Evidence detailed in Pakistan's nuclear bomb: A story of defiance, deterrence and deviance indicated that it is very hard to make sweeping generalizations about the nuclear proliferation episode involving Pakistan because different sets of motivations, players and circumstances influenced the transfer of sensitive technology from Islamabad to Tehran, Pyongyang and Tripoli.

The study authored by Pakistani-American academic Hassan Abbas claimed that in the absence of a clear chain of command, as well as loose monitoring mechanisms surrounding the nuclear program of Pakistan, the clandestine Abdul Qadeer Khan network successfully manipulated and hoodwinked the government in Islamabad for several years before it was caught.

Abbas, who teaches at National Defense University in Washington, also argued that the political worldview of high-ranking officials in Pakistan during the proliferation period, some examples of which are cited in a research paper, particularly Abdul Qadeer Khan, was a critical factor which exacerbated the proliferation risk and played a huge role in the decision to put the nuclear expertise of the country on sale. Khan was the manager-in-chief of the nuclear assets of Pakistan, and other officials usually stopped short of questioning or challenging him, according to interviews the author conducted with concerned personnel and a study cited in the book.

As Pakistan depended heavily on this network of nuclear smugglers for the development of the nuclear program, these individuals continued, and even expanded, their criminal syndicate after Pakistan had developed the bomb, and Khan often helped them.

However, AQ Khan was assisted in the transfer of sensitive technology across international borders by greedy European engineers and businessmen, who wanted to get rich quickly, and he was able to operate without alerting the global non-proliferation regime of suspicious activities, the book underlined, citing testimony from a senior US official. As Pakistan depended heavily on this network of nuclear smugglers for the development of the nuclear program, these individuals continued, and even expanded, their criminal syndicate after Pakistan had developed the bomb, and Khan often helped them.

Why did Pakistan decide to develop nuclear weapons?

The author of the book provided an interesting backdrop to the nuclear story of Pakistan, and was of the view that in order to understand what drove rogue individuals within the nuclear program to market the technology, it was also important to comprehend why Pakistan developed an atomic bomb in the first place. According to the professor, the nuclear ambitions of Pakistan were primarily driven by a desire to counter India.

The dispute over the Kashmir valley heightened tensions between the neighbors, and two wars with New Delhi, one of which resulted in the break-up of Pakistan, removed any doubts as to Indian strategic designs on the subcontinent.

This animosity towards the Hindu-majority country was rooted in the bloody history of partition. Pakistan experienced financial and administrative troubles at inception which threatened the security of the infant state, and the generally callous attitude of the Indian National Congress to these insecurities formed the basis of rivalry with India. The dispute over the Kashmir valley heightened tensions between the neighbors, and two wars with New Delhi, one of which resulted in the break-up of Pakistan, removed any doubts as to Indian strategic designs on the subcontinent.

Another important consideration for Pakistan in the development of an offensive nuclear policy was that the conflict with India had made Islamabad realize that alliances with other nations, even powerful ones, were no guarantee of safety, and the author also cited research that corroborated this view. United States and China, despite being very close friends with Pakistan, had failed to safeguard the territorial integrity of the country in 1965 and 1971.

Therefore, according to the strategic calculus of Pakistani officials, the country needed a credible deterrent to counter Indian hegemony. Hence, the decision to build a nuclear bomb after India had developed it was only natural and realistic, noted Abbas.

Making the bomb

Pakistan signed a civilian nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States under Atoms for Peace deal in 1955 and set up the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission in 1956. This agreement allowed Pakistan to obtain funding for a small research reactor and other technical literature related to nuclear sciences.

However, progress afterwards was slow, until Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto took charge of the Ministry of Fuel and Power in 1958, the author noted, referencing complaints by senior officials and testimony of Bhutto. He set up a nuclear research institute and dispatched many dozens of young Pakistanis abroad for nuclear studies. The minister attracted many Pakistanis working in European nuclear programs to Pakistan, and obtained funding for them to pursue their activities in their home country, a study referenced in the book noted. During the 1960s, France and Canada also helped Pakistan with the setting up of nuclear facilities.

The reluctance of the administration of President Ayub to pursue a full-scale nuclear weapons program, however, was a hurdle which Bhutto could not surpass, claimed Abbas, citing the doctoral research of scholar Mansoor Ahmed. This changed after the break-up of Pakistan in 1971, which hurt Pakistani pride, and Bhutto knew the country had to look at something other than conventional weapons to counter blatant Indian aggression.

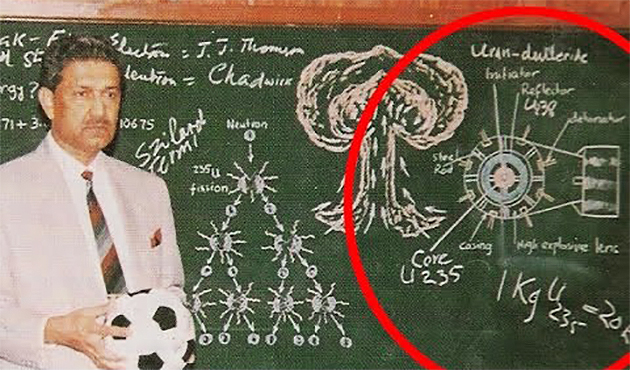

After meeting Bhutto, Khan convinced the former Pakistani premier that uranium enrichment offered an alternative, and a shorter route, to the nuclear bomb. Bhutto eventually established the Engineering Research Laboratories, later renamed Khan Research Laboratories, in 1976 for Khan to work independently within Pakistan.

After India conducted a nuclear test in 1974, the strategic balance in South Asia, which had been delicately maintained since partition, changed overnight. Within days, Pakistan also made a policy decision and secretly decided to pursue the development of a nuclear bomb, according to credible research. The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission was tasked to produce weapons-grade plutonium, which was the most efficient pathway to making a bomb.

It was also in 1974 that Bhutto received a letter from AQ Khan, who was working in the Netherlands, and wanted to help Pakistan move up the nuclear ladder. After meeting Bhutto, Khan convinced the former Pakistani premier that uranium enrichment offered an alternative, and a shorter route, to the nuclear bomb. Bhutto eventually established the Engineering Research Laboratories, later renamed Khan Research Laboratories, in 1976 for Khan to work independently within Pakistan.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tffdp2kSt-s

Bhutto was removed from office in 1977, but the nuclear program continued. As Pakistan helped the US fight Russian invasion of Afghanistan by using militant proxies, Washington turned a blind eye to the nuclear ambitions of Pakistan. According to Hassan Abbas, Pakistan conducted the first cold test of a nuclear bomb as early as 1983. Fifteen years later, when India formally conducted nuclear tests in 1998, Pakistan responded the same month and successfully tested atomic weapons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UnH3VT6muYQ

Throughout this whole process, according to Abbas, the individuals invoked in the development of the bomb faced stiff resistance from colleagues and competitors, as well as powerful states like the US. The progress of the Pakistani nuclear bomb was hampered by a lack of scientific expertise, domestic political opposition and the hawkish view of international players, according to Hassan Abbas. With India pursuing the development of nuclear weapons with relative freedom, Pakistanis felt a sense of betrayal by the West, and this sense of injustice galvanized the work of Pakistani scientists.

Nuclear proliferation

The book details the links between the Pakistani nuclear program and the Iranian, North Korean and Libyan nuclear weapons. According to the professor, the decision to transfer technology was made by certain influential individuals within the government who took advantage of administrative chaos to gain power and prestige.

Hassan Abbas maintained that during the three critical periods in which nuclear proliferation activity of AQ Khan and his associates was at its peak (1987-1989, 1993-1995 and 1997-1999), political instability and civil-military tensions in Pakistan created an enabling environment for the nuclear smugglers to take advantage of constant crisis to influence decisions in their favor.

For example, shortly before the government of Muhammad Khan Junejo was dismissed by President Zia in 1988, there were visible tensions between the executive authority and the office of the president. There were differences between the prime minster and the president with regards to important appointments and transfers to top civil and military posts, and the attempt by Junejo to slash the defense budget drew a swift categorical response from the military dictator.

According to former president Pervez Musharraf, no audits of the Khan Research Laboratories were carried out by the government and even the security of the institution was left to the scientist. Funds were given to KRL, but no mechanism was in place to monitor them.

After the assassination of General Zia-ul-Haq, democracy returned to Pakistan, but the withdrawal of the Soviets from Afghanistan meant the US lost interest in the region. Aid stopped, and Washington started asking tough questions about the nuclear program of Pakistan. Sanctions followed, and the security establishment started getting concerned about a possible attack on Pakistani nuclear facilities. Similar attacks had taken place in Syria, Iraq and Iran. The prime minsters of the time were generally kept out of the loop regarding these sensitive issues, according to Abbas.

Another issue which merits attention in this proliferation saga is that the command and control surrounding the nuclear facilities of Pakistan in earlier days was abysmal. According to former president Pervez Musharraf, no audits of the Khan Research Laboratories were carried out by the government and even the security of the institution was left to the scientist. Funds were given to KRL, but no mechanism was in place to monitor them.

According to Abbas, AQ Khan enjoyed 'complete freedom' in his management of the nuclear program during the Zia era, and reported directly and personally to the highest authorities, without any hurdles. After suspicions started being raised regarding the assets of Khan, which were deemed beyond his known sources of income, the security circles started getting uneasy. Musharraf even recommended the setting up of a National Command Authority to oversee security affairs, with a Strategic Plans Division within that body tasked with handling nuclear security. A National Accountability Bureau investigation into AQ Khan's finances in 2000 also found numerous discrepancies in his accounts, but NAB decided not to pursue them in the interest of national security.

Khan was a devout Muslim, and based his worldview around an anti-West agenda, which explains his dealings with states like Iran, North Korea and Libya, maintains Abbas. Personal ambitions, financial benefits, nationalism, anti-American feelings and a devout sense of Islamic identity all played a part in his decision to proliferate nuclear technology to other countries.

The personal ambition and worldview of AQ Khan played a critical role in the proliferation of nuclear weapons, stressed the author of the study. Khan invested a lot of time and effort into developing his image as the 'father of the Pakistani nuclear bomb', and derived his power from the support of the political and military elite, as well as nationalist and religiously conservative forces.

The front cover of Time Magazine's February 2005 edition

Apart from a greed for money, professional rivalry with the PAEC also fueled Khan’s ambitions. He was encouraged to engage in parallel business dealings to make KRL financially independent, and these dealings eventually provided the cover for him to make more clandestine deals with foreign governments. Abbas noted that the patriotism of Khan was also a factor in his proliferation activity, because Khan believed that he had saved Pakistan from Indian aggression, and giving nuclear weapons to other countries would ease international pressure on Pakistan.

Khan was a devout Muslim, and based his worldview around an anti-West agenda, which explains his dealings with states like Iran, North Korea and Libya, maintains Abbas. Personal ambitions, financial benefits, nationalism, anti-American feelings and a devout sense of Islamic identity all played a part in his decision to proliferate nuclear technology to other countries.

In conclusion, the Pakistani-American academic added that the AQ Khan network operated internationally through a multinational umbrella group which has bases in several regions, including Europe, Middle East, East Asia and North America. The study revealed that almost 30 companies sold nuclear-related goods using AQ Khan, and his European associates were instrumental in this regard, who were resourceful and networked enough to escape attention.