By Nadeem F. Paracha

Editor's note: Ever since the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement gained power, 'Pashteen Cap' has been in the limelight, with many of the Pashtuns endorsing it. Contrary to the love it gained, there have been a lot of suspicious and knee-jerk reactions given by the state and its security forces, assuming it as some kind of a threat to nation. Having mentioned that, Nadeem Farooq Paracha traces the history of such symbolically celebrated caps which actually gained state's attention overtime.

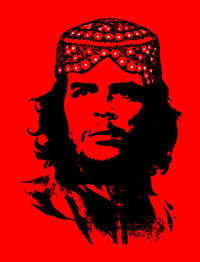

Recently, supporters of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movemnt (PTM) flooded the social media claiming that security forces in the tribal areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) were arresting anyone wearing the ‘Pashteen cap.’ The cap, also known as the Mazari topi or Mazari cap, is said to have originated hundreds of years ago in the Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif.

It was made famous among young Pashtuns of Pakistan not too long ago by PTM’s 24-year-old leader, Manzoor Pashteen, who can be seen always wearing it.

Pashteen is a fiery orator and activist who has been leading a movement against what he says is the Pakistani state’s neglect of the rights of the Pashtuns and the long-time disfigurement of the Pashtun identity. Pashteen believes that both the state as well as the extremists continue to explain the Pashtun community as being inherently and culturally aggressive.

Truth is, this image of the Pashtun community was originally concocted by the British in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was then willingly adopted by the community itself before the state of Pakistan reoriented it to mean a religiously charged people willing to ‘defend Islam’ through the barrel of the gun.

This image too was largely adopted by many members of the Pashtun community until the community was devastated by the consequent emergence of various reactionary militant groups from within.

Pashteen’s movement today is looking to dispel this identity that has become a cultural burden for the Pashtun. But it is doing this by putting the blame entirely on the state of Pakistan and ignoring the fact that this damaging identity was once willingly assumed by many sections from within his own community.

This is one reason why the state of Pakistan is reacting the way it is against the PTM. So whereas on the one hand the ‘Pashteen cap’ on a young Pashtun’s head symbolizes his or her desire to refigure the community’s identity, on the other hand, to the state of Pakistan, it has begun to symbolize a threat of sorts.

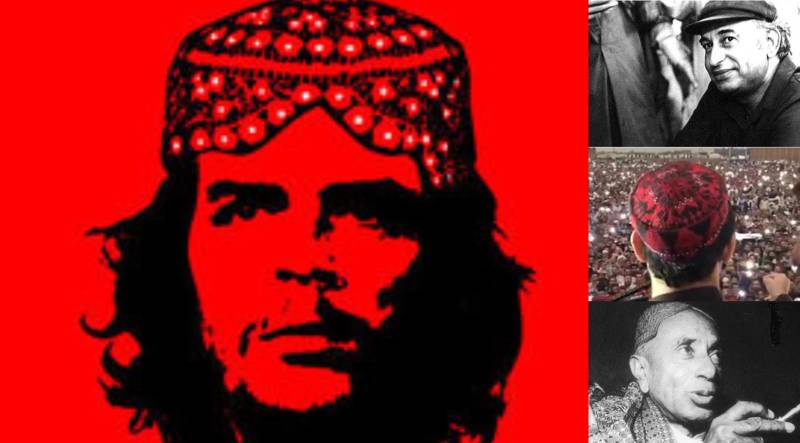

Interestingly, this is not the first time in Pakistan that a cap has been looked at with such suspicion. Once the red cap worn today by the mainstream Pashtun nationalist outfit, the Awami National Party (ANP), drew equal amounts of suspicion from the state. The cap was first adopted as a symbol of left-leaning Pashtun nationalism by Ghaffar Khan’s Khudai Khidmatgar (KK) in the 1930s.

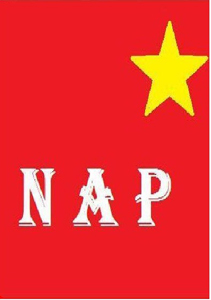

The KK had demanded a separate Pashtun state during the partition of India in 1947. So once the Pashtun-majority area of the NWFP (present-day KP) became part of Pakistan, KK was banned. However, in 1957 it reemerged as a part of the left-wing National Awami Party (NAP). Even though NAP was made up of Pashtun, Sindhi, Baloch and some Bengali nationalist groups, the red cap became popular with its activists and supporters.

The celebrated leftist student and labour leader and one of the founders of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) late Meraj Muhammad Khan once told me that during the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, or when the Soviets became antagonistic towards each other’s idea of socialism, the pro-China members of NAP discarded the red cap and adopted the famous ‘Mao cap’ (baggy green with a red star).

Khan said that during the students’ movement against the Ayub Khan regime in 1968, the police would be more aggressive towards NAP protesters wearing red caps than against students wearing a Mao cap. This was mainly due to the fact that Pakistan was diplomatically closer to China than it was to the Soviet Union.

NAP’s red cap continued to be seen suspiciously, especially when the party was banned by the Bhutto regime in 1975 for being ‘anti-state.’

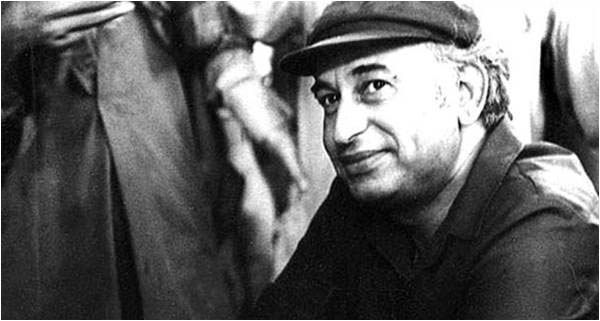

On the other hand, the Mao cap was briefly turned into a populist fashion statement when chairman of the PPP and Pakistan PM ZA Bhutto began wearing it - at least until the collapse of Mao’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China and his demise in 1976.

In 1986 NAP reemerged as ANP. By the late 1980s it had become a mainstream Pashtun nationalist party, but one that had discarded NAP’s more radical nationalist postures. The red cap was retained by ANP, but to the state, it was not symbolizing separatist sentiments anymore.

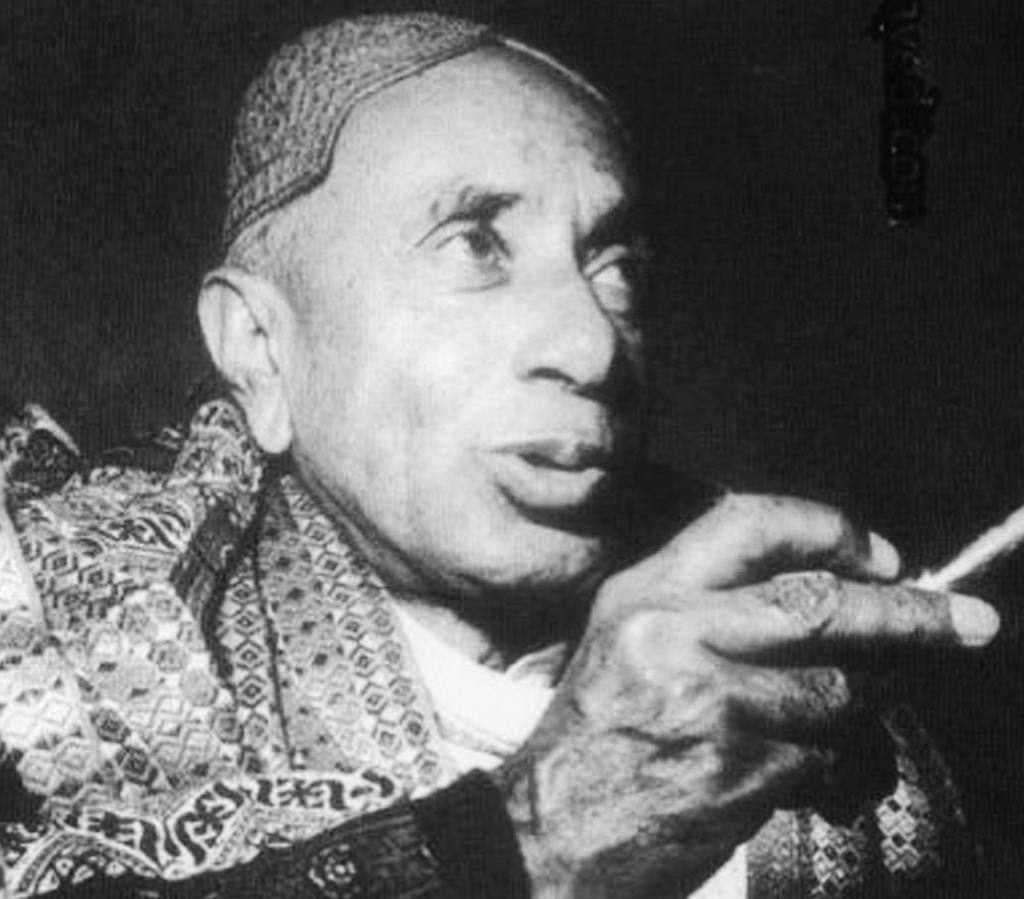

Another cap that began to be seen as a threat by the state was the traditional Sindhi cap. Even though this cap had been part of Sindh’s folk tradition for hundreds of years, it was first politicized by the formidable Sindhi nationalist scholar GM Syed.

After forming the Jeeay Sindh Party (JSP) in 1972, Syed openly declared his desire to separate Sindh from Pakistan. He also asked his followers to always wear the Sindhi cap (and ajrak) to demonstrate their Sindhi identity.

PM Bhutto, who was also a Sindhi, neutralized this by often adorning the Sindhi cap. S Das in his book, Nation Building, Ethnicity and Regional Politics in South Asia, wrote that in 1975 the Bhutto regime organized a ‘Sindh Conference’ in Karachi.

The government made sure to filter out Sindhi nationalists from the event, and one speaker explained the Sindhi cap and ajrak not as symbols of Sindhi separatism, but of Pakistan’s Sufi and mystical heritage.

Indeed, the Bhutto regime had reoriented the meaning behind wearing the Sindhi cap, but after he was executed through a controversial trial by the reactionary Gen Zia dictatorship in 1979, the Sindhi cap became a symbol of protest against the Zia government.

During a major protest movement in Sindh in 1983, not only were anti-Zia Sindhi men and women started to frequently wear the cap, but non-Sindhi youth too began to wear it. I was one of them.

I remember, throughout the Zia regime, young men in Karachi who would venture out in a Sindhi cap would often get stopped and checked by the police. To the cops the cap symbolized Sindhi separatism; but to a majority of young men and women, wearing the Sindhi cap was nothing more than an expression of disgust and defiance towards a reactionary and repressive dictatorship that had executed an elected PM.

However, two decades later, the Sindhi cap began to be celebrated every year during the annual Sindhi Culture Day that is largely organized and endorsed by mainstream organs of the government and the state.

Maybe same will happen to the ‘Pashteen cap?’ Yes, but only if the state realizes that thorny ethnical issues can only be settled through a policy of integration and not elimination. As we have seen, such issues require intelligent responses, not knee-jerk reactions.

Editor's note: Ever since the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement gained power, 'Pashteen Cap' has been in the limelight, with many of the Pashtuns endorsing it. Contrary to the love it gained, there have been a lot of suspicious and knee-jerk reactions given by the state and its security forces, assuming it as some kind of a threat to nation. Having mentioned that, Nadeem Farooq Paracha traces the history of such symbolically celebrated caps which actually gained state's attention overtime.

Recently, supporters of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movemnt (PTM) flooded the social media claiming that security forces in the tribal areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) were arresting anyone wearing the ‘Pashteen cap.’ The cap, also known as the Mazari topi or Mazari cap, is said to have originated hundreds of years ago in the Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif.

It was made famous among young Pashtuns of Pakistan not too long ago by PTM’s 24-year-old leader, Manzoor Pashteen, who can be seen always wearing it.

Pashteen is a fiery orator and activist who has been leading a movement against what he says is the Pakistani state’s neglect of the rights of the Pashtuns and the long-time disfigurement of the Pashtun identity. Pashteen believes that both the state as well as the extremists continue to explain the Pashtun community as being inherently and culturally aggressive.

Truth is, this image of the Pashtun community was originally concocted by the British in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was then willingly adopted by the community itself before the state of Pakistan reoriented it to mean a religiously charged people willing to ‘defend Islam’ through the barrel of the gun.

This image too was largely adopted by many members of the Pashtun community until the community was devastated by the consequent emergence of various reactionary militant groups from within.

Pashteen’s movement today is looking to dispel this identity that has become a cultural burden for the Pashtun. But it is doing this by putting the blame entirely on the state of Pakistan and ignoring the fact that this damaging identity was once willingly assumed by many sections from within his own community.

This is one reason why the state of Pakistan is reacting the way it is against the PTM. So whereas on the one hand the ‘Pashteen cap’ on a young Pashtun’s head symbolizes his or her desire to refigure the community’s identity, on the other hand, to the state of Pakistan, it has begun to symbolize a threat of sorts.

Interestingly, this is not the first time in Pakistan that a cap has been looked at with such suspicion. Once the red cap worn today by the mainstream Pashtun nationalist outfit, the Awami National Party (ANP), drew equal amounts of suspicion from the state. The cap was first adopted as a symbol of left-leaning Pashtun nationalism by Ghaffar Khan’s Khudai Khidmatgar (KK) in the 1930s.

The KK had demanded a separate Pashtun state during the partition of India in 1947. So once the Pashtun-majority area of the NWFP (present-day KP) became part of Pakistan, KK was banned. However, in 1957 it reemerged as a part of the left-wing National Awami Party (NAP). Even though NAP was made up of Pashtun, Sindhi, Baloch and some Bengali nationalist groups, the red cap became popular with its activists and supporters.

The celebrated leftist student and labour leader and one of the founders of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) late Meraj Muhammad Khan once told me that during the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, or when the Soviets became antagonistic towards each other’s idea of socialism, the pro-China members of NAP discarded the red cap and adopted the famous ‘Mao cap’ (baggy green with a red star).

Khan said that during the students’ movement against the Ayub Khan regime in 1968, the police would be more aggressive towards NAP protesters wearing red caps than against students wearing a Mao cap. This was mainly due to the fact that Pakistan was diplomatically closer to China than it was to the Soviet Union.

NAP’s red cap continued to be seen suspiciously, especially when the party was banned by the Bhutto regime in 1975 for being ‘anti-state.’

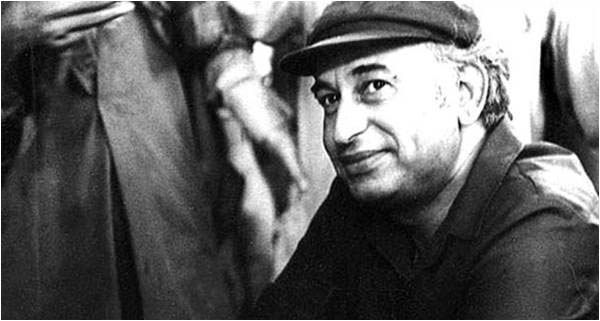

On the other hand, the Mao cap was briefly turned into a populist fashion statement when chairman of the PPP and Pakistan PM ZA Bhutto began wearing it - at least until the collapse of Mao’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China and his demise in 1976.

In 1986 NAP reemerged as ANP. By the late 1980s it had become a mainstream Pashtun nationalist party, but one that had discarded NAP’s more radical nationalist postures. The red cap was retained by ANP, but to the state, it was not symbolizing separatist sentiments anymore.

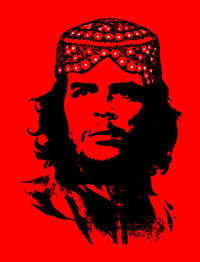

ZAB in his Mao Cap.

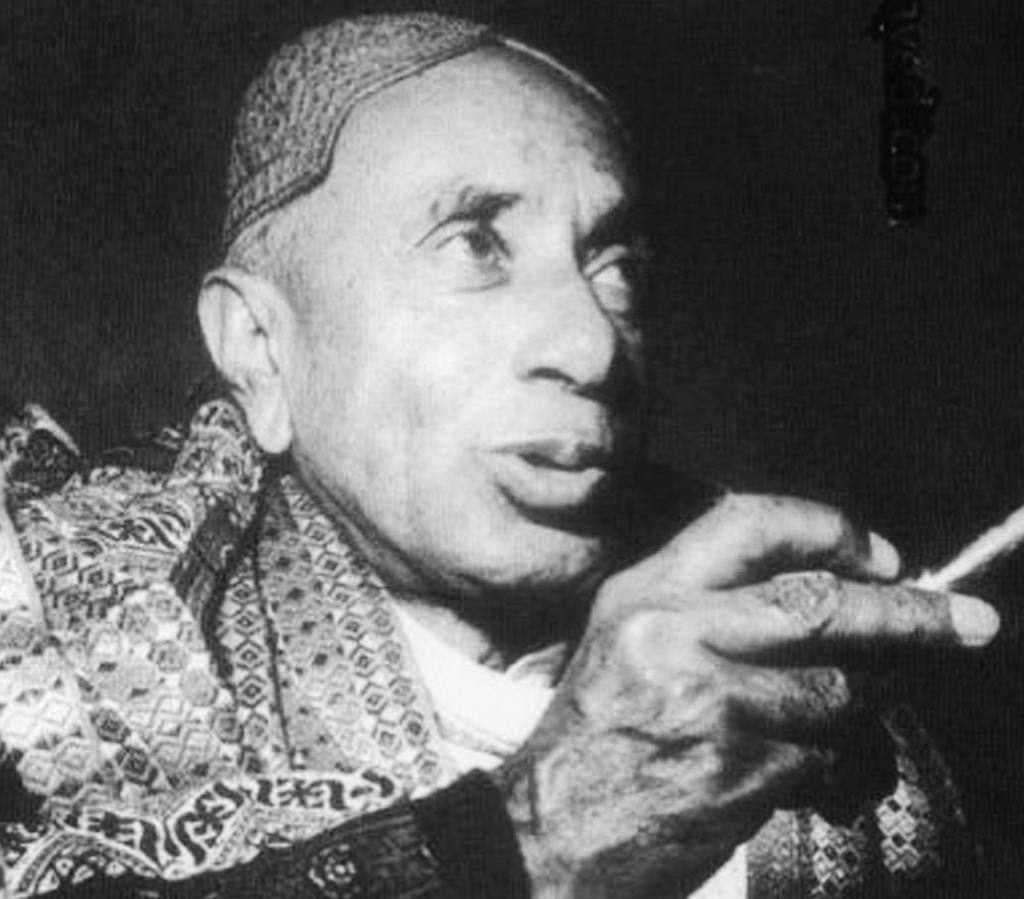

Another cap that began to be seen as a threat by the state was the traditional Sindhi cap. Even though this cap had been part of Sindh’s folk tradition for hundreds of years, it was first politicized by the formidable Sindhi nationalist scholar GM Syed.

After forming the Jeeay Sindh Party (JSP) in 1972, Syed openly declared his desire to separate Sindh from Pakistan. He also asked his followers to always wear the Sindhi cap (and ajrak) to demonstrate their Sindhi identity.

PM Bhutto, who was also a Sindhi, neutralized this by often adorning the Sindhi cap. S Das in his book, Nation Building, Ethnicity and Regional Politics in South Asia, wrote that in 1975 the Bhutto regime organized a ‘Sindh Conference’ in Karachi.

The government made sure to filter out Sindhi nationalists from the event, and one speaker explained the Sindhi cap and ajrak not as symbols of Sindhi separatism, but of Pakistan’s Sufi and mystical heritage.

GM Syed wearing the traditional Sindhi cap. To him the cap symbolized Sindhi separatism.

ZAB promoted the Sindhi ajrak and cap as symbols of Pakistan’s Sufi heritage.

Indeed, the Bhutto regime had reoriented the meaning behind wearing the Sindhi cap, but after he was executed through a controversial trial by the reactionary Gen Zia dictatorship in 1979, the Sindhi cap became a symbol of protest against the Zia government.

During a major protest movement in Sindh in 1983, not only were anti-Zia Sindhi men and women started to frequently wear the cap, but non-Sindhi youth too began to wear it. I was one of them.

I remember, throughout the Zia regime, young men in Karachi who would venture out in a Sindhi cap would often get stopped and checked by the police. To the cops the cap symbolized Sindhi separatism; but to a majority of young men and women, wearing the Sindhi cap was nothing more than an expression of disgust and defiance towards a reactionary and repressive dictatorship that had executed an elected PM.

In the 1980s, the Sindhi cap became a symbol of resistence against the reactionary Zia dictatorship.

However, two decades later, the Sindhi cap began to be celebrated every year during the annual Sindhi Culture Day that is largely organized and endorsed by mainstream organs of the government and the state.

Maybe same will happen to the ‘Pashteen cap?’ Yes, but only if the state realizes that thorny ethnical issues can only be settled through a policy of integration and not elimination. As we have seen, such issues require intelligent responses, not knee-jerk reactions.