If looked at the brighter side, even something as outrightly barbaric as colonialism stands a chance of being justified. Apologists for colonialism often use this trademark approach to sweep the British colonial atrocities under the carpet – upon which, then, they construct their sandcastle of ‘advantages of colonialism’.

Ascribing advantages to a policy that was premised on oppression not only downplays the endless sufferings that were endured by the millions but also undermines rational thinking. If we start measuring even the most heinous of the acts in terms of the accidental benefits that they might have delivered, as in the case of colonial rule of India, we lose the yardstick to differentiate between the good and bad. But since possessing any such yardstick was least of their concerns, the colonists, and later their apologists, mustered the gall to claim benefits out of the Britain’s sordid rule of the subcontinent.

Democracy, Bureaucracy, and the vast Railway network

Apologists often cite democracy, bureaucracy, and the vast railway network inherited by the succeeding nations – Pakistan and India – as some of the ways in which the British rule benefited the natives. A casual analysis of the historical facts, however, reveals that British introduced the above-mentioned means in order to protect and promote their own vested interests, aimed at the ruthless exploitation of the subcontinent.

Far from delivering them, British systematically trampled the ideals of justice, equality and representation

Democracy, to begin with, is the amalgamation of the ideals of justice, equality, freedom of expression, and representation – conversely, far from delivering these values, the British systematically trampled them. The colonial legal system was inherently corrupt and biased against the Indians, allowing the British to commit crimes with impunity and get away with them. European masters were exonerated from the charges of torturing their Indian servants to death on the basis of medical reports that would reveal the Indians to have ‘weak insides’. Similarly, while the Britons were trailed exclusively by the European judges, Indians faced warrantless arrests. The Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, in a mockery of fundamental human rights, notified several ethnic and social communities of India for possessing ‘criminal tendencies’, thereby sanctioning the social persecution of over thirteen million people. Members of these tribes were routinely subjected to arbitrary searches, thrashings and arrests – all of which was done under a law that negated the universal axiom of justice: The right of every individual to be deemed innocent until proven otherwise.

When the Raj hit its all-time low

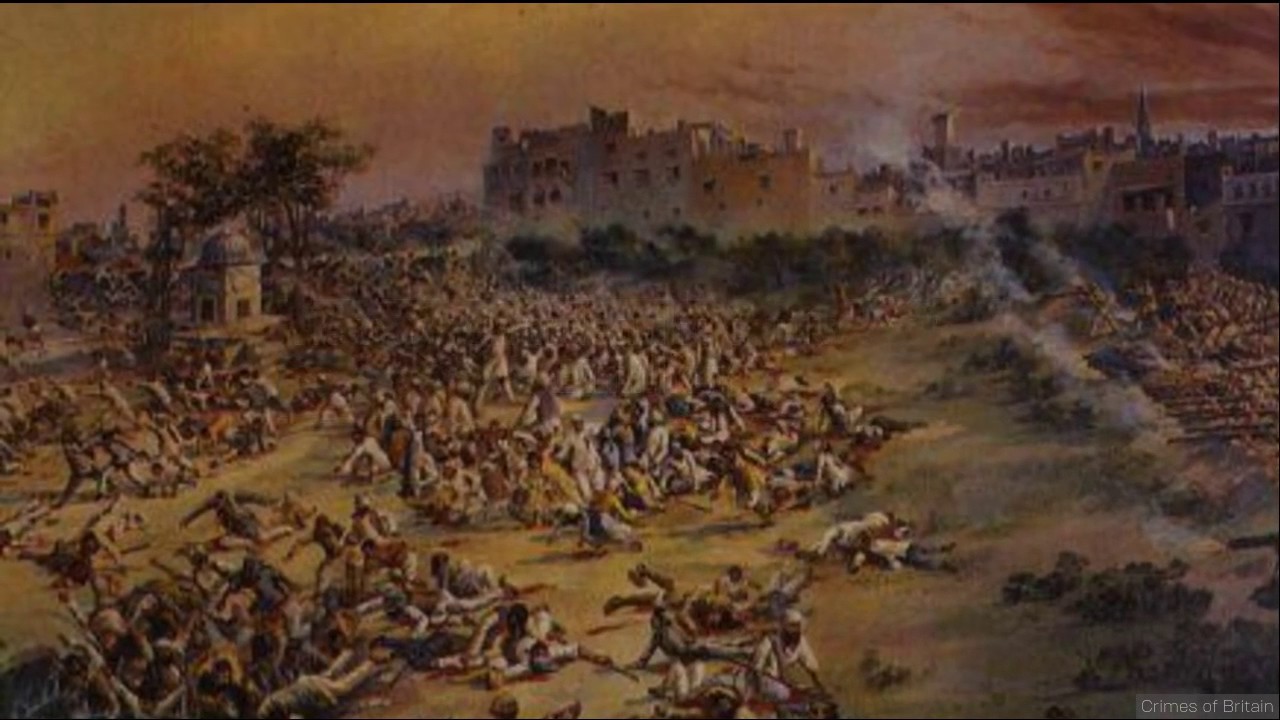

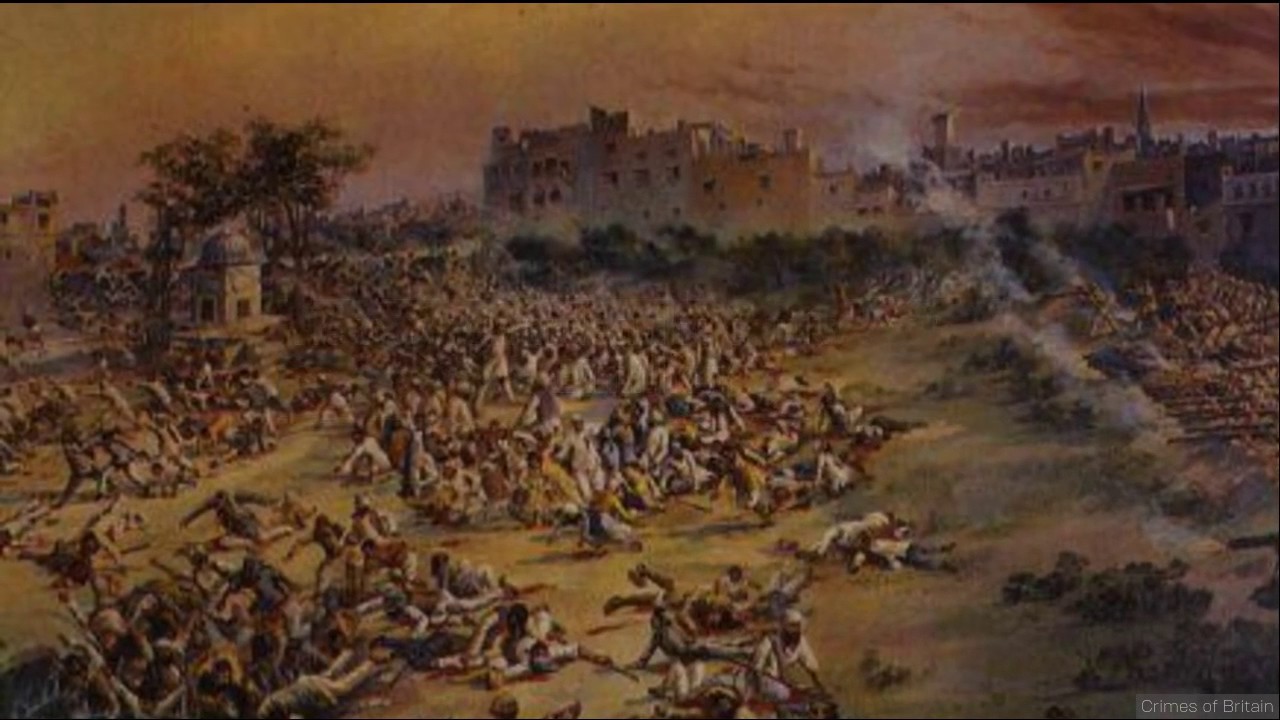

Critical voices challenging the legitimacy of the Raj and its repressive policies were suppressed by the authorities using draconian sedition regulations. Two of such notorious laws, the Vernacular Act and Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, were employed by the British to control the press and prohibit demonstrations, which deprived Indians of the opportunity to convey their legitimate grievances. Every form of dissent, whether verbal or print, was taken as an attempt to ‘excite dissatisfaction towards the government’ and therefore punishable with hefty fines and sentences amounting to life imprisonment. The Raj hit the all-time low when its troops, under the command of General Dyer, massacred the peaceful protestors at Jallianwala Bagh in a despicable episode of state-sponsored terrorism – the aching memory of which persists to this day.

Only 3% of Indian population was allowed to vote for the Central Assembly

Being the ruling party of the subcontinent, British resolved not to allow the Indians to enter the governing sphere and challenge their hegemony. Therefore, the role of Indians in mainstream politics always remained restricted with only 3% of the Indian population being allowed to vote for the Central Assembly; an adjustment was made no sooner than 1935. The kind of ‘democracy’ introduced by the British was a diametric opposite of what a true democracy is supposed to be. Neither was it meant to transmit democratic traditions to the Indians, nor to improve the political landscape of the subcontinent, as claimed by the apologists. Plagued by gross injustice and bigotry, this so-called democracy was nurtured by the British with the sole aim of maintaining their unyielding dominance over the Indians.

Deputy Commissioner to date instills fear in the hearts of Pakistanis

The Raj, in order to further its imperial pursuits, rendered yet another gift to the subcontinent – the all-powerful, barely-accountable bureaucracy. Bureaucrats, recruited in the Indian Civil Service, were vested with enormous magisterial, revenue-collection, and administrative powers without being subjected to any elected body. This lack of check over the bureaucrats concentrated the power in the executive branch of the government – a bitter legacy which fostered the post-independence civil services along the colonial lines: to rule, not serve the people. Thus, it is not entirely surprising to find that even today the slightest mention of the word “DC” (Deputy Commissioner) – the bureaucratic head of a district in Pakistan – instills more in people’s minds the fear of authority than the contentment of being looked after; a legacy highly reminiscent of the colonial times when the natives were treated as subjects rather than citizens.

Subcontinent’s world GDP share dropped from a towering 23% in 1600 to a record low of 3% in 1940

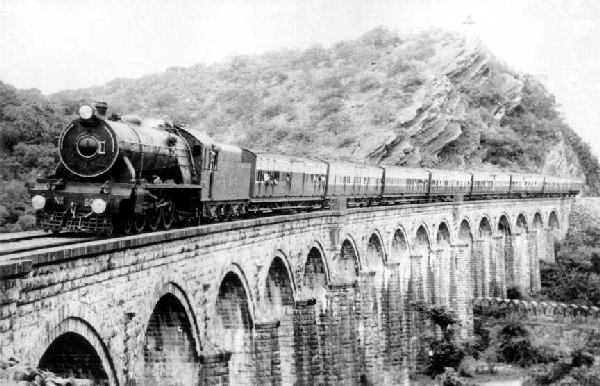

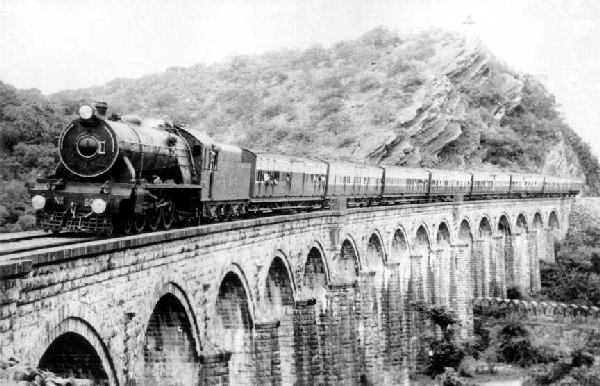

Subcontinent’s vast railway network is also frequently cited by the apologists as the major contribution of the British to the region; this claim, however, glosses over several inconvenient truths. The railways were primarily constructed by the British to transport the extracted resources to the ports, from where they were shipped off to England. All the major harvests of India – cotton, indigo, jute etc. – were used as raw materials to feed the Britain’s industrial boom while deadly famines would rage in Bengal, devouring millions, including the cultivators of these very crops. Therefore, the claim that British built railways for the economic prosperity of the subcontinent is not only deplorable but also contrary to the established facts; subcontinent’s world GDP share dropped from a towering 23% in 1600 to a record low of 3% in 1940 – the credit of which solely rests with the British and their blatant exploitation of the Indian resources.

Once the context is established, this sandcastle of ‘advantages’ crumbles

Certainly, it does not take much of a rigorous inquiry to conclude that under the garb of democracy, bureaucracy and railways were instruments with which the contours of a totalitarian regime were traced; while some mechanisms were meant to perpetuate the British in power, others were intended to satiate their imperial ambitions. No wonder why the apologists are fond of quoting these ‘advantages’ in isolation from their context. For, once the context is established, this sandcastle of ‘advantages’ crumbles, unveiling an era riddled with murder, plunder and occupation.

Ascribing advantages to a policy that was premised on oppression not only downplays the endless sufferings that were endured by the millions but also undermines rational thinking. If we start measuring even the most heinous of the acts in terms of the accidental benefits that they might have delivered, as in the case of colonial rule of India, we lose the yardstick to differentiate between the good and bad. But since possessing any such yardstick was least of their concerns, the colonists, and later their apologists, mustered the gall to claim benefits out of the Britain’s sordid rule of the subcontinent.

Democracy, Bureaucracy, and the vast Railway network

Apologists often cite democracy, bureaucracy, and the vast railway network inherited by the succeeding nations – Pakistan and India – as some of the ways in which the British rule benefited the natives. A casual analysis of the historical facts, however, reveals that British introduced the above-mentioned means in order to protect and promote their own vested interests, aimed at the ruthless exploitation of the subcontinent.

Far from delivering them, British systematically trampled the ideals of justice, equality and representation

Democracy, to begin with, is the amalgamation of the ideals of justice, equality, freedom of expression, and representation – conversely, far from delivering these values, the British systematically trampled them. The colonial legal system was inherently corrupt and biased against the Indians, allowing the British to commit crimes with impunity and get away with them. European masters were exonerated from the charges of torturing their Indian servants to death on the basis of medical reports that would reveal the Indians to have ‘weak insides’. Similarly, while the Britons were trailed exclusively by the European judges, Indians faced warrantless arrests. The Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, in a mockery of fundamental human rights, notified several ethnic and social communities of India for possessing ‘criminal tendencies’, thereby sanctioning the social persecution of over thirteen million people. Members of these tribes were routinely subjected to arbitrary searches, thrashings and arrests – all of which was done under a law that negated the universal axiom of justice: The right of every individual to be deemed innocent until proven otherwise.

This lack of check over the bureaucrats concentrated the power in the executive branch of the government – a bitter legacy which fostered the post-independence civil services along the colonial lines: to rule, not serve the people. Thus, it is not entirely surprising to find that even today the slightest mention of the word “DC” (Deputy Commissioner) – the bureaucratic head of a district in Pakistan – instills more in people’s minds the fear of authority than the contentment of being looked after

When the Raj hit its all-time low

Critical voices challenging the legitimacy of the Raj and its repressive policies were suppressed by the authorities using draconian sedition regulations. Two of such notorious laws, the Vernacular Act and Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, were employed by the British to control the press and prohibit demonstrations, which deprived Indians of the opportunity to convey their legitimate grievances. Every form of dissent, whether verbal or print, was taken as an attempt to ‘excite dissatisfaction towards the government’ and therefore punishable with hefty fines and sentences amounting to life imprisonment. The Raj hit the all-time low when its troops, under the command of General Dyer, massacred the peaceful protestors at Jallianwala Bagh in a despicable episode of state-sponsored terrorism – the aching memory of which persists to this day.

Only 3% of Indian population was allowed to vote for the Central Assembly

Being the ruling party of the subcontinent, British resolved not to allow the Indians to enter the governing sphere and challenge their hegemony. Therefore, the role of Indians in mainstream politics always remained restricted with only 3% of the Indian population being allowed to vote for the Central Assembly; an adjustment was made no sooner than 1935. The kind of ‘democracy’ introduced by the British was a diametric opposite of what a true democracy is supposed to be. Neither was it meant to transmit democratic traditions to the Indians, nor to improve the political landscape of the subcontinent, as claimed by the apologists. Plagued by gross injustice and bigotry, this so-called democracy was nurtured by the British with the sole aim of maintaining their unyielding dominance over the Indians.

Deputy Commissioner to date instills fear in the hearts of Pakistanis

The Raj, in order to further its imperial pursuits, rendered yet another gift to the subcontinent – the all-powerful, barely-accountable bureaucracy. Bureaucrats, recruited in the Indian Civil Service, were vested with enormous magisterial, revenue-collection, and administrative powers without being subjected to any elected body. This lack of check over the bureaucrats concentrated the power in the executive branch of the government – a bitter legacy which fostered the post-independence civil services along the colonial lines: to rule, not serve the people. Thus, it is not entirely surprising to find that even today the slightest mention of the word “DC” (Deputy Commissioner) – the bureaucratic head of a district in Pakistan – instills more in people’s minds the fear of authority than the contentment of being looked after; a legacy highly reminiscent of the colonial times when the natives were treated as subjects rather than citizens.

Subcontinent’s world GDP share dropped from a towering 23% in 1600 to a record low of 3% in 1940

Subcontinent’s vast railway network is also frequently cited by the apologists as the major contribution of the British to the region; this claim, however, glosses over several inconvenient truths. The railways were primarily constructed by the British to transport the extracted resources to the ports, from where they were shipped off to England. All the major harvests of India – cotton, indigo, jute etc. – were used as raw materials to feed the Britain’s industrial boom while deadly famines would rage in Bengal, devouring millions, including the cultivators of these very crops. Therefore, the claim that British built railways for the economic prosperity of the subcontinent is not only deplorable but also contrary to the established facts; subcontinent’s world GDP share dropped from a towering 23% in 1600 to a record low of 3% in 1940 – the credit of which solely rests with the British and their blatant exploitation of the Indian resources.

Once the context is established, this sandcastle of ‘advantages’ crumbles

Certainly, it does not take much of a rigorous inquiry to conclude that under the garb of democracy, bureaucracy and railways were instruments with which the contours of a totalitarian regime were traced; while some mechanisms were meant to perpetuate the British in power, others were intended to satiate their imperial ambitions. No wonder why the apologists are fond of quoting these ‘advantages’ in isolation from their context. For, once the context is established, this sandcastle of ‘advantages’ crumbles, unveiling an era riddled with murder, plunder and occupation.