British annexed Punjab in 1849 from the Sikh rulers and Lahore became the provincial capital and went through different phases of development. Lahore witnessed the opening of grand railway station in 1862 connecting it with the rest of the India for better and faster transportation of tradable goods. The establishment of British cantonment by transforming historical buildings into offices and constructing new buildings of modern architecture started to change the face of Lahore. Colonizers tried to modify old fashioned architecture but many historical buildings of cultural and religious importance continue to serve as the sites of remembrance of the cultural legacy of Lahore. William Glover in his book Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City rightly said, “When the British occupied Lahore in 1849, they lived in a physical milieu”.

In addition to Lahore’s rich architectural heritage and historical significance, Lahore was also known for its festivals. It was said that the number of festivals celebrated in Lahore exceeded the number of days in a year. Some of the major festivals locally known as ‘Melas’ included Bahadarkali mela, Chiragan mela, Kadmon ka mela and Mela Data Gang Baksh, which were celebrated at specific sites and people used to travel to those sites in order to attend them. In addition to these religious and Sufi melas there were festivals which were more cultural and widely celebrated all over Punjab, like Basant, Teej, Tayan and Wasakhi and were mainly associated to seasons like the arrival of spring season and other regional causes like crop cutting and harvest. These festivals included temporary markets and exhibitions where local artisans showcased their work and skills. Therefore, these festivals were the source of promotion, revival of arts, remembrance of past events and economic activity for inhabitants of the surrounding regions.

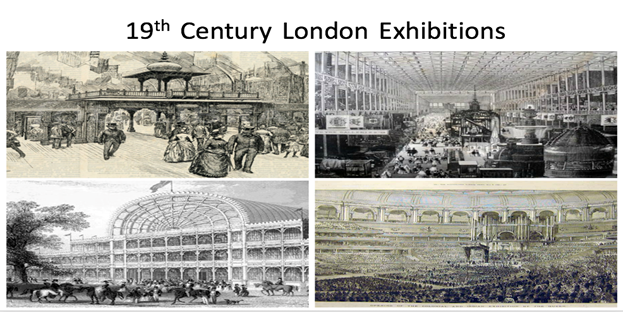

The British project of modernization of Lahore also brought the colonial exhibitions to Lahore. Colonial exhibitions were an important part of British empire. The great age of exhibitions sprouted out of the industrial and technological advances of the west. Britain used these exhibitions to showcase their production potential and progress. Britain represented its colonies in these exhibitions and introduced them to each other and to the rest of world. The great exhibitions of Britain were extremely popular and well attended and made the whole world look up to Britain as the epoch of development, modernity and civilization. When the British decided to conduct exhibitions in Lahore they also intended to achieve same popularity, attendance and dedication for their exhibitions from the local Punjabis. British aims were bigger and their goals were not regional or national but international.

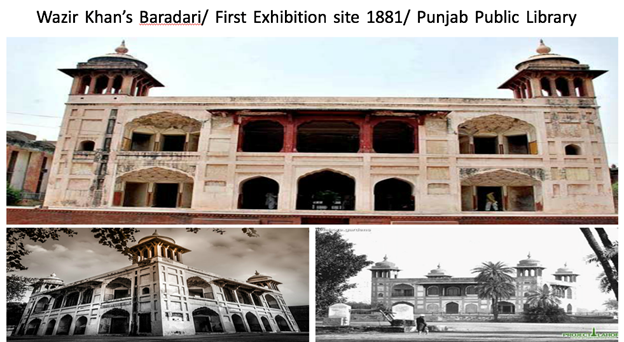

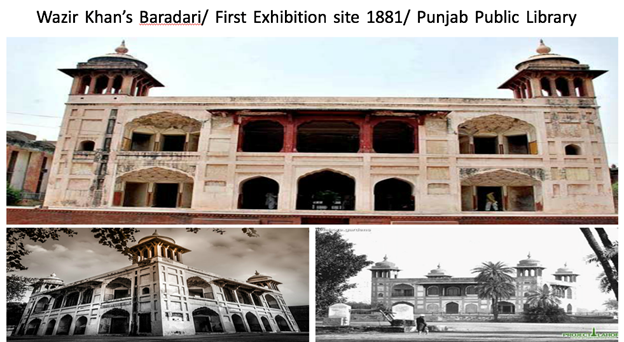

In order to conduct the first exhibition in 1881, the selection of exhibition building was a cumbersome and tricky task. There was no specially designed building or place available for this purpose as the concept itself was new to India and this exhibition was the first of its own kind in Lahore. An existing building had to be selected for the exhibition with the agreement of Punjab’s government and British administrative authorities therefore “Wazir Khan’s Baradari” was selected.

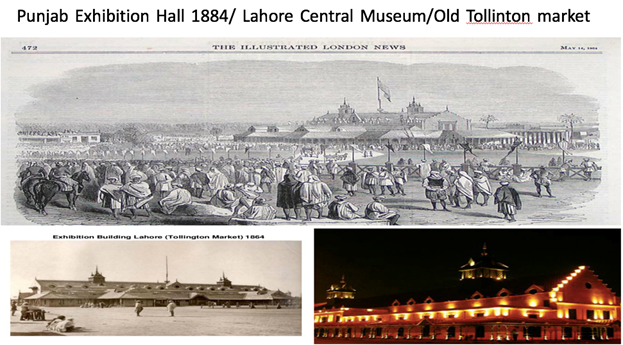

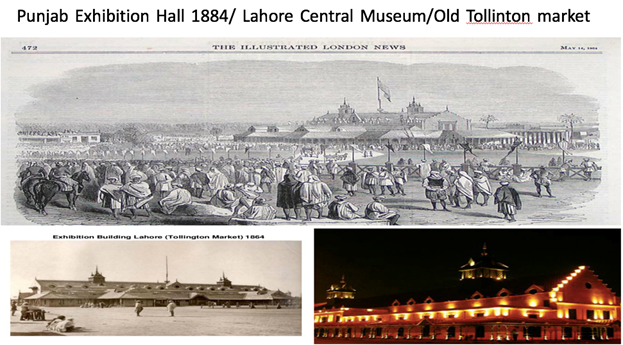

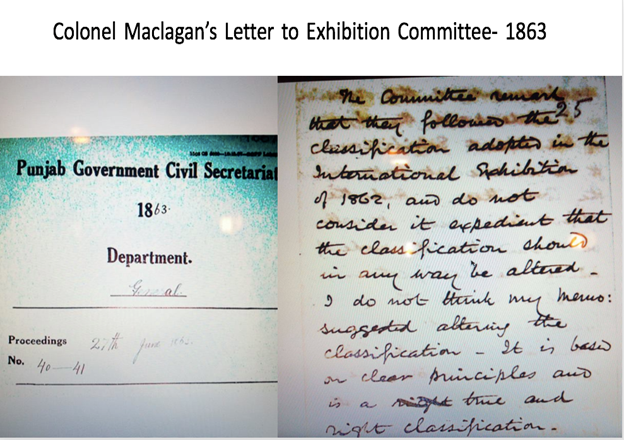

As the years passed and as the number of people participating and visiting these exhibitions increased, the need for a separate, bigger and purposefully built structure was felt and a temporary building was constructed on the Mall in 1864 that housed one of the most stupendous exhibitions of Punjab under the British Raj in the same year. This building served as a central museum for the next twenty-six years due to financial constrains in constructing a separate building for the museum. Availability of funds remained a constant problem during the construction of this exhibition building which we can see through the correspondence between the Punjab exhibition committee 1863-4, Government of Punjab and especially Colonel Maclagan who was the British officer taking care of all the exhibition arrangements.

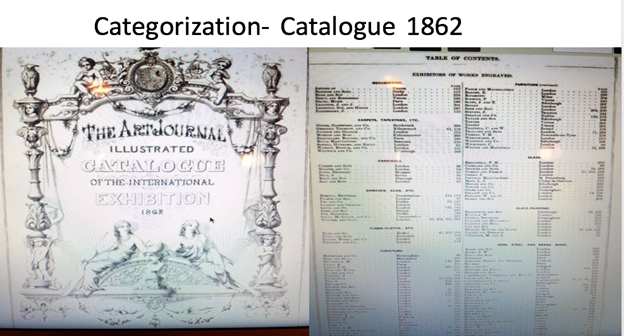

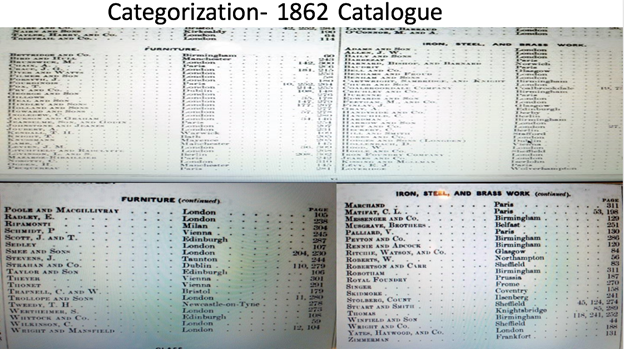

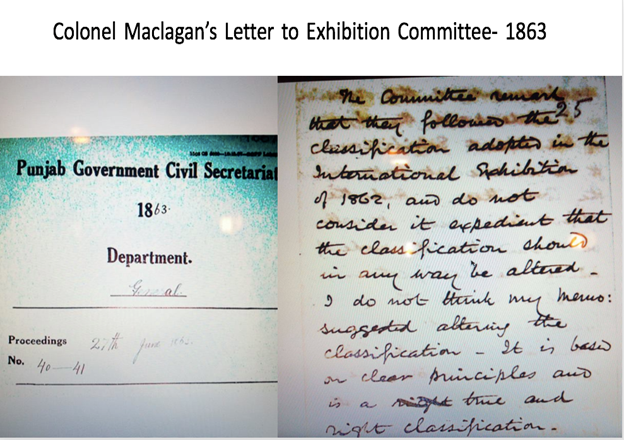

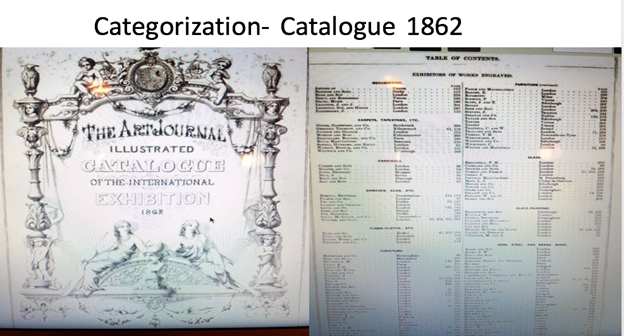

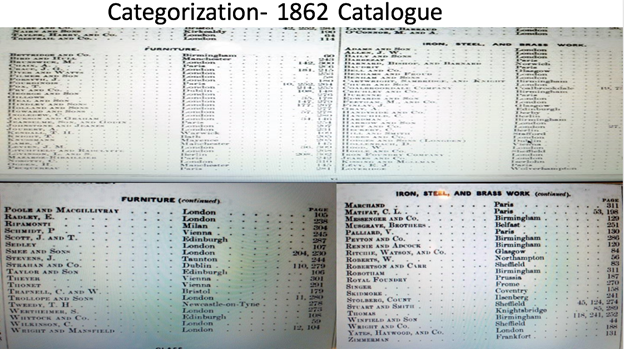

The catalogues and the classification of the products exhibited in the exhibition strictly followed the catalogues of London exhibitions as perfect templates. It is fascinating to go through the catalogue of 1881-2 exhibition and notice how rich they were in their range and extent. The catalogued products included jewelry, clothes, utensils, ornaments, accessories, paper products, natural products, animal products, food items, ‘traditional’ weapons and raw material, all of these things were catalogued under these eleven categories; objects contributed to loan, embroideries, fancy needle work created by women, leather, pottery, glass, wood work, design, tea, miscellaneous and supplementary categories. However, the catalogue of “colonial and Indian exhibition 1886”, which is a special catalogue of exhibits by the government of India and private exhibitors, appears to be much more systematic, extensive, detailed, descriptive and informative than the catalogue of previous exhibitions. The classification for selection was also a replica of classification adopted for London exhibition of 1862 (also called London international) about which Colonel Maclagan said “It is based on clear principles and thus right and true”.

The Lahore exhibition committee and Colonel Maclagan both seemed to be overly concerned by these classifications to be followed for the 1863-4 exhibition. Such course of action required committee to be conscious of the extent of range of articles from which the exhibits could be selected. However, while the committee saw this consciousness as a scope expanding tool, Maclagan saw it as a limitation. Committee encouraged to include more and more Indian products by expanding the scope of already diverse categories of London exhibitions which means not to be really strict about what could be included in which category. On the other hand, Colonel Maclagan insisted on inflexible implementation of London catalogue classification by selecting only those products that match the products of London exhibitions in taste and quality. So Maclagan’s choice was quiet endemic to tradeable goods.

Although the first exhibition of 1881-82 was reported to be overcrowded and natives’ response was overwhelming as a lot of people participated and visited, with the passage of time this excitement curve went down as people found these exhibitions unattractive due to many reasons. The fact that natives had to pay an admission fee in order to visit these exhibitions and to see their own products, reflects that there were many reasons for exhibitions to grow less popular with time.

In addition to Lahore’s rich architectural heritage and historical significance, Lahore was also known for its festivals. It was said that the number of festivals celebrated in Lahore exceeded the number of days in a year. Some of the major festivals locally known as ‘Melas’ included Bahadarkali mela, Chiragan mela, Kadmon ka mela and Mela Data Gang Baksh, which were celebrated at specific sites and people used to travel to those sites in order to attend them. In addition to these religious and Sufi melas there were festivals which were more cultural and widely celebrated all over Punjab, like Basant, Teej, Tayan and Wasakhi and were mainly associated to seasons like the arrival of spring season and other regional causes like crop cutting and harvest. These festivals included temporary markets and exhibitions where local artisans showcased their work and skills. Therefore, these festivals were the source of promotion, revival of arts, remembrance of past events and economic activity for inhabitants of the surrounding regions.

The British project of modernization of Lahore also brought the colonial exhibitions to Lahore. Colonial exhibitions were an important part of British empire. The great age of exhibitions sprouted out of the industrial and technological advances of the west. Britain used these exhibitions to showcase their production potential and progress. Britain represented its colonies in these exhibitions and introduced them to each other and to the rest of world. The great exhibitions of Britain were extremely popular and well attended and made the whole world look up to Britain as the epoch of development, modernity and civilization. When the British decided to conduct exhibitions in Lahore they also intended to achieve same popularity, attendance and dedication for their exhibitions from the local Punjabis. British aims were bigger and their goals were not regional or national but international.

In order to conduct the first exhibition in 1881, the selection of exhibition building was a cumbersome and tricky task. There was no specially designed building or place available for this purpose as the concept itself was new to India and this exhibition was the first of its own kind in Lahore. An existing building had to be selected for the exhibition with the agreement of Punjab’s government and British administrative authorities therefore “Wazir Khan’s Baradari” was selected.

As the years passed and as the number of people participating and visiting these exhibitions increased, the need for a separate, bigger and purposefully built structure was felt and a temporary building was constructed on the Mall in 1864 that housed one of the most stupendous exhibitions of Punjab under the British Raj in the same year. This building served as a central museum for the next twenty-six years due to financial constrains in constructing a separate building for the museum. Availability of funds remained a constant problem during the construction of this exhibition building which we can see through the correspondence between the Punjab exhibition committee 1863-4, Government of Punjab and especially Colonel Maclagan who was the British officer taking care of all the exhibition arrangements.

The catalogues and the classification of the products exhibited in the exhibition strictly followed the catalogues of London exhibitions as perfect templates. It is fascinating to go through the catalogue of 1881-2 exhibition and notice how rich they were in their range and extent. The catalogued products included jewelry, clothes, utensils, ornaments, accessories, paper products, natural products, animal products, food items, ‘traditional’ weapons and raw material, all of these things were catalogued under these eleven categories; objects contributed to loan, embroideries, fancy needle work created by women, leather, pottery, glass, wood work, design, tea, miscellaneous and supplementary categories. However, the catalogue of “colonial and Indian exhibition 1886”, which is a special catalogue of exhibits by the government of India and private exhibitors, appears to be much more systematic, extensive, detailed, descriptive and informative than the catalogue of previous exhibitions. The classification for selection was also a replica of classification adopted for London exhibition of 1862 (also called London international) about which Colonel Maclagan said “It is based on clear principles and thus right and true”.

The Lahore exhibition committee and Colonel Maclagan both seemed to be overly concerned by these classifications to be followed for the 1863-4 exhibition. Such course of action required committee to be conscious of the extent of range of articles from which the exhibits could be selected. However, while the committee saw this consciousness as a scope expanding tool, Maclagan saw it as a limitation. Committee encouraged to include more and more Indian products by expanding the scope of already diverse categories of London exhibitions which means not to be really strict about what could be included in which category. On the other hand, Colonel Maclagan insisted on inflexible implementation of London catalogue classification by selecting only those products that match the products of London exhibitions in taste and quality. So Maclagan’s choice was quiet endemic to tradeable goods.

Although the first exhibition of 1881-82 was reported to be overcrowded and natives’ response was overwhelming as a lot of people participated and visited, with the passage of time this excitement curve went down as people found these exhibitions unattractive due to many reasons. The fact that natives had to pay an admission fee in order to visit these exhibitions and to see their own products, reflects that there were many reasons for exhibitions to grow less popular with time.