” which through boulders and ravines led up to the cavern. After some time of steep climbing, we saw that there were pieces of rope tied to rocks and hanging trees, to help and guide the climbers but Mr and Mrs Sakata soon had to acknowledge that their health was not up to the mark and that they could not go on. Nevertheless they encouraged us to pursue, and said they would wait there, as long as necessary for our return and for our report.

On our way up we found a few other pilgrims, and several women with babies in their arms. Some of them were quite aged; grandmothers, worried for the health of their grandsons and granddaughters, who, unlike the old ladies I see around me, in the “literate” world, had iron legs, the elasticity of teenagers and showed a flabbergasting intrepidity with their tender load. Obviously, the healthy diet and the lack of cars and elevators in their lives had something to do with their endurance, but more than anything I think, it was the hope of seeing their little ones blessed or cured which gave them that extraordinary stamina, although there is an important factor to reckon with: the approach, the attitude of their society towards them: they are not pitied for being old, but respected and listened to; never stopped from action “due to their age”, free from “anti-aging “ concerns and quackeries, growing in power and responsibility as long and as much as nature admits.

Finally we attained the magic spot. There was a rope ladder to climb in order to get to the entrance of the dark grotto. A kind pilgrim, sticking to the touching solidarity we had noticed throughout our climb, held the foot of the ladder for us, and after some trembling and fearsome steps, there we were!

After a few initial minutes of blindness, I could only discern a small candle wavering on top of a kind of rocky altar in the background ,with a woman kneeling in front of it with her small child. Suddenly, a gentleman pulled my sleeve and with a smile I will never forget, he pointed to a corner to the right and murmured with bright eyes as of a child, “Here you have Noah´s Ark” floating on a small pond of water which dropped from the ceiling, was travelling some kind of stone shape which vaguely resembled a boat ,with a candle where the would-be mast would have been.

The grotto had many “apartments” and recesses, each with a name I began to realise, and with a small candle in front of which each pilgrim could choose to pray and/or pay his respects. With time my eyesight had become used to the twilight – and conditioned by the “spirit of the place” – and everything seemed more and more suggestive and wondrous.

It made me think of my childhood, when with my brothers, sisters and friends we would play and “explore” caves in the depths of the Old Castilian province of Avila, finding names to baptise each nook and corner of the caverns with the titles that our short repertoire of readings and our limited memory for awesome words could allow for, creating a real wonderland, such as this one in Lahut Lamakan.

Only the dwellers and baptizers here, in twenty first century Pakistan, were not children but adults, with the eyes, the strength ,and the Vis Poetica of children. I could have stayed there for ever.

But we had to go. Adam was adamant. I do not remember the way back, so engrossed was I with my stay in this fairy tale place where we were all full-fledged human beings, enjoying the power of both maturity and youth until we reached, on our way downwards, a gap that had to be jumped down and across by way of negotiation. Thank God Mr Sakata was there to counter the ten feet free fall with a smile and his strong arms. I wonder how did the pilgrim ladies manage on this stretch, with their babies and all.

Back in the village Mr and Mrs Sakata and Adam are interviewing and recording musicians, dancers and malangs around the fire, while I curl close to its heat, trying to recall what I felt this morning at the cave. A father makes his little son in his lap watch, with a majestic arm gesture out of his shawl, the beautiful dance of sparks and ashes flying like butterflies frightened by the crackling of the wood logs. The boy enraptured points at some fluttering entities.

It makes me sad to think that most probably, I will never be able to come back to the cave of Lahut Lamakan. And I am taken aback by the fear that the resurrection of my child´s eyes, and their devoted, and courageous gaze which I was able to share with other adults, just as deprived of shame and free from commonsensical logic as I was, remains there, in the cavern.

Never again the needful conjunction of persons and factors required to return will take place. Even though it is the most necessary shrine I have seen in Pakistan, the one I miss the most and the one that floods with melancholy my western life, missing “no end” as Adam would say, Pakistan, and its openings to the unknown and nevertheless felt, with its constant breakthroughs in the yet so wise realm of the “not scientifically proven” .

Lahut Lamakan is not only about trance and folklore, it happens to be “in charge” of quite a few sidelined truths of which it bears, generously, the full burden of proof. A true philosophical truce, for sooth!

May it live long and may it enlighten many an inner path for pilgrims to come.