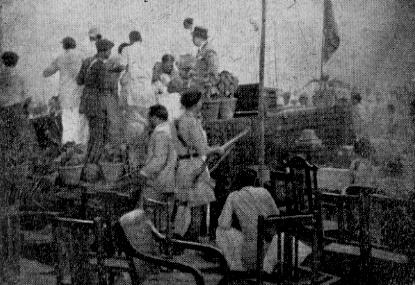

The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, arrives with his sister, Fatima Jinnah, to raise the flag of Pakistan in Karachi. In his first address, he was hopeful that Pakistan would become a modern and pluralistic Muslim-majority country.

However, by 1948, the country was embroiled in its first war with India and a schism of sorts had developed between Jinnah and his erstwhile comrade, Liaquat Ali Khan – the first PM of Pakistan. Suffering from tuberculosis, Jinnah passed away in September 1948, leaving behind a huge leadership vacuum. One which many believe is yet to be filled.

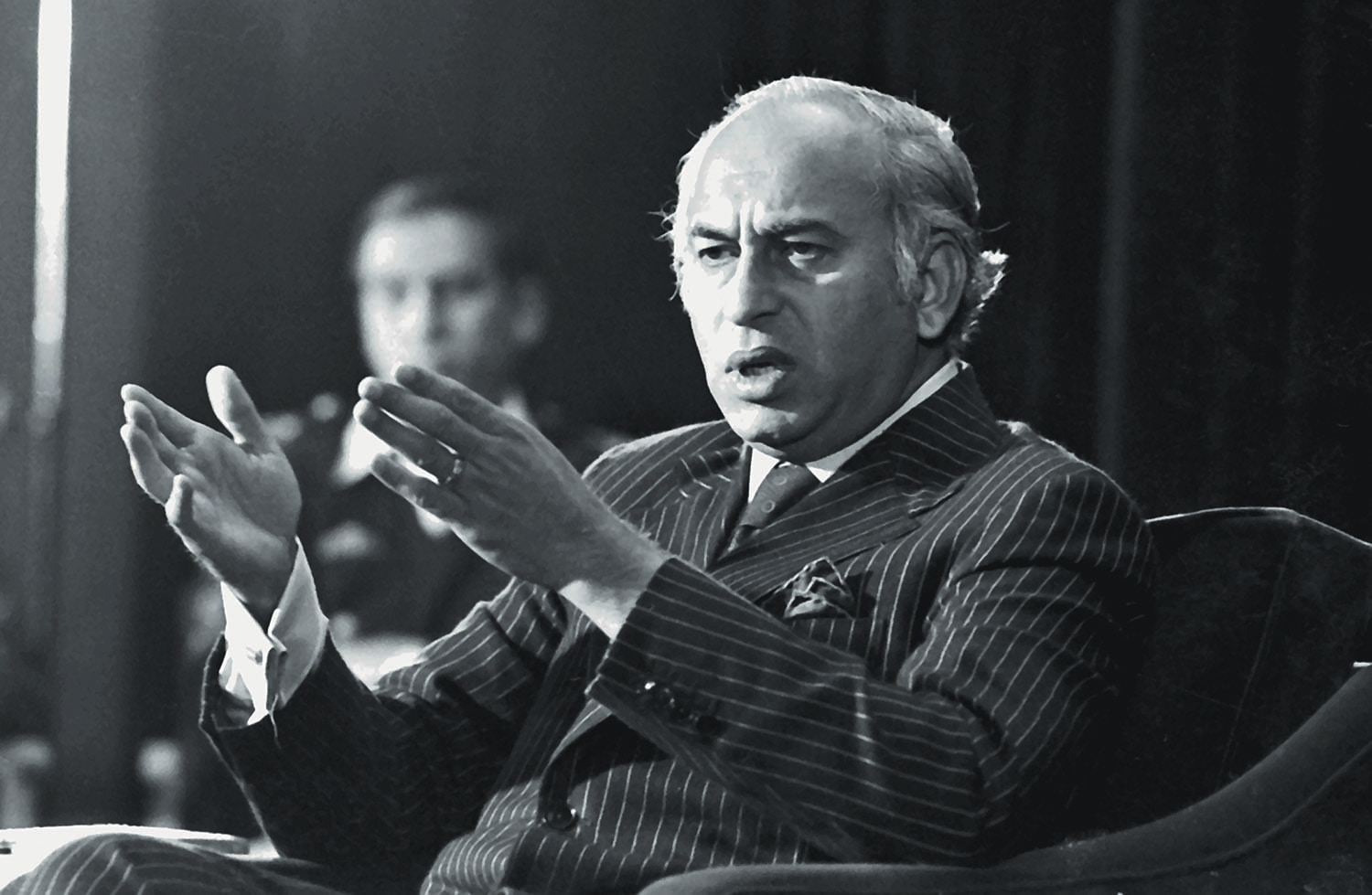

May 1950: Pakistan’s first PM, Liaquat Ali Khan, speaks at a banquet during his visit to the United States – first by a Pakistani head of government. Historians inform that after Pakistan’s creation in August 1947, leaders of the new country were invited for a visit by the time’s two competing superpowers, the US and the communist USSR.

Two years later, PM Liaquat decided to by-pass the Soviet invitation and instead visit the US. Thus began Pakistan’s long and sometimes torrid relationship with the US. Instead of remaining neutral in the Cold War between the two superpowers, Pakistan categorically sided with the US.

This eventually led to Pakistan receiving financial and military aid by the US in return for total support, an anti-communist stance, and military bases in Pakistan.

His decision to visit US was largely influenced by the fact that the US had become the country’s first major buyer of its agricultural products; and also because there was a heavy anti-communist bias within Pakistan’s powerful bureaucracy and military.

Police and fellow politicians surround the dying body of PM Liaquat in Rawalpindi. Liaquat was assassinated at a rally in 1951. Even though an Afghan/Pashtun nationalist, Saeed Akber, was caught red-handed on the spot, he was shot dead by the police.

There are now only theories about why he shot Liaquat, and, more so, why he was killed on the spot by the police instead of being arrested and interrogated.

Soon, the officer who was investigating the murder died in a ‘mysterious’ plane crash. Investigation into the murder was reopened in 1958 and it transpired that Saeed Akbar was an Afghan who had been expelled by his country before Pakistan’s creation. He was living in Peshawar (which was under British rule then).

He continued receiving money from the government of Pakistan after the country’s creation. He was sitting in the ‘security enclosure’ at the rally. How he managed to do that?

Nevertheless, the reinvestigation in 1958 could not proceed because an important file that an investigation police officer was carrying had been destroyed when the plane he was in, crashed.

Till this day no convincing explanation has emerged – even though Ayub Khan (president of Pakistan between 1958 and 1969) did inform that the careers of many politicians and bureaucrats blossomed after Liaquat’s murder, hinting that they might have been involved.

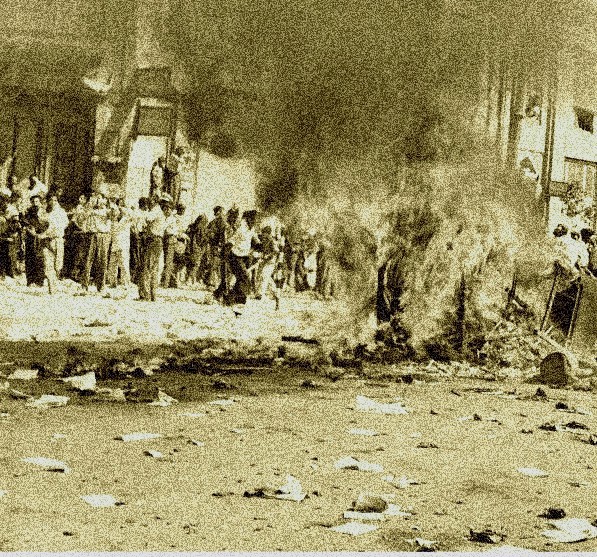

Anti-Ahmadi activists go on a rampage in Lahore in 1953. Spurred by religious parties, their activists killed numerous members of the Ahmadi community and destroyed their property.

The government of Khawaja Nazimuddin send in the army which crushed the commotion and arrested the main leaders of the agitating groups.

Military courts handed down death sentences to some major leaders of the protesting outfits. These sentences were later reversed on an appeal.

The agitating parties were demanding the ouster of the Ahmadi community from the fold of Islam and the dismissal of Ahmadi personnel from government and state institutions.

The state and government of Pakistan rejected these demands and instead crushed the agitators, accusing them of being anti-Pakistan and ‘miscreants opposed to the ideas of Jinnah and Iqbal.’

During a 1954 inquiry held by two senior judges, it was established that the riots had been ‘tacitly’ instigated by the Chief Minister of Punjab, Mumtaz Daultana, for two reasons: (1) To divert the attention from an economic crisis his provincial government was facing; and (2) He wanted to embarrass and oust the PM because he (Daultana) believed he was more suited for the PM’s position.

The inquiry also warned that religious parties wanted to create a totalitarian theocracy (‘a religious Leviathan’).

Both Daultana and Nazimuddin were dismissed by the governor-general and the religious parties retreated.

1958: President Iskandar Mirza, PM Feroz K. Noon and Military Chief Ayub Khan at the Karachi Airport.

Shortly after this photo was taken, Mirza and Khan dismissed Noon’s indirectly elected coalition government and declared the country’s first Martial Law.

Causes given for the coup were ‘rising corruption’, ‘political instability,’ and ‘peddling of Islam for political gains.’

Only a few weeks after the coup, Ayub ousted Mirza as well, accusing him of trying to divide the army. Ayub became Field Marshal and in 1959 got himself ‘elected’ as president. He banned all political parties.

He lambasted the parties on the left for being reckless adventurers and Soviet stooges; and parties on the right ‘for trying to present Islam as an anti-progress faith.’

He promised to construct a Pakistani nationalism which would entirely be based on ‘Jinnah’s vision’ which, to Ayub, meant: A modern country driven by a progressive and dynamic Islam; a robust market economy; and defended by a strong, powerful military.

He also changed the country’s name. The 1956 Constitution had declared Pakistan an ‘Islamic Republic.’ Ayub abrogated the constitution and renamed the country, ‘Republic of Pakistan.’

An early press ad of the Pakistani national airline, PIA. PIA came into being in 1955 when the government nationalized the privately-owned Orient Airways. In the 1960s, PIA began its accent as one of the top airlines in the world.

It was also the first airline to introduce the concept of onboard entertainment. Jaqueline Kennedy, wife of US President JF Kennedy, is said to have commented that PIA was her favorite airline.

As the airline’s popularity grew, in 1967 it commissioned the famous French fashion designer, Pierre Cardin, to design the uniforms of PIA pilots and stewardesses, which he did.

In the 1970s the airline expanded its fleet and routes.

In 1975 the airline commissioned Hardy Amies, the designer of clothes worn by England’s Queen Elizabeth, to design new uniforms for PIA stewardesses.

In 1979 the airline acquired the ownership of America’s famous and historic Roosevelt Hotel in New York.

In the early 1980s, PIA engineers and pilots helped the UAE launch Emirates Airlines.

Unfortunately, from the late 1980s onwards, PIA’s fortunes began to slowly decline. By the early 2000s the airline was in a state of disarray and bankruptcy. It’s still hovering there.

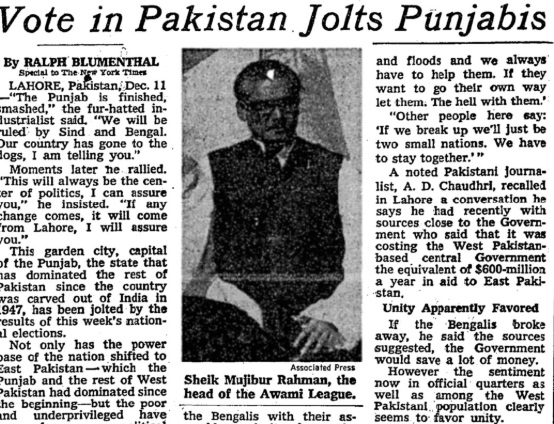

A provocative headline in a British newspaper on the result of the 1970 election in Pakistan.

Ayub Khan had resigned in March 1969 at the height of a protest movement against his regime.

He handed over power to Gen Yahya Khan who agreed to hold the country’s first direct elections for national and provincial assemblies.

The Bengali nationalist party, the Awami League (AL) swept the election in East Pakistan. In West Pakistan, ZA Bhutto’s PPP won the largest number of seats. According to this report, the industrial and business classes of West Pakistan’s largest province, Punjab, were perturbed to see parties led by a Bengali, Sheikh Mujeeb (AL), and a Sindhi, ZA Bhutto (PPP), outgun all the other parties in the election.

The report highlights the fear among West Pakistan’s economic elite that (under an AL-led government) the balance of power would shift to East Pakistan.

On the other hand, the same elites were also concerned about a PPP-led set-up because the party’s manifesto had promised to implement certain radical socialist policies.

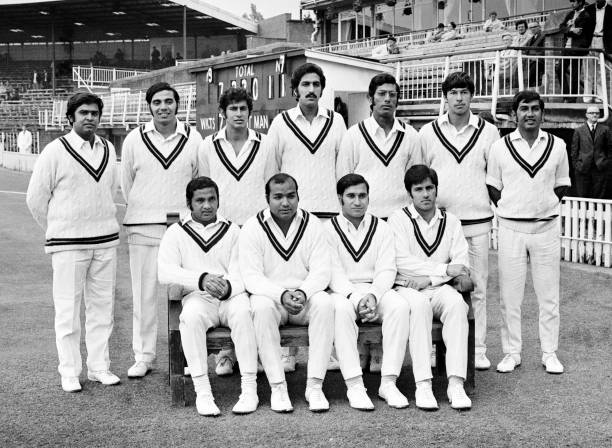

The Pakistan IX for the first Test during the team’s June/July 1971 tour of England.

The tour was marred by controversy when one of the team’s opening batsmen, Aftab Gul (standing first from left) refused to sign a bat that was to be auctioned to raise money for cyclone victims of East Pakistan.

Gul had been a fiery leftist student leader at the Punjab University in 1968-69. A talented batsman, he was inducted into the side during a Test match against England in Lahore in 1969 at the height of the anti-Ayub movement. This was done to appease the students who were planning to disrupt the game.

The 1971 tour was held when a civil war had erupted in East Pakistan. The PPP had refused to attend the first session of the assembly. Bhutto said his party would not attend unless AL withdrew ‘it’s (Bengali) separatist stance.’

Yahya Khan eventually came around to the same view and decided to launch an all-out military action against militant Bengali nationalists in East Pakistan.

The Pakistani left was divided on the East Pakistan issue. The pro-Soviet factions were against military action in East Pakistan; the pro-China faction was for it. It was also anti-India. The socialists and communists in the PPP were pro-China. Gul too belonged to the pro-China faction of the left.

In England he claimed that the money from the auctioned bat will land in the hands of militant Bengali nationalists. So he along with a few other players refused to sign the bat. Yahya Khan intervened through the Pakistan Embassy in London and ordered the players to sign the bat.

They eventually did. Gul was the last one to do so. Nevertheless, in December 1971, Bengali nationalists (with help from India) managed to break East Pakistan away. It became Bangladesh. Yahya was ousted and replaced by ZA Bhutto and his PPP.

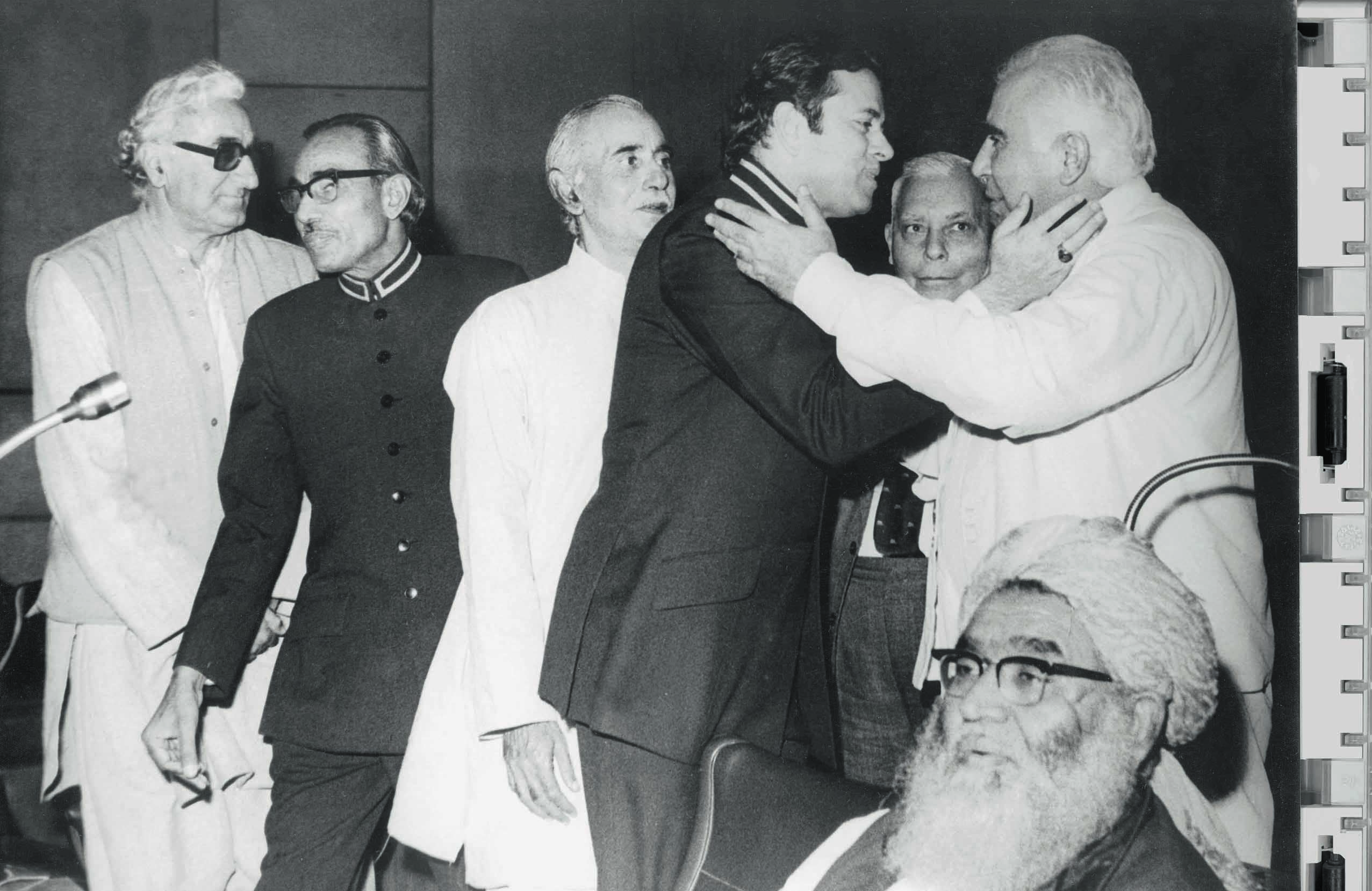

August, 1973: Some members of the PPP embrace opposition party leaders in the National Assembly after both agreed to pass a new constitution in 1973.

The constitution rechristened Pakistan an ‘Islamic Republic,’ but there was much debate and differences on the meaning of the term between the ruling PPP and parliamentarians belonging to the religious parties.

Both, however, agreed that Pakistan was to become a parliamentary democracy. The PPP rejected the proposal of injecting certain ‘Sharia laws’ in the constitution, but agreed to make the learning of Arabic, Islamiat and ‘Pakistan Studies’ compulsory in schools.

The constitution was activated on Pakistan’s 26th Independence Day (14 August, 1973).

Leading members of the Ahamadi community gather outside the National Assembly in 1974 to explain their point of view to a committee. The comittee was investigating a parliament bill introduced by religious and opposition parties to constitutionally oust the Ahmadi from the fold of Islam.

In 1974, religious outfits had initiated a fresh movement for this purpose. The movement turned violent. The Bhutto regime refused to discuss the issue in the parliament and threatened to crush it like it was done in 1953.

However, increasing violence (in Punjab) and reports that some PPP members in the Punjab Assembly were planning to side with the opposition, forced Bhutto to allow the religious parties to introduce the bill.

A committee was formed to hear the views of religious scholars from all Muslim sects and sub-sects in Pakistan. A delegation from the Ahmadi community too was invited.

But it seems it failed to deter the members of the parliament from introducing an amendment in the constitution (the 2nd Amendment) which turned the community into a non-Muslim minority in Pakistan.

The irony is, the community had largely voted for the PPP in the Punjab during the 1970 election.

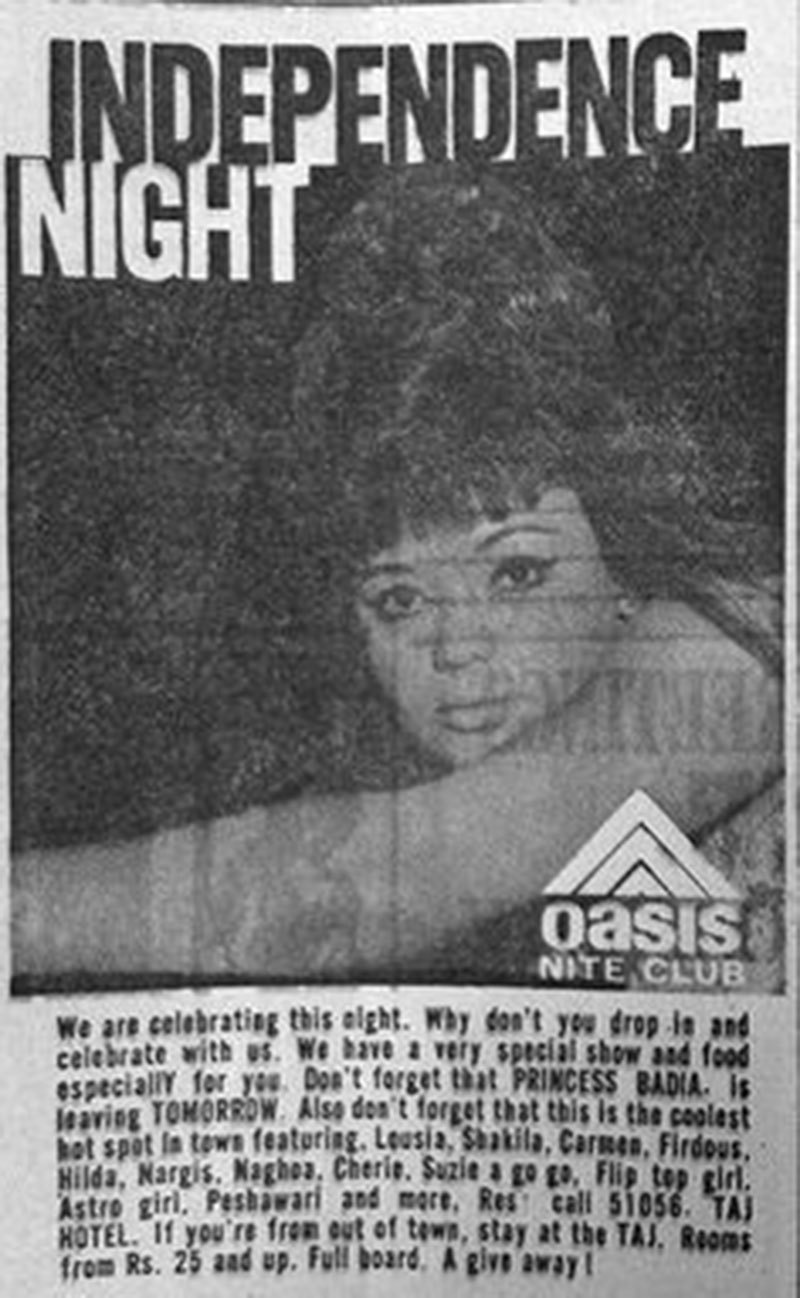

A 1975 press ad of a nightclub in Karachi. According to the 1977 booklet, Tourism in Pakistan, published by the Ministry of Tourism, Karachi had 6 nightclubs between 1959 and 1970. Their number increased to 14 between 1970 and 1976.

It was in 1963 that Karachi was given the title, ‘City of Lights’ by the Ayub regime. Whereas Lahore was seen as the country’s ‘cultural capital,’ Karachi was explained as ‘Pakistan’s economic hub and entertainment capital.’ It also had the largest number of hotels and cinemas.

The upscale nightclubs in the 1970s included, Playboy and Oasis;the Metropole Gardens (which was in Hotel Metropole); and the club in Hotel Intercontinental. ‘Medium range’ clubs were the Penthouse and Star-Lite at Saddar’s Hotel Excelsior; 007 at Hotel Beach Luxury; La Gourmat at Palace Hotel; Lado; and the clubs at Hotel Midway; Lado; and Imperial Hotel.

Apart from the bars at the clubs and the hotels, the booklet also informs that there were about two dozen bars (‘pubs’) which were mostly located in the Saddar area and on Tariq Road.

According to the booklet, the overall tourism industry of Pakistan saw an increase in the mid and late 1960s and then again in the mid-1970s. ‘Tourist hotspots’ at the time were Swat, Khyber Pass, Lahore, Mohenjo-Daro and Karachi.

Sale of liquor (to Muslims) was banned in April 1977 when the Bhutto regime was pushed into a corner by a protest movement led by an alliance of religious parties and anti-Bhutto outfits. The nightclubs were also closed down, including a massive casino which was to open (in March 1977) on the shores of the Clifton Beach. Serving of alcoholic drinks on PIA flights too was stopped.

Bhutto had explained the ban as a temporary measure. But the ban was strengthened by a 1979 Ordinance issued by the Zia-ul-Haq regime which replaced the Bhutto government through a military coup (July 1977).

Only ‘licensed’ liquor stores were allowed to sell their products to non-Muslim Pakistanis and non-Muslim visitors. Almost all such shops are located in Karachi and other areas of the Sindh province and in Quetta and few other towns of Balochistan.

Besieged by a violent protest movement against his regime in March 1977, ZA Bhutto holds a press conference at his residence in Karachi. In it he accused the United States and Pakistan’s business community and industrialists of ‘bankrolling’ the opposition parties. The opposition parties had accused his government of rigging the 1977 election.

His regime was toppled by Gen Zia in a reactionary military coup in July 1977. He was arrested and charged for getting a political opponent murdered in 1974. Through a controversial trial, he was sentenced to death. He was hanged in April 1979.

1982: Surrounded by celebrities, Pakistan hockey captain, Akhtar Rasool, lifts the 1982 Hockey World Cup trophy for the fans to see after landing with his team in Lahore. The cup was won in India.

This was Pakistan’s third Hockey World Cup title, and second consecutive World Cup victory. Pakistan was the world’s No: 1 ranked hockey side at the time. Pakistan will win just one more Hockey World Cup title (in 1994) before it began its long downward slide.

Today it is struggling to even hold its No: 13 position. It failed to qualify for the 2014 World Cup event.

Gen Zia with US President Ronald Regan during Zia’s 1984 visit to the US.

Reagan was one of Zia’s biggest supporters and benefactors. Both worked closely to fund and arm Afghan insurgent groups against the Soviet-backed regime in Kabul and the Soviet army stationed there.

Reagan as president dished out billions of dollars’ worth of aid to the Zia regime and equated the Afghan insurgent groups to America’s founding fathers. Consequently, the US turned a blind eye to blatant human rights violations of the Zia dictatorship against political opponents, women and minorities.

The Reagan-Zia partnership radicalized thousands of Muslims, many of who later mutated into becoming vicious militant and terrorist outfits. Years later, most terror organizations that haunted Muslim countries (especially Pakistan) and then Europe and US as well, had/have their roots in the Afghan Civil War of the 1980s that the US (and Saudi Arabia) bankrolled and the Zia regime facilitated.

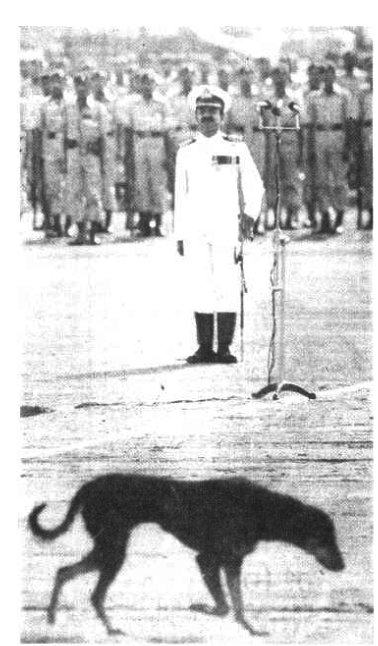

A stray dog manages to enter the area where Zia was witnessing a march-past of troops. Zia’s Information Ministry was not very happy when this photo was carried by some newspapers.

Some believed that the dog was released in the area by anti-Zia students, but this was never confirmed.

The Zia regime ended after 11 years when he died in a plane crash in August 1988. Sabotage was hinted, but never convincingly proven.

Just days after Zia’s demise on August 18, 1988, spontaneous political rallies emerged – especially on the roads of Karachi and Lahore. They weren’t organized by party activists, as such, but by supporters.

Most of these were ‘car rallies’ taken out by PPP and MQM supporters in Karachi and by the PPP and PML in Lahore. They mostly included urban middle-class men and women. Even policemen who were sent to keep a check on them joined the festivities.

The rallies led to the 1988 elections which were won by Benazir Bhutto’s PPP.

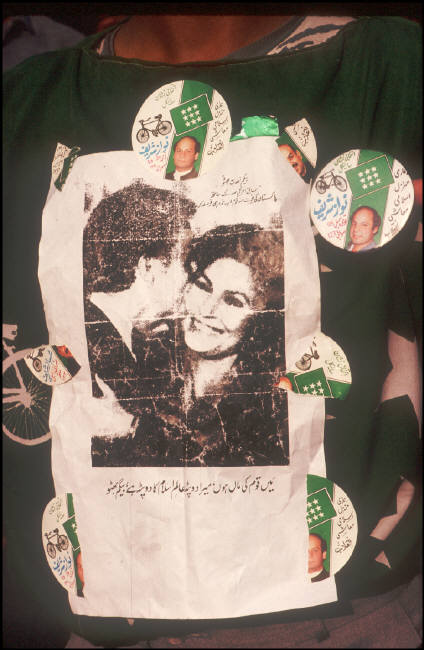

A PML supporter wearing a T-Shirt showing ZA Bhutto’s widow, Nusrat, being embraced by an America man. The rivalry between Benazir’s PPP and Nawaz Sharif’s PML-N was vicious across the 1990s.

During 1988 and 1990 elections, PML activists often created such posters and T-Shirts to rouse the sentiments of PML’s ‘conservative constituencies.’

PML and PPP won two elections each in the 1990s. Their governments were all cut-short by pro-establishment and trigger-happy presidents (armed with a constitutional amendment introduced by late Zia which gave the president the power to dismiss elected regimes).

Nawaz’s second government (1996-99) was, however, toppled in a military coup.

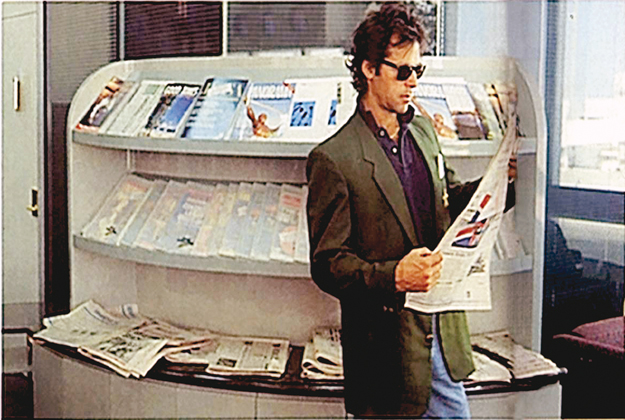

A somber Pakistan cricket captain, Imran Khan, reads a newspaper at the Sydney Airport during the 1992 Cricket World Cup in Australia.

According to famous photographer, Iqbal Munir, who took this photo, Khan at the time was ‘detached and aloof from the rest of the team,’ and Pakistan had lost most of its opening matches.

Munir (in his book Eye on Imran) then added that Khan’s demeanor suddenly changed just before the team’s ‘do-or-die match’ against hosts, Australia. Munir said that Vice-Captain Javed Minadad played a major role in bringing about this change.

With a mixture of fighting spirit, good cricket and luck, Khan eventually managed to lead Pakistan into the final and defeat England to lift the World Cup trophy.

This win would go a long way in also helping Khan build his leadership credentials as a politician. 26 years later, his party the PTI (formed by him after his retirement from the game) managed to win a slim majority in the 2018 election, making Khan Pakistan’s 22nd prime minister.

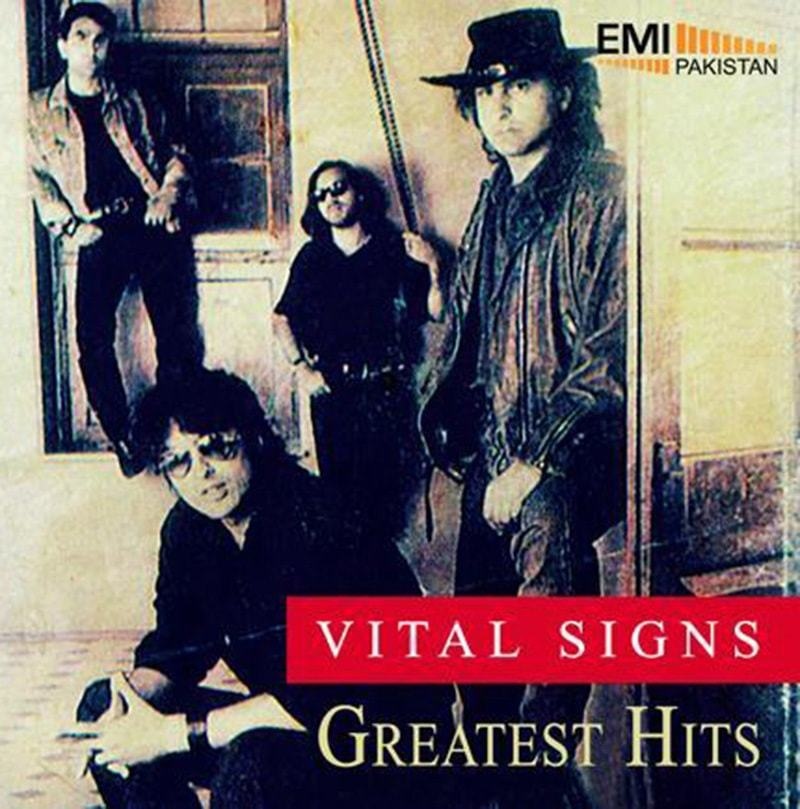

A 1994 ‘Greatest Hits’ album cover of Pakistani pop band, Vital Signs. The Signs led a wave of local pop and rock acts which suddenly rose in the late 1980s after the end of the Zia dictatorship.

Though dozens of modern pop and rock acts continued to emerge till the wave began to recede in the late 1990s, the Signs remained to be the country top pop draw.

However, relations between the band members were always fragile. The band hired and fired at least four guitarists (all the firings were contentious). The core members often squabbled among themselves as they held differing musical and political views.

The band finally folded in 1998. Its lead singer, Junaid Jamshed, who quit music all together and became a member of an apolitical Islamic evangelical outfit, tragically died in a plane crash in 2016.

General Parvez Musharraf emerges from a PTV station in Rawalpindi after delivering his first ‘address to the nation’ in 1999. He had toppled the second Nawaz Sharif regime in a dramatic military coup. This was Pakistan’s fourth such coup.

Musharraf immediately outlined his plans to undo ‘the chaos of the 1990s’ and build a ‘new Pakistan’ based on an idea he called ‘enlightened moderation.’

Under the Musharraf regime (1999-2008), Pakistan enjoyed some impressive economic growth and the opening up of various modern cultural vistas. He also ordered a clamp down on extremist groups.

However, by 2006, the impressive economic bubble that his regime had inflated, began to burst and his policies against extremist groups began to implode. He was forced to resign after a popular movement against him erupted in 2007.

Later Musharraf maintained that the movement was ‘bankrolled by the Sharifs of PML-N.’ He also bemoaned that his own institution, the military, did not support him when he was being cornered by the movement. He was asked to resign by the PPP regime which came to power after the 2008 election.

Now living in exile in Dubai, he still believes many Pakistanis want him back.

Former Pakistan cricket captain Misbah-ul-Haq during Pakistan’s 2016 tour of England. From a discarded batsman, Misbah rose to become the country’s most successful Test captain.

After losing his place thrice in the team between 2002 and 2010, Misbah made a fourth comeback in late 2010 at age 36. But this time he returned as a make-shift captain.

This was a period when Pakistan cricket was facing serious match-fixing charges and severe in-fighting. On the other hand, extremist violence and bomb attacks had paralyzed life in Pakistan and no team was willing to visit the country.

Slowly but surely, Misbah picked up the pieces. He first reestablished his place in the side as a reliable batsman, and then as a firm but empathetic captain, managing to gradually pull back Pakistan cricket from the brink.

The Pakistan Test side was hovering at the bottom end of world rankings when he took over. Six years later in 2016, he had led it to become the No: 1 ranked Test side in the world.

Misbah’s style of leading not only brought back respectably to Pakistan cricket, but he also became a friendly and wise face of a country ravaged by extremism.

Misbah was given a rousing farewell when he retired in 2017.

Former Pakistan army chief, General Raheel Sharif doesn’t look amused. Made the new army chief in 2013 by the third Nawaz Sharif regime, Gen Raheel had pushed hard his narrative which proclaimed that Pakistan faced a greater internal threat (from extremist groups) than an external one.

His urge to kick-start a widespread military operation against extremist outfits whose violent acts had paralyzed the country. This urge was often frustrated by a reluctant government and by some other parties inside and outside the parliament.

In December 2014 when extremists slaughtered over 140 students at a school in Peshawar, Gen Raheel aggressively pushed the government to hold an all parties’ conference and produce a consensus on green-lighting a military operation.

After getting the go-ahead from the parliament, the military launched an unprecedented operation against varied militant groups.

By 2017 when he retired, the country saw a 70 percent drop in suicide bombings.

However, he remained unsatisfied at the regime’s reluctance to implement the National Action Plan (NAP) that was to tackle the non-militant aspects of extremism in society.

A tourist takes a walk in Gilgit-Baltistan. In 2018, the US TV news network, the CNN, listed Pakistan (especially its scenic northern areas) as one of 2018’s most beautiful and tourist-friendly destinations.

Imran Khan, elected PM in 2018, meets military chief Gen Bajwa at the military headquarters in Rawalpindi.

Khan’s party won a slim majority in the 2018 election. His opponents claim the elections were ‘rigged’ and that the rigging was ‘facilitated by the military.’ The military has had a rocky relationship with the country’s two oldest mainstream parties, the PPP and the PMLN.

However, on the other hand, some observers have suggested that Khan’s ‘better relations with the military’ will make it easy for it to conduct its on-going operations against the militants, even though Khan was originally opposed to such an operation.

The military also expects Khan’s government to fully implement NAP which the Nawaz regime was somewhat reluctant to do for various political reasons.

Interestingly, Khan’s centre-right party, the PTI, made the implementation of NAP as one of the central planks of its 2018 manifesto.