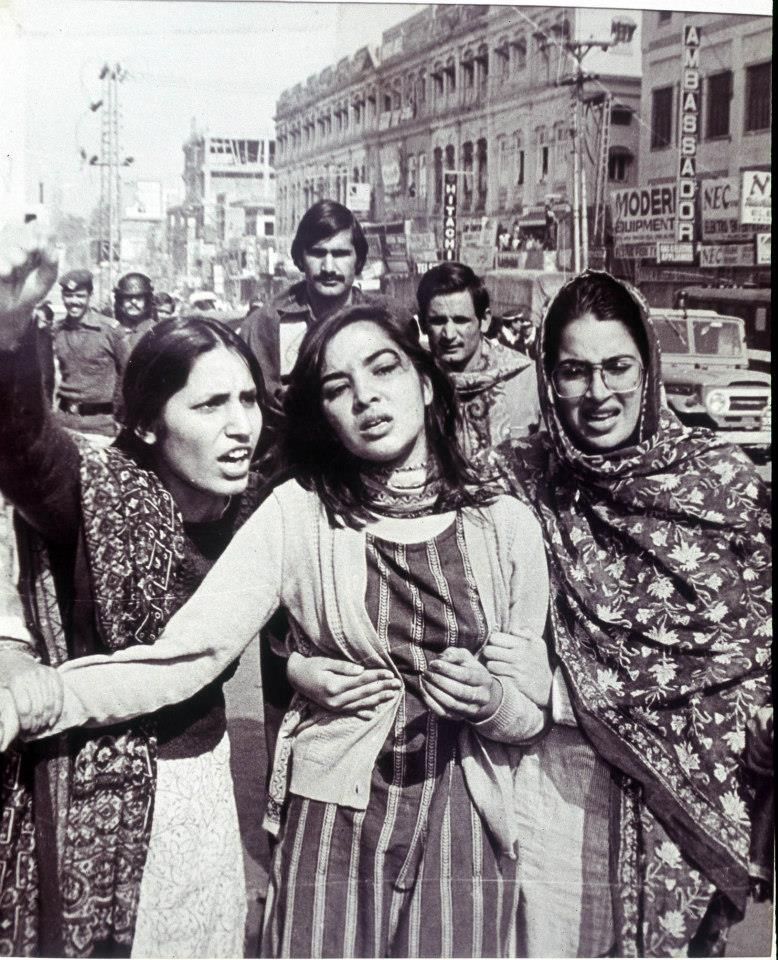

Is abridgment of certain historical events in historiography a legitimate practice? A scientific and carefully selective approach is the answer which modern historiography puts forward in response to the question. The history books—specifically text books of Pakistan study—written from a personality perspective sans a scientific and careful-selective approach are fraught with unilateral historical events. With a unilateral approach to historiography, contribution and advocacy of women for a united cause (in struggle for separate homeland) is abridged.

Take for example the historical account of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. Sir Syed and his Aligarh moment are perceived to be a watershed which turned the course of history (for Indian Muslims) towards modern education in subcontinent. Subsequently, to accentuate it further, eminent leaders such as Liaquat Ali Khan are said to be outcome of Aligarh moment. With an objective retrospection of historical events, social scientists such as Humza Alvi portray Sir Syed as a defender, who stood to safeguard the interests of a ‘salaried class’ which lost its reputation after British replaced Persian language with English.

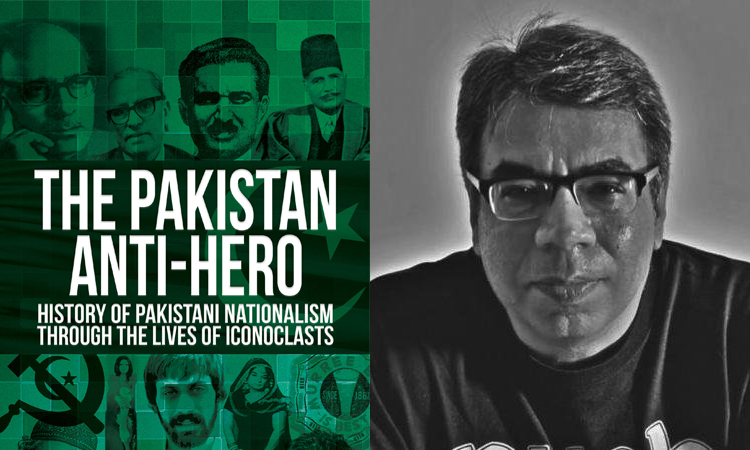

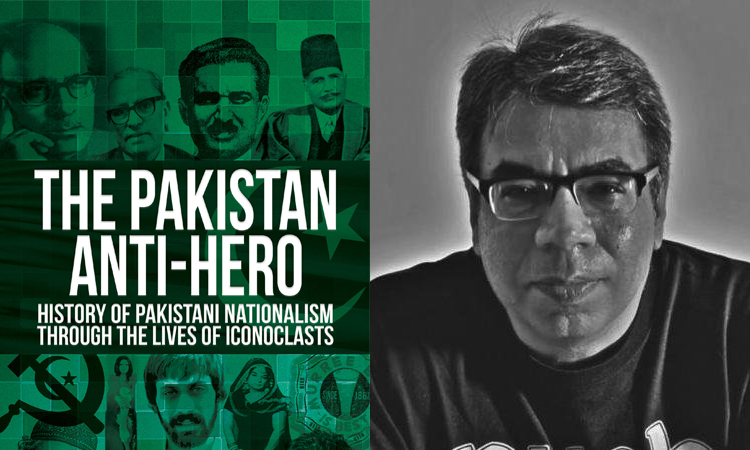

Surprisingly, the well-known critic of history text books in Pakistan, KK Aziz, during his expedition on correcting the historical course through his book ‘Murder of History’, glosses over the ‘unseen’—women as a part of history. In a similar way, prominent columnist and author Nadeem Farooq Paracha, in his book ‘The Pakistan Anti Hero’, accounts for the heroic history through the life of iconoclasts. The book tells an untold history linked with personalities who have never been mentioned in history text books. However, the historical account where women outnumbered or worked shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts falls out of the historical sheds.

For historical exclusion of women, the fault lines lie within a male dominated history. The Aligarh movement’s educational dispensation was structured over modern education but how far did the moment extend to women in terms of educating an as important segment of the Muslim community as male counterparts were?

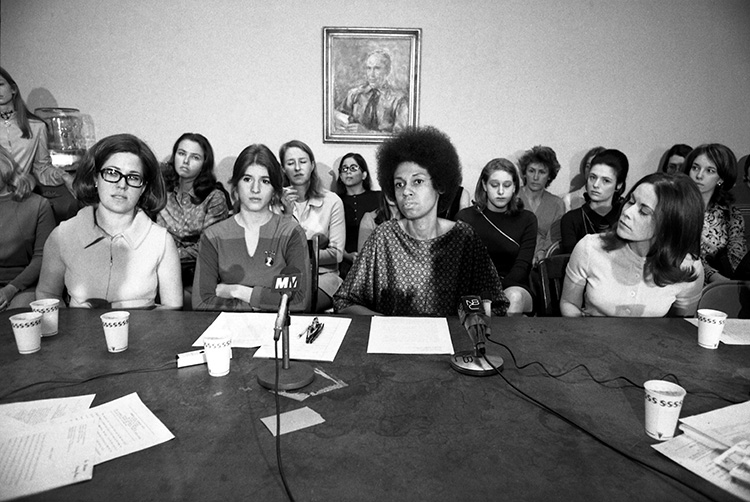

Viewing the history through a gender lens makes pathways to historical events epithetical to women and their socio-political struggle. For instance, along with the prominent names such as Sir Syed, who is considered to be the pioneer of modern education among Indian Muslims, names of many women went missing in history. Similarly, with respect to the missing historical accounts, Dr Rubina Saigol’s country study, Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Actors, Debates and Strategies, is an illuminating account of historical documentation of the women struggle.

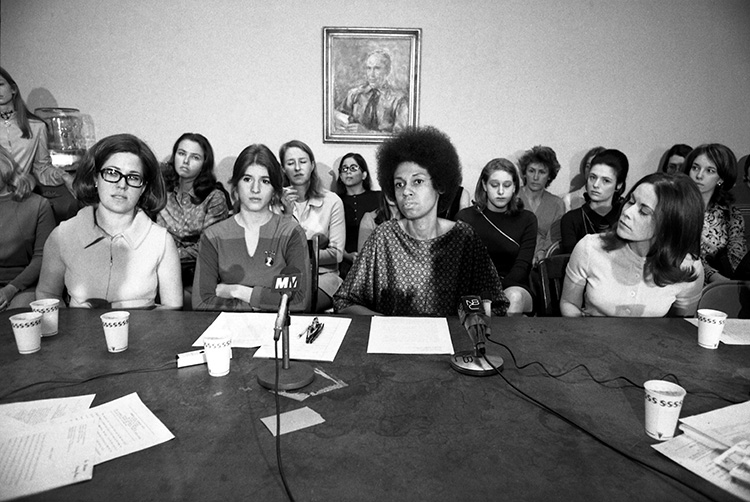

Historically, there is a good number of instances brought to light through study where women remained vocal during political, social and educational endeavour which led to the creation of Pakistan. Shaikh Abdullah’s name vanishes when Sir Syed receives accolades for reforming education. Shaikh Abdullah was among the first supporters of girls’ education. Despite facing opposition, he established a girls’ school which drew the attention of Begum of Bhopal. The latter supported the school and donated to develop a curriculum for school. In fact, the idea of a girls’ school culminated after the question of girls’ education was raised first time during annual meeting of Muhammadan Educational Conference (MEC) in 1899.

Subsequently, following the years when women educational movement grew popular, it was time women raised their voice through press and publication. By 1914, Shaikh Abdullah had brought out first Urdu journal for women, Khatoon, which, in the next few years, proved to be a stepping stone for numerous publications including Huquq-e-Niswan started by Syed Mumtaz and his wife Muhammadi Begum. The interwoven impact of educational struggle and press widened the educational awareness among women. The internecine struggle caused establishment of many girls’ schools. From 1904 to 1911 many girls’ schools, as Dr Rubina notes, were opened in Bombay, Calcutta, Aligarh, Lahore, Karachi and Patna.

Likewise, not only does flawed historiography abridge historical events which are essential to be part of history, it excludes social, educational and political contribution of women and press. Despite the fact that Jinnah was a staunch advocate of freedom of speech, which he went to a great length to defend, historiography remains more personality oriented.

As an important aspect of the freedom movement, vernacular press (English and Urdu) has never seen light of the day in historical accounts. With exclusion of press, history told through text books avoids the mention of publications which were brought out to vanguard educational and political rights of the women. Akhbar-e-Khawateen was one such weekly Urdu magazine which was founded in 1966. The magazine aimed at promoting women education and published inspiring stories of women involved in arduous works as strongly as male were involved in. in 1960s, the magazine introduced its readers to Mrs Nargis Hussain who was the first woman to join Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR).

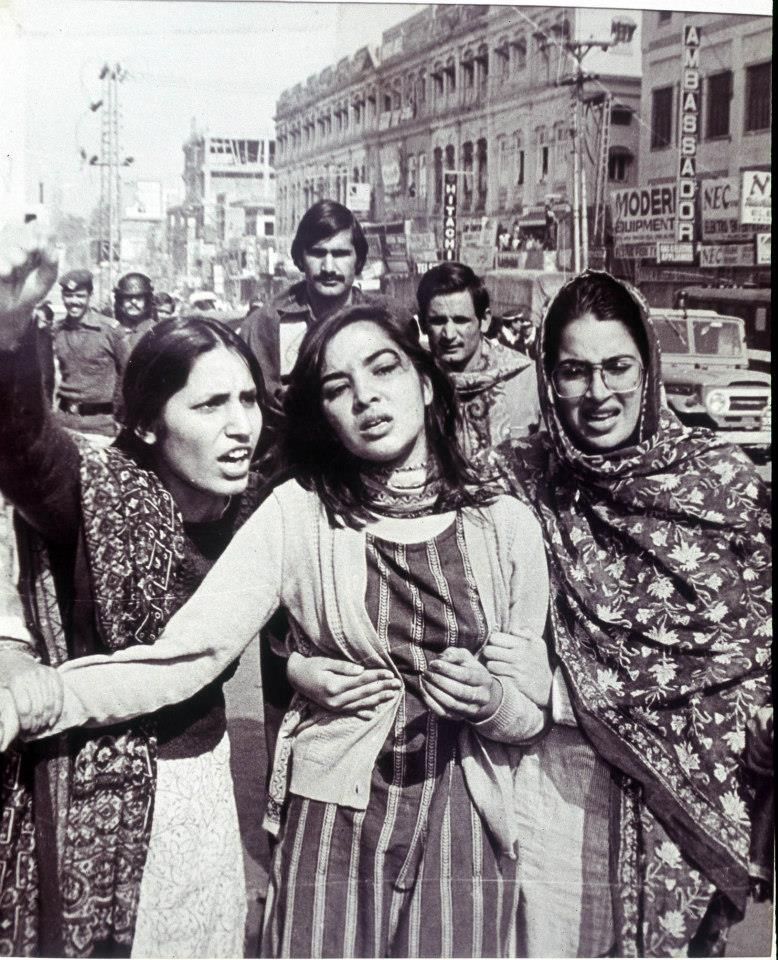

Ironically, the historiography sans a gender lens has drawn a stereotypical world through historical conduits. The stereotyped history, in turn, reflects the collective attitude of the society which confines women into a stereotypical frame.

Take for example the historical account of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. Sir Syed and his Aligarh moment are perceived to be a watershed which turned the course of history (for Indian Muslims) towards modern education in subcontinent. Subsequently, to accentuate it further, eminent leaders such as Liaquat Ali Khan are said to be outcome of Aligarh moment. With an objective retrospection of historical events, social scientists such as Humza Alvi portray Sir Syed as a defender, who stood to safeguard the interests of a ‘salaried class’ which lost its reputation after British replaced Persian language with English.

Surprisingly, the well-known critic of history text books in Pakistan, KK Aziz, during his expedition on correcting the historical course through his book ‘Murder of History’, glosses over the ‘unseen’—women as a part of history. In a similar way, prominent columnist and author Nadeem Farooq Paracha, in his book ‘The Pakistan Anti Hero’, accounts for the heroic history through the life of iconoclasts. The book tells an untold history linked with personalities who have never been mentioned in history text books. However, the historical account where women outnumbered or worked shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts falls out of the historical sheds.

For historical exclusion of women, the fault lines lie within a male dominated history. The Aligarh movement’s educational dispensation was structured over modern education but how far did the moment extend to women in terms of educating an as important segment of the Muslim community as male counterparts were?

Viewing the history through a gender lens makes pathways to historical events epithetical to women and their socio-political struggle. For instance, along with the prominent names such as Sir Syed, who is considered to be the pioneer of modern education among Indian Muslims, names of many women went missing in history. Similarly, with respect to the missing historical accounts, Dr Rubina Saigol’s country study, Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Actors, Debates and Strategies, is an illuminating account of historical documentation of the women struggle.

Historically, there is a good number of instances brought to light through study where women remained vocal during political, social and educational endeavour which led to the creation of Pakistan. Shaikh Abdullah’s name vanishes when Sir Syed receives accolades for reforming education. Shaikh Abdullah was among the first supporters of girls’ education. Despite facing opposition, he established a girls’ school which drew the attention of Begum of Bhopal. The latter supported the school and donated to develop a curriculum for school. In fact, the idea of a girls’ school culminated after the question of girls’ education was raised first time during annual meeting of Muhammadan Educational Conference (MEC) in 1899.

Subsequently, following the years when women educational movement grew popular, it was time women raised their voice through press and publication. By 1914, Shaikh Abdullah had brought out first Urdu journal for women, Khatoon, which, in the next few years, proved to be a stepping stone for numerous publications including Huquq-e-Niswan started by Syed Mumtaz and his wife Muhammadi Begum. The interwoven impact of educational struggle and press widened the educational awareness among women. The internecine struggle caused establishment of many girls’ schools. From 1904 to 1911 many girls’ schools, as Dr Rubina notes, were opened in Bombay, Calcutta, Aligarh, Lahore, Karachi and Patna.

Likewise, not only does flawed historiography abridge historical events which are essential to be part of history, it excludes social, educational and political contribution of women and press. Despite the fact that Jinnah was a staunch advocate of freedom of speech, which he went to a great length to defend, historiography remains more personality oriented.

As an important aspect of the freedom movement, vernacular press (English and Urdu) has never seen light of the day in historical accounts. With exclusion of press, history told through text books avoids the mention of publications which were brought out to vanguard educational and political rights of the women. Akhbar-e-Khawateen was one such weekly Urdu magazine which was founded in 1966. The magazine aimed at promoting women education and published inspiring stories of women involved in arduous works as strongly as male were involved in. in 1960s, the magazine introduced its readers to Mrs Nargis Hussain who was the first woman to join Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR).

Ironically, the historiography sans a gender lens has drawn a stereotypical world through historical conduits. The stereotyped history, in turn, reflects the collective attitude of the society which confines women into a stereotypical frame.